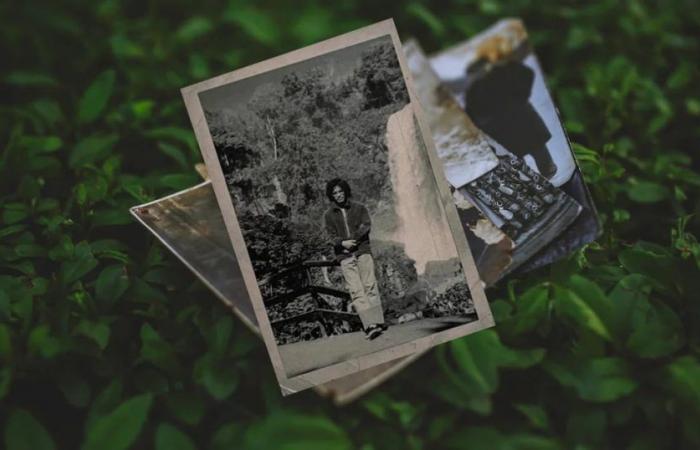

White background and a travel postcard in the center. A man of large build, indefinite age—20 years?, 30?, 40?, how many?—, prominent hair, swollen cheekbones, and cataracts in the background. He seems to be Brazil. Above, with pen, “The Poems of Boy Fracassa.” It is a striking name: funny and at the same time haughty. Inside the book, indeed, poems. And a few more things: Martin Caamano, who translated the book from Portuguese, included a “Translator’s Note”; the poet Fabian Casas he dedicates an epilogue to it; and Adrian Dargelospoet, leader of Babasonics, wrote the back cover, whose oddity is that it extends to the flap. Who is that burly gentleman who poses very calmly and who writes things like “my muscles are proportional to my desperation” and “the world is full of poorly distributed pain”? In principle, a secret that has just been revealed: The poems of Boy Fracassa It is the latest novelty from Ediciones Nebliplatada.

Let’s continue going through the book. On the back of this thin white object, Dárgelos—who, after a long musical career still far from abating, published his first collection of poems in 2019, Shadow offerand this year, the second: Nobody’s voice— tells how he came to his poetry. He talks about Lanús at the end of the eighties. He remembers a group of boys, all between adolescence and adulthood, all older than him, who went on vacation to Brazil and got caught for smoking marijuana and who the police let go in exchange for all the money they had. One of them, Carlitos Vicio, wanted to stay. “They didn’t hear from him until six months later. He came back changed, speaking very fluent Portuguese (…) The truth is that Carlitos was different,” says Dárgelos who, he claims, met him on the street, told him his version of the events, and “gave him a small book and groped that he brought with him. That book was The Sertón of Boy Fracassa”.

“The first time I heard the name Boy Fracassa It was in 2018 during a scholarship for Latin American translators in Switzerland.” This is how the prologue by Caamaño begins, who has two published novels (pale reflection and Oslo), eight discs with Rosebush and a long love affair with Brazilian literature, of which he is a specialist. This “Translator’s Note” begins with the anecdote of a Brazilian who there, in Switzerland, begins to talk to him about Fracassa, sends him verses on WhatsApp and sows the seed of obsession. “Years later Fabián Casas sent me a long audio telling me that he had the messianic idea of publishing The Sertón in Argentina and asked me to take care of the translation,” he says, and continues: “Translating poetry is not an easy task. Translate to Fracassa much less. Already the title, an explicit reference to Euclides da Cunha and his Os Sertõesone of the foundational books of Brazilian literature, anticipates the complexities that I had to face.”

Fabian Casas found the book in the library that the tennis player Gaston Gaudio he has in his house. With him, she says, she lived in “a very unstable moment” in his life. In turn, Gaudio received that book from another tennis player, the Brazilian Guga Kuerten, also a tennis player, which in turn was given to him by his cousin Clarice, “an intrepid traveler.” The original of The Sertón, Fracassa’s manuscript, is “a notebook with several poems that is abandoned in a backpack torn to pieces on the side of a hut in a corner of the jungle,” the poet and writer says in the epilogue, the postface. Then, the future made it reach more and more readers, until an editor had the time, the money and the desire to publish it. And now, as we understand it, Casas proposes it, Caamaño translates it, Dárgelos writes the back cover and the publisher Nebliplateada realizes the dream of these poems reaching Spanish-speaking readers.

The poems have no titles, each one occupies a page, and they read like linked scenes and thoughts. The first, the one that opens, is the following: “The little girl in the heart of the sun / woke up bigger / the whole tribe surrounded her / so that she would not stain the river / with her blood / I cried with emotion” . The second talks about a man, the Godfather Alfredo, who gives him profound advice: “Look at your soul/ full of misfortunes/ and look for a place/ for beautiful adventures.” The third, which tells about the arrival of “an original person” to the colony and about a “big headache,” seems to be a reference to The expert of Juan José Saer; although it could be a coincidence. With a jungle atmosphere, where the mystical opens up as a higher stage than the mundane of civilization, the poems draw names, scenes, objects, details and traffic totalizing ideas: “This poem is about the blank mind. / Trying to say that thought is pain.”

“The history of poetry could be a biography of breathing. Something like that must have felt Boy Fracassa when he decided to leave – from one day to the next – Colonia 5000 where he lived in a community in the Amazon and go into the jungle to meditate and try – according to the words reported by his friend Horacio Tomasello with whom he shared a hut in the colony – learning to live off the air,” he says in the epilogue. Casas, where he reveals more issues about this enigmatic character. Then he wonders why he wrote in Portuguese and not in his native English, and the answer he finds is the one he receives from Tomasello: “He said that genius lived in that new language, something that was impossible for it to emerge in his assimilated native language.” to ‘common sense’”. That genius of which he speaks is “something that nests inside all people, giving a variant to the aristocratic idea of genius that he had, for example, Nietzsche”.

“All I want/is power/mystery/and the hammer of the gods,” he writes. He also refers to someone who “went to meditate at the bottom of the forest / but there was no forest,” of someone who “went to meditate where no one can meditate.” Does he talk about himself? “Dear Jacqueline / I apologize / for that time I broke the washing machine / that your parents gave you / for all the times I changed my personality,” reads this epistolary poem to her sister. Then he gets lost watching some red ants and talks to Jacqueline again, about him, about her, about a change, about the future: “but soon/ I know/ I will be great again.” There is also optimism in Boy Fracassa: “I guess the humans will win anyway.” She doesn’t affirm it, she assumes it. There is more doubt than there is certainty, but she leans towards that possibility: there is hope. Who will the humans beat? To technology? To the hidden forces of nature? That’s another secret that Boy Fracassa took with him wherever he wants to be.

Another verse: “I dedicated my life to something that has no meaning.” Perhaps that explains this poem: “What a stupid question/ is what book would you take to a desert island/ to a desert island/ would I take/ a revolver/ to shoot myself/ books are to be read among people.” What does Fracassa do in Brazil, in the colony first, then in the jungle? What is he looking for, what is he escaping from, is there the idea of returning, where? According to Casas, “he had to leave the United States due to McCarthyist persecution,” then he arrived in Uruguay, to a commune of Tupamaros, fell in love with a certain Victoria—the book is dedicated to her: “To Victory, ever”—and traveled across the continent until reaching Brazil where, it seems, he finds something important: silence? Tranquility? to himself? “He began to meditate one day in the lotus position, inside an immense tree that served as shelter. He was like this for many days without consuming water or food.” Ten days in total, then he disappeared: he vanished forever.