By María José Rey |

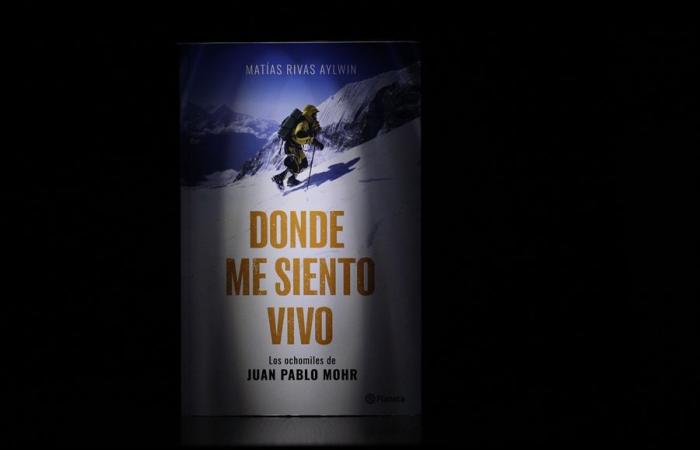

Santiago de Chile, June 20 (EFE).- Mountaineers see themselves as “conquerors of the useless,” warns the writer Matías Rivas in an interview with EFE, about his book ‘Where I feel alive’ (Planeta, 2024), a profile of the Chilean climber Juan Pablo Mohr, who died in 2021 on K2, attempting his sixth summit above 8,000 meters in the Himalayas.

“The place where he died and the circumstances that led to that outcome are quite clear. That his death is a mystery adds greater magnetism to the story,” comments the 31-year-old Chilean journalist, who is also a climber.

The author explains that among mountaineers it is very common to say that death can come to you anywhere. Therefore, for Mohr that was not a reason to stop doing what he loved.

A work based on the immersion of Matías Rivas

“Knowing what his last thoughts were is really a mystery,” says Rivas, because Mohr only wrote logs. Through research and interviews with family, friends and climbers who knew him, the writer understood that inside him “a kind of acceptance of his destiny began to appear.”

About the expedition to the ‘wild mountain’, the second highest in the world and never done in winter, “a documentary will be released soon on some platform,” Rivas notes. Four other climbers also died there that year, including Mohr’s partner Sergi Mingote – weeks before – and the other two who made the final ascent with the Chilean.

“I knew that he climbed without oxygen, but I didn’t see in him that romanticism of other mountaineers,” acknowledges the author, who understood the magnitude of that project, which encouraged him not to continue ignoring his story.

“I felt very curious to understand it, because I saw very clearly that it was not for money or fame. Nobody does K2 for such frivolous reasons, because it is very likely that you will not come back and there is a lot of suffering involved,” he comments.

Matías Rivas manages to explain mountaineering and its more technical terms with a simple narration through the story he wanted to tell and, thus, contribute to the literature on the subject, which is scarce in Chile: “Two thirds of the territory are mountains and I could never find a mountain book in bookstores.”

The position in which they found Mohr’s body shows that he was descending. Did he reach the top? “It is said that the true summit is when you arrive safely at base camp, or even more so, at your house. In that sense they did not succeed,” he says of the three climbers who were buried there.

“The most important thing in this story is the moment in which they are making the decisions to go or not to the summit. I think it is very difficult to obtain the truth or something that comes close to it,” he points out. And he adds: “Mountaineers say that the mountain speaks, and that K2 was talking a lot on that expedition.”

The importance of mountaineering for Mohr

A group of Nepalis led by Nirmal Purja announced that they had conquered K2 first, that winter without artificial oxygen, but they reserved key details. “My conclusion is that the Nepalese preferred that no one else reach the summit that season,” he points out.

“Mountain literature teaches that mountaineers are not necessarily noble beings and that they always tell the truth. Mountaineering is full of lies, deceit and betrayal,” he points out.

Mohr was virtually immune to altitude sickness. Very few mountaineers climb Everest without supplemental oxygen, he says. “When you have a gift, something that sets you apart so much from the rest, it’s a little irresistible to want to use it,” he says.

Rivas describes an independent Mohr, who said that “if he was not in the hills he felt incomplete,” but who also tried to bring the mountains closer to his three children and to the people with projects such as the Fundación Deporte Libre, the Torres de los Silos, the shelters of ‘The 16 of Chile’.

“I didn’t have a pressure to want to honor him, I wanted it to be fair,” he says.

A life facing fear over and over again “is like a fire in the blood,” says Matías Rivas. And he adds: “What you experience is a very deep, very broad feeling of freedom. “The summits are spaces of freedom.” A conquest of oneself.