At the end of January 1957, the newspaper The nation announced: “In the coming days, possibly next week, the demolition of the Tabernacle Chapel will begin, for the expansion of Second Avenue.

“The Metropolitan Council, which manages all the assets of the Costa Rican Catholic Church, has been in agreement with this demolition, and has already taken the necessary measures in this regard.” A few weeks later, in the same newspaper, journalist Joaquín Vargas Coto commented:

“The little temple of the Tabernacle, at the bottom of the small north garden of the Metropolitan Cathedral, is condemned to death. The sentence has been signed by the greedy urgencies of commerce and the needs of increasingly intense vehicle traffic” (This is the house of God and the door to heaven).

The Tabernacle chapel seen from 2nd Avenue, in the mid-1960s. (Photograph by Manuel Gómez Miralles (Andrés Fernández for LN))

Chapel and parish

Costa Rica was established as a Republic, a sovereign and independent nation, in August 1848; and by February 1850, it was recognized by the Holy See.

But, as until then local religious issues depended on the bishopric of León, Nicaragua; In parallel with the request for recognition from the Vatican, the request had also been presented for the erection of the bishopric of Costa Rica, a desire that dated back to the time of the conquest.

Thus, on February 28, 1850, Pope Pius IX issued the bull Chistianae Religionis Auctor, erecting the new diocese based in San José. Almost immediately, both news were communicated to our government; to which President Juan Rafael Mora replied, in his Message to Congress on May 1:

“Pleasant and satisfactory it must be for the Republic that the Supreme Pontiff has deigned to erect it into a new diocese. This fortunate event perfects our political independence, provides for the needs of the Church and favors our clergy, deserving of some reward for their piety, zeal and patriotism.”

The “faust event”, however, brought with it a drawback: the Josephine parish building, it was evident, was not related to the cathedral dignity that, according to the bull, it would hold from now on. Furthermore, there was the question of where the capital’s parish would be housed, once its temple became a cathedral.

READ MORE: The Yellow House, a palace for peace

To make matters worse, the earthquake of March 18, 1851 had worsened the poor condition of the building. For this reason, according to Monsignor Sanabria:

“After a visual inspection carried out by Mora on August 6 [de ese año]it was agreed to build the Cathedral from its foundations, also resolving that a church be built first, that of the Sagrario, to the north of the Cathedral, to house the parish and the chapter in the meantime” (Anselmo Llorente y Lafuente. First bishop of Costa Rica).

Such ambitious plans, however, could not be realized immediately or completely, and would take years to come to fruition. Meanwhile, our first bishop, Monsignor Anselmo Llorente, arrived in the country in December 1851; and he took office from him in February of the following year.

From then on, as could be expected, the dual status of the main Josephine temple – parish and cathedral at the same time – did not take long to cause friction and displeasure between the parish priest and the capitulars or members of the ecclesiastical chapter. The construction of an adjoining chapel then became equally or more urgent.

A neoclassical temple

The construction plans – for which 204 pesos were paid – were commissioned from the Prussian engineer-architect Franz Kurtze Krumbhaar (1820-1868), and were ready at the end of February 1855. Then the bishop decreed to begin the construction of the chapel of the Sagrario, a work for which President Mora himself donated the sum of 4,000 pesos from his own pocket.

The Tabernacle chapel in 1871, during the episcopate of Monsignor Anselmo Llorente y Lafuente, first bishop of Costa Rica. (Photograph by Otto Siemon (Andrés Fernández for LN.))

During the first half of the 1850s, mainly in the capital’s public works, the colonial construction system based mainly on earth and wood had been replaced by the use of more durable materials, such as stone and brick. , giving shape to an aesthetic code that represented the ideals of the new Republic.

It was the academic neoclassical architectural language, that is, that of Greco-Roman references, advocated by the European academies of Fine Arts. For that reason, the Mora Theater, the University of Santo Tomás and the National Palace were neoclassical here; and neoclassical would also be the Tabernacle or chapel of the Blessed Sacrament.

Kurtze, not in vain, was one of the introducers of that architecture in the country; So he designed a simple temple with a quasi-rectangular plan, which internally measured eight and a half by seventeen meters. Its doorway protruded slightly to the sides, and the semicircular arch door had two pilasters or false columns of Tuscan order on each side; and it was crowned by a triangular pediment with acroters at the ends, and on them, a type of amphorae.

On each side wall, whose rear ends were slightly octagonal, there were four windows also with a semicircular arch, which were flanked by pilasters of the same Tuscan order. As a cornice of the building, a perimeter parapet that concealed the semi-vaulted galvanized steel roof was topped at its rear ends by pedestals, again with amphorae.

Apart from the chapel itself, its sacristy was also built then, which would be immediately behind; as well as a pavilion from north to south that connected both with the Cathedral and housed the offices of the Chapter. The building, of modest neoclassical appearance in turn, formed an “L” with its cloistered corridors and a garden in the middle.

In the construction of such works, in addition to Kurtze as responsible for the design, the master carpenter Manuel Conejo and – eventually – the bricklayer Tomás Estrada participated as builders, Mr. Joaquín Alvarado as inspector of the work, and the engineer Mariano Montealegre in the direction. technique.

The parishioners of Joseph and the nearby regions were urged to contribute by transporting from Pavas the stone necessary for the construction, as well as the lime that would be used together with it to make the limestone for the foundations and walls.

Demolition and reconstruction

Construction work was suspended during the National Campaign and the cholera plague. But since its completion, in 1866, the Tabernacle was the headquarters of the Josephine priesthood, which functioned there until 1881; when Monsignor Thiel divided the parish between the temples of El Carmen and La Merced. During all those years, the chapel was the site of the capital’s weddings and baptisms, funerals and services for the dead.

In 1901, the artist Andrés Steiner Valentini decorated the walls of its only nave with an eclectic decoration, in accordance with what he himself had given to the Cathedral shortly before. In 1937, under the direction of Monsignor Enrique Kern, the chapel was completely restored; and it was then that it was given its eight colorful stained glass windows.

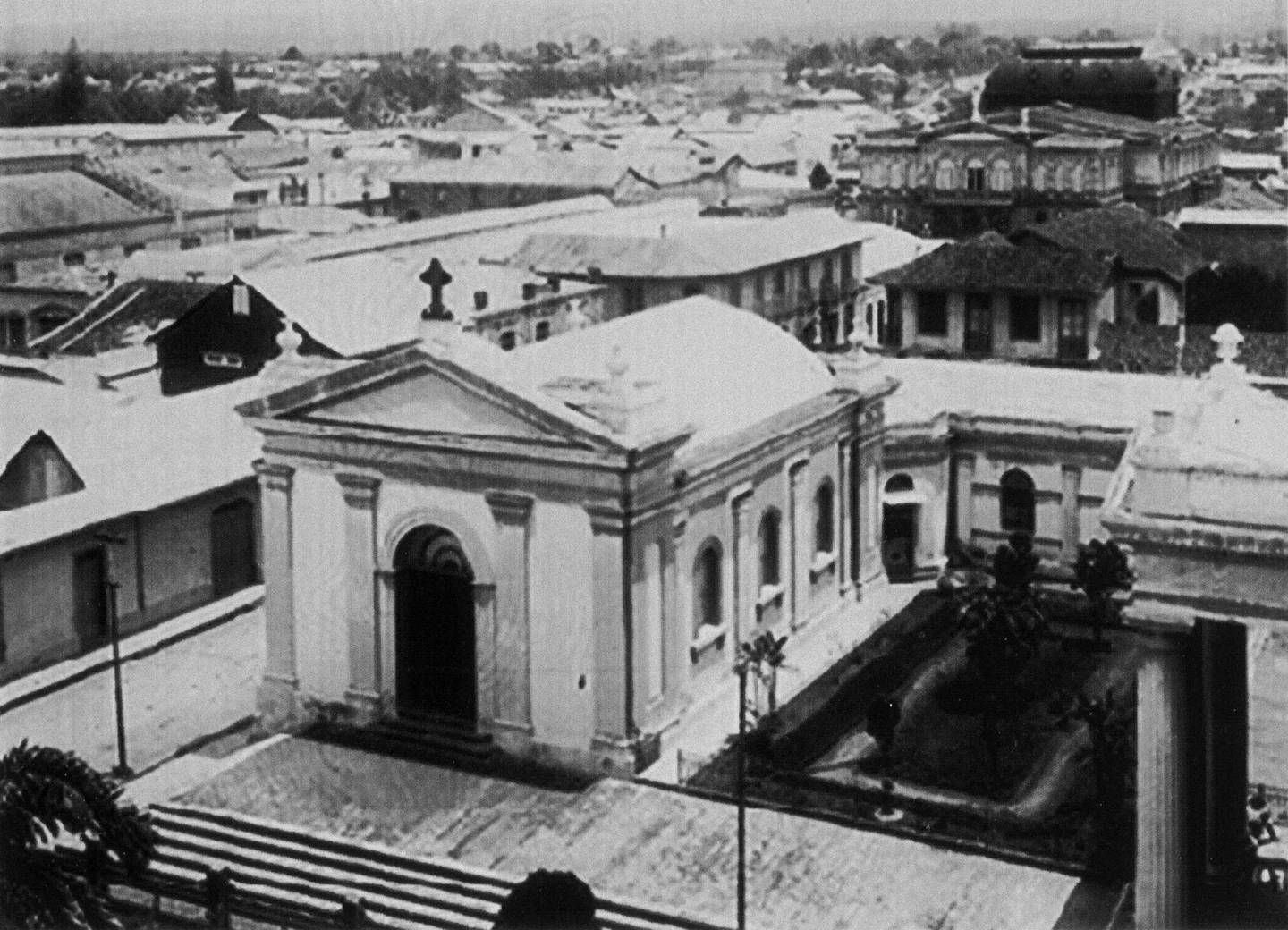

The Tabernacle chapel seen from the cornice of the Metropolitan Cathedral, around 1920. In the background you can see the National Theater. (Photograph by Manuel Gómez Miralles (Andrés Fernández for LN))

However, twenty years later, the news broke among the Josephites: their old and beloved chapel would be demolished to expand 2nd Avenue. This expansion had begun in 1954 with the mutilation north of the Central Park, when talks had also begun with the Church to end the temple.

Thus, in the first half of 1958, a strong controversy broke out in the main newspapers with positions both in favor and against the measure. But Monsignor Óscar José Trejos, secretary of the archbishop, declared that: “The Tabernacle is not a historical relic (…). Consequently, the Church will transfer that part to the Municipality when appropriate.”

But, in June of that year, when everything seemed lost, to temporize –palanganate We Ticos call that – the capital’s Municipality revoked the demolition agreement, and left the issue to the discretion of the next administration.

2nd Avenue between Central and 1st streets, however, was still narrow. So fourteen years later, despite being the oldest temple in the capital, its demolition finally began in May 1972; which lasted until September of the same year.

The Catholic Church – which received one and a half million colones for the land – announced that the chapel would be rebuilt several meters to the south; as indeed happened in 1975. Built of reinforced concrete, the replica is almost exact and was designed by architect Hernán Arguedas Salas, from the company Consultécnica.

In it, the old stained glass windows and the iron and marble balustrade of the presbytery were used, and the painting on the walls was reproduced. Its interior, as appropriate, was sumptuously replicated; although the mosaic brick floor was replaced by terrazzo and the choir and organ disappeared.

Since April 1976, when it was inaugurated, and despite being a “false history,” the new chapel of the Sagrario has continued to be the peaceful corner of the capital of faith and meditation that the chronicler Vargas Coto evoked yesterday. For this reason, it still fully fulfills its spiritual function in our troubled capital today.

The Sagrario chapel is on the north side of the Metropolitan Cathedral, in San José. It is a replica of the original temple, which was demolished to make way for the expansion of Second Avenue. (Alonso Tenorio)