In 1993, in an exhibition of the beneficiaries with the Scholarship of Young Creators of Fonca, the Rusomexican artist Iulia Akhmadeeva (Krasnodar, 1971) saw an example of Mexican contemporary graphic art that he did not know in her student stage in the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). There, rather, he had studied the popular graphics workshop, which, although “extraordinary”, is a work with “social support”, as the official plastic arts in her native country, which the young woman studied in the 80s and 90s of the last century.

That sample surprised him “the ease of experiencing, breaking and extending borders” for aesthetic purposes. It was something that he noticed “much more in the graph than in painting and sculpture”, which seemed “more backward arts regarding their development. I liked this a lot from here. I said: ‘I must be here, learn and do something.’”

Altered territories It is Akhmadeva’s first individual exhibition in a museum in Mexico City. It brings together the production of two work lustra that covers 43 pieces, from graphic series-lithography, siligraphy, colotipia and algiagraph-and notes, to editions of artist, art-object, collage and high temperature ceramic intervened, a new aspect of its production. In them, the exhibitor reflects on issues such as memory, family, migration, identity and transformation of the spaces that are inhabited.

With three decades in Mexico, Akhmadeva affirms that “we are all migrants”, an assertion that leads the exhibition. “In the course of life we move from one side to another. Apart from a few belongings, we carry our memoirs, in our mind, such as symbolic and nostalgic memories, and in objects such as family photographs, archives or letters, because that defines us, and tells us about our ancestors, where they lived, what they did, how their lives were.”

Akhmadeeva was born in the south, “between Georgia and Ukraine”, from a country, as he usually says, that there is no longer: the USSR. In his family, women predominated, since he does not remember the presence of men. Listening to the tales of the maternal grandmother about the war, in which her two grandparents fought, fed her graphic work.

At 18 he went to Moscow to study at the Russian State Academy of Plastic Arts, at the VI Surikov Institute, specializing in graphic art and easel. There she met her Mexican husband, with whom she married in 1993. Her daughter was born in Mexico in 1994. A year after teaching drawing classes at the Ibero -American University, the exhibitor contemplated to occupy subjects at the Popular Faculty of Fine Arts of the Michoacana University of San Nicolás de Hidalgo, in Morelia, where she has resulted in 23 years.

According to Akhmadeva, graphic art in Mexico continues in motion, both in its “urban” facet, and in the expansion of its concepts and experimentation with supports. He is interested in trying new technologies, such as “laser cutting and third dimension print”, without leaving behind the issue of memory, his and that of others.

“Currently, I work with Mexican migrants. This issue was in my plans before Trump declared the mass deportations of Mexican migrants. That is, connect the memory of my experiences with that of other people to interpret and make them visible by taking them to the public and the museum spaces.”

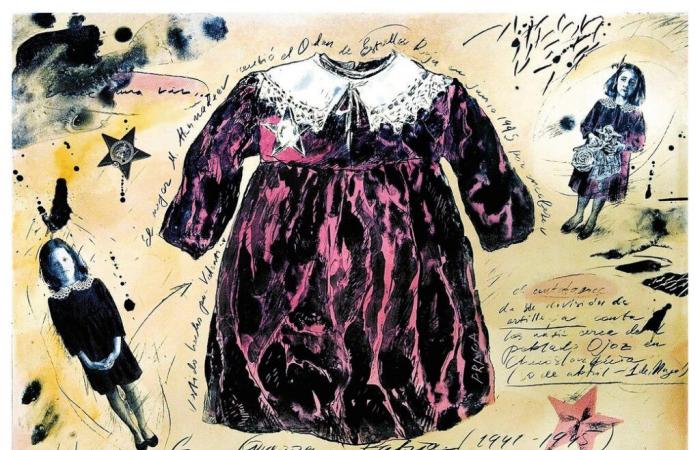

The sample includes a very particular piece by way of the assembly in art-object that is also reproduced graphically. Contained memory II It includes a small dress made with a velvet fabric that her paternal grandfather brought from Czechoslovakia in 1945, and her Ukraine grandmother gave the artist on her wedding day. In 1999, his mother made him a dress for the eldest daughter of Akhmadeeva. It is complemented with a crochet neck intervened with family portraits in lithography, made by its grandmother especially for Ioulia, girl, and the peace pigeons in Ceramic Origami and paper.

According to the artist, the graph is what responds faster to “the processes that we live socially, past and present duels.”

Altered territories. Iulia akhmadeva It will remain until July 6 at the National Museum of the stamp (Hidalgo 39, Plaza de la Santa Veracruz, Centro).