Special for in red

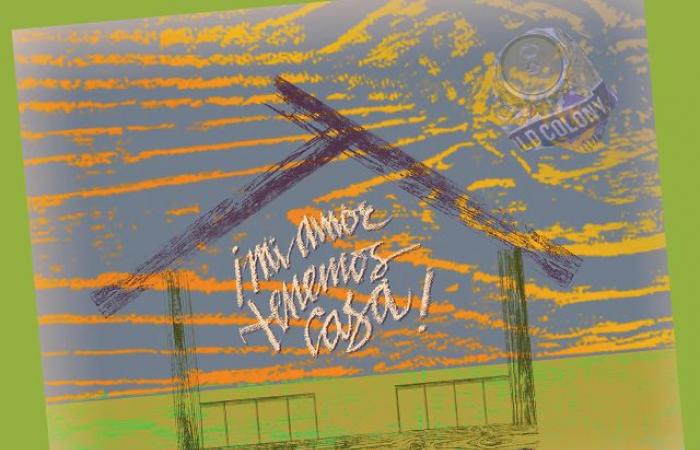

Since I came to my hands I knew this was a book that I had to read urgently, but with great attention. And so it was: as soon as I ended with a promised job and with a deadline that took me, I began to read My love, we have a house! (San Juan, Puerto Rican Foundation of the Humanities, 2024) of the architect and urban planner Edwin Quiles Rodríguez. This book studies the formation of the so -called suburbs in San Juan, especially in Santurce. And his reading leads me to write these pages.

Why do I dare to write about a book that seems to fall into an intellectual context that I supposedly have no entry permission? What do I have to say about a book that investigates the urban development of San Juan, looking at emblematic places such as the Fink, after workshops and Barrio Obrero? Someone who adopts a rigid demarcation in the research areas and in academic disciplines will say that I should not comment on the book of Quiles because I am neither an architect nor urban planner. “Zapatero to your shoe” will tell me or, better, for other supposed comments of mine, they have told me. For those guards of disciplinary demarcations I can only comment on a literary text, nothing more. But I have always believed that my shoes are the books, no matter their subject. I am a reader and with pride I declare it! Of course, I don’t think I can comment as a specialist as a text. But Nilita Vietos Gastón taught me, in theory and with her practice, that one can approach any text simplely and honestly as a reader and that everything human is open to those who approach it with curiosity and honesty, whatever it is or read what you read. Thus, as a mere reader and not as a specialist in the field of urbanism and architecture, I approach this book.

But the book opens to any reader because it adopts a humanistic approach and, sometimes and unintentionally, points to intellectual and aesthetic fields that welcome readers of other disciplines. Is that this book lends many readings; Even invites and induces them. That is because, despite the scholarly quotes to historians, sociologists and anthropologists and the abundant tests based on percentages of population increases or other important social changes, this is a book that opens to any interested reader because those tests and those appointments do not serve to deny access to those who open their pages. On the contrary, they invite reading and comment. In addition, the book adopts a refreshing approach that breaks with the rigid borders of academic plots. This book invites us to enter him as a neighboring hospital of Arrabal would have done, as one of the inhabitants of the improvised and humble houses built in Hoare, high of the goat or in the Gandul.

My love, we have a house! – I point out that I do not like the title, since it does not seem appropriate for the content of the book – it is written in an enjoyable way; We do not face a heavy academic brick. Not only Quiles cites consecrated writers – Neruda, García Márquez, Lloréns – to support his ideas, but he frequently uses a poetic language to describe the suburb: “The woods of the catwalks, the walls, the roof and the floor slept restless, frowning and creaking as if it were the bones of a growing body.” (Page 140) But those descriptions of poetic tones do not deny or hide the painful reality of life in the suburb where “yellow fever, anquilaostomiasis, poor nutrition and skin diseases reigned to bathe in the púrtrida waters of the pipe.” (Page 140) In addition, to the poetic tone that marks many passages of the book, we must add the author’s narratives or others based on the multiple interviews he made to those who had been inhabitants of the suburbs, narratives that also give the book a literary tone since he approaches the testimony, a genre so popular in our days.

There are multiple and very different approaches that this book allows us and even proposes. For example, if we look at the quotes to other scholars of the topic – Helen Safa, Jorge Duany, Rosa Vanessa Otero – a brief history of scholars who have investigated the subject could be delineated with them. Or if we look at the references to the signs of commitment to the inhabitants of the suburbs that then expressed the leftist parties, especially the Puerto Rican Communist Party, we could draw another different story. Likewise, if we look at the references to music, cinema and literature that has dealt with the subject of the suburb – curiously, the archetypal story is never mentioned on the subject: “In the background of the pipe there is a black The cart From René Marqués – we could build another line, the development of the theme in the arts. Interestingly, the paintings and engravings of Carlos Raquel Rivera, Rafael Tufiño and Myrna Báez are also absent from that possible line who so effectively portrayed that world.

Of all the ramifications of the theme that Quiles gives us more than others his definition of the aesthetics that dominates the contractions and life of the suburb, what we could call the suburb aesthetics. It will seem to the first contradictory and even offensive instance to think about such a current, since the aesthetics are usually associated with the refined world of the so -called high culture. But it is not so and quiles, with an acute and penetrating look, he discovers that in that world of poverty and injustice imposed by social circumstances on the inhabitants of the Arrabal, an aesthetic, sometimes accidental and sometimes very well thought out is present. Let’s look a little more detail what Quiles tells us and why postulous that that line can be drawn on aesthetic thinking in the text.

In Chapter 4, entitled “The Foundation of the Arrabales: Strategies for clandestine construction”, we find the main keys to the subject that interests me, although the whole book is splashed from ideas about it. First, Quiles part that humans build our environment with “wishes, sweat, charm, pain, frustration, […] joys, stories and brands that we leave… ”. (page 111) We do not build it only with steel, marble, glass and cement and, above all, it does not matter if others do not consider our construction as something valid, of artistic amount and worthy of being appreciated. Therefore the fortuitous act, improvisation and urgency can reflect that metal aesthetic. This leads to a hopeful vision of this world that is usually seen as negative:

The suburb was a world between becoming and undoing. A world whose genesis was the broken, obsolete and destroyed, subject to the imagination and capacity to build the pre -precarie alarifesandd. (Page 112)

Arrabal builders are alarifes or architects that start from the precarious, of what is found, from what is rescued, from what others discard to create their world, world that, despite what others say, is based on their own aesthetic.

The aesthetics described here has parallels with which Carlos Monsiváis, who on several occasions Quiles quotes, finds in Mexico City and with which Luis Rafael Sánchez Sánchez proposes particularly in his aesthetics of the foul. Sánchez Quiles never quotes him, but, to show the parallels between them, let’s remember his brilliant essay “Another desperate song” (2004), where from a graphite that finds in a public wall just at the entrance of the pipe of Martín Peña Sánchez demonstrates that poetry, good poetry, can also be found in the suburb and this can recall and even rewrite a poem of Neruda.

If I am allowed a scholarly note, I point out that this suburb aesthetic is the one that the French theorists, especially the structuralist anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, call “bricolage.” This is an injured aesthetic that is worth creating what is tende on hand. For many the “Bricolage” is a lack of aesthetic principles, but for observers capable of seeing beyond what was accepted by the ruling class, this is a valid, effective and claiming way to create. Think, for example, in the pieces of Nick Quijano built with flip flops and other objects found on the beach of La Perla; That is “Bricolage”, although it is the creation of an educated and aware artist of the aesthetic foundations of his work. The “Bricolage” of the suburb is more spontaneous and even unconscious. But Quiles recognizes its value and so establishes, although it never uses the scholarly term that has a strong and repellent – for some – academic tufillo. Therefore, it establishes very clearly the character of that aesthetic that seems not to fit within the field of the arts: Because of this ability to put shapes, textures and colors, for taking different references to create their own miscegenation, the architecture of the suburbs seems to look out, as Alejo Carpentier said, to barochism. (Page 114)

Quiles offers us from very early in his book a comprehensive image of the suburb from that aesthetic perspective and therefore defines it. For him, el arrabal is[j]Unte of different pieces from which a functional and baroque aesthetic is forged, product of the mixture and the daring and inevitable combination of textures, surfaces and geometries very close to fantasy and “disorder. (Page 24)

Fantasy, disorder, social commitment, popular culture, “Bricolage”, miscegenation, in short, barochism: who knows me will immediately realize why I am interested in this important book.

But that is very clear: this exploration of the suburb aesthetics is not a glorification of poverty or social injustice. It is, however, an attempt to find values and forces in what for others is something despicable, without value, without aesthetic meaning. Carpentier, Monsiváis, Sánchez and Quiles do not cover social injustice with a layer of erudition or intellectual play, or false refinement but they find, in what others discard as unusable, features that seem paradoxical, contradictory and that, in the background, serve to redeem what the established society despises. They find what others rule out a work with a fundamentally aesthetic, with an intellectual meaning and with a political purpose.

I point here a line of thought and argumentation that I find in the book of Quiles. I already said that as a reader I approach every text that I read from a personal perspective. This does not mean that it believes that mine is the only way to approach any book or this in particular. Since that of Quiles is very rich in information, in ideas and proposals, each reader can read to it in a different way, diverse to the one I propose here.

This is my way of understanding, to a large extent, My love, we have a house!. My approach justifies that I can also comment on a book by an urban architect and planner. Every reading can be wide, but none is alien. This is especially when we approach a text as rich and suggestive as this one of Edwin Quiles.