By Matthew RicketsonDeakin University

“The price of liberty is eternal vigilance.” This famous quote is often attributed to Thomas Jefferson, the founder of American democracy.

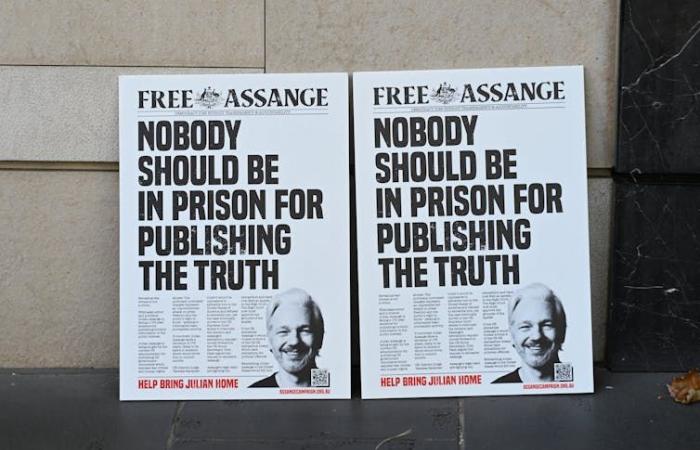

For Julian Assange, the price of freedom has been five years in prison as he fought extradition to the United States to face charges that no democracy should ever have brought. That is why his release and return to Australia is deeply encouraging news.

However, it is deeply disheartening to see the lengths to which a nation state has gone to punish a publisher who published documents and videos revealing that US troops committed alleged war crimes in the Iraq War two decades ago.

Assange has been a controversial international figure for so many years that it is easy to lose sight of what he has done, why he has attracted such fiercely polarised opinions and what his imprisonment means for journalism and democracy.

What have you done?

An Australian national, he rose to fame in the 2000s for creating WikiLeaks, a website that published leaks of government, military and intelligence documents that revealed a whole series of scandals in various countries.

Most of the documents were published in full. For Assange, this fulfilled his goal of radical transparency. For his detractors, the publication could endanger the lives of intelligence sources.

This remains a point of controversy. Some have claimed that Assange’s attitude towards the people named in the leaked documents was arrogant and that the publication of some documents was simply unnecessary.

But critics, especially the US military, have been unable to point to specific cases in which the publication of documents has led to the death of a person. In 2010, Joe Biden, then vice president, acknowledged that WikiLeaks publications had not caused “substantial harm.” Then-US Secretary of Defense Robert Gates said at the time that countries dealt with the United States because it was convenient for them, “not because they think we can keep secrets.”

The key to WikiLeaks’ success was that Assange and his colleagues found a way to encrypt documents and make them untraceable, to protect whistleblowing sources from official retaliation. It was a strategy later copied by major media organizations.

WikiLeaks rose to worldwide fame in April 2010 when it published hundreds of thousands of documents that provided the raw material for a shadowy history of the disastrous wars waged by the Americans and their allies, including Australia, in Afghanistan and Iraq following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.

Documents are one thing and videos are another. Assange published a video titled Collateral Murder (Collateral Murder). It shows American soldiers in a helicopter shooting and killing Iraqi civilians and two Reuters journalists in 2007.

Aside from the way the soldiers in the video speak – “Hahaha, I hit them”, “Good”, “Nice shot” – it seems that most of the victims are civilians and that the journalists’ cameras are mistaken for rifles.

When one of the wounded attempts to crawl to safety, the helicopter crew, rather than allowing their American comrades on the ground to take him prisoner as the rules of war require, asks permission to shoot him again.

Soldiers are given permission to shoot. The wounded man is taken to a nearby minibus, which is shot with the helicopter’s gun. The driver and two other rescuers die instantly, while the driver’s two young children who were inside are seriously injured.

The US military leadership investigated the matter, concluding that the soldiers acted in accordance with the rules of war. Despite this, the US prosecution did not include the video in its indictment against Assange, leading to accusations that it did not want the material to be exposed to the public any further.

Likewise, the public would never have known that an alleged war crime had been committed without the release of the video.

Exile

Assange and WikiLeaks had not taken long to become famous when everything began to fall apart.

He was accused of sexually assaulting two women. He took refuge in the Ecuadorian embassy in London for seven years to avoid being extradited to Sweden for questioning about the alleged assaults, from where he could then be extradited to the United States. He was then imprisoned in England for the past five years.

It has been confusing to follow the byzantine twists and turns of the Assange case. His character has been vilified by his opponents and revered by his supporters.

Even journalists, who are supposed to be in the same business of speaking truth to power, have adopted contradictory stances toward Assange, oscillating between giving him awards (a Walkley for his outstanding contribution to journalism) and shunning him (The New York Times (He has said that he is more of a source than a journalist).

Personal suffering

After Sweden eventually dropped the sexual assault charges, the U.S. government quickly escalated its request to extradite him to face charges under the Espionage Act, which, if successful, could have led to a prison sentence of up to 175 years.

The long, drawn-out and very public case, legal or not, has raised issues that have not yet been fully addressed.

Nils Melzer, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture, thoroughly investigated the case against Assange and laid it out in forensic detail in a 2022 book.

In it, he wrote:

The Assange case is the story of a man who is being persecuted and mistreated for exposing the dirty secrets of the powerful, including war crimes, torture and corruption. It is the story of deliberate judicial arbitrariness in Western democracies that are otherwise keen to present themselves as exemplary in human rights matters.

It has also suffered significantly in legal and diplomatic processes in at least four countries.

Since he was jailed in 2019, Assange’s team says he spent much of that time in solitary confinement for up to 23 hours a day, denied all but the most limited access to his legal team (not to mention the family and friends) and was kept in a glass bubble during his seemingly endless extradition hearing.

His physical and mental health has suffered to the point that he has been placed on suicide watch. Again, that seems to be the point, as Melzer writes:

The main objective of persecuting Assange is not – and has never been – to punish him personally, but to establish a generic precedent with a global deterrent effect on other journalists, publicists and activists.

So while Assange himself is human and his suffering is real, his prolonged time in the spotlight has made him more of a symbol. Whether he is seen as the hero who exposes governments’ dirty secrets, or as something far more sinister.

If their experience has taught us anything, it is that speaking truth to power can have an unfathomable personal cost.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.