The exhibition by the group of visual artists Mondongo (Juliana Laffitte and Manuel Mendanha) at Malba is a hymn to the organization of workers. Starting from an exercise to make the towns visible and an apparent impossibility of exit, he proposes a path: organize and fight. The exhibition presents contradictions of social reality under capitalism, as well as of artistic practice, taking charge of both the limits and the potential of art to intervene in the transformation of reality.

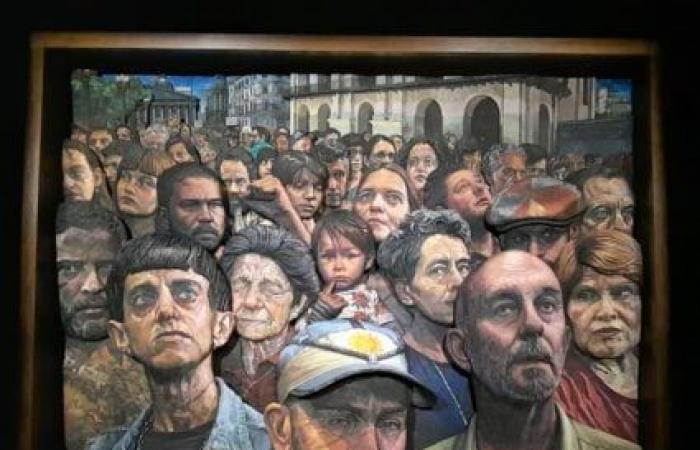

The “jewel” of the exhibition is a contemporary version of “Manifestación” by Antonio Berni, located in Buenos Aires, around the Plaza de Mayo. The work is striking for its execution, given that all the color is applied with plasticine, condensing 20 years of Mondongo’s experimentation with that material. At the same time, it is a high relief painting, each protester has volume, based on digital modeling of photos taken in his studio and printed in 3D. That alone is worth the visit, but the exhibition is much more than the enormous technique of Laffitte and Mendanha.

Although it is presented as a tribute to Berni, it connects two icons of the so-called “social painting” of Argentina: “Without bread and without work”, painted in 1890 by Ernesto de la Cárcova and the already mentioned “Manifestación” by Berni, from 1934 , where a popular mobilization demands, precisely, bread and work. Furthermore, it dialogues with Berni’s paintings, engravings and collages about the Rosario villas and his archetypal character Juanito Laguna, a child composed of urban and industrial waste, which is presented as “discard” for capital.

Although there are very few pieces, the exhibition is a spatial labyrinth, with layers of representation. For example, they recreate De la Cárcova’s painting with Berni’s methods and themes (the slum and the discarded materials) and connect images from the beginning and end of the tour through countless details. The exhibition is organized in two large spaces, an installation that recreates a slum, packed with things, and a very dark room measuring 21 meters where only three paintings are displayed: Berni’s original work, “Manifestación”; on the opposite wall, Mondongo’s version and, between the two, “Villa II,” from the Sur Global series, a circular painting that also presents a slum, in plasticine, with many nods to Berni and echoes of both the Argentine settlements and the favelas.

The two sectors contrast like the villa in Malba. Between the two spaces there is an enigmatic, circular work that looks like a portal to another dimension, like a wormhole, where exposed brick walls with broken glass on top spiral, like those placed on dividing walls. In the center of the circle there is a counter that always starts over and at each repetition it tells us: Bye. The sensation is distressing, we sink into a world of private property, segregation, exclusion. It makes you want to crush the clay bricks and mold something else.

In the first sector, the public enters a reproduction of a villa, whose ceilings can be seen from the upper floors of the museum, scandalizing conservative critics who accept a painting of a villa, but not being invited to enter one, although be lies. From its interior you can also see, through the roof, the stunning structure of Malba, recreating the real contrasts between the precarious settlements and the luxury towers that surround them.

Mondongo borrows an expression from Berni that says that when faced with a reality that “breaks the eyes”, the artist “is forced to live with his eyes open”. And they seem to force the spectator to do the same. Therefore, they bring into play nothing more and nothing less than the very problem of representation and the relationship between art and social protest. The problem they develop is how to represent poverty and the organization of workers.

The main room of the villa reproduces De la Cárcova’s painting twice. On one side, painted on a flag, with the reeds ready to go out and march; on the other, in space: the room we enter is the one in the painting.

In the original painting, a couple is seen sitting at a table under a window. Outside, the police are seen suppressing a strike. The woman is holding her baby in her arms, with nothing to offer him, and the man is tensely looking out of the window, his fist impotently hitting the table, next to his lifeless work tools. In the village of Mondongo, there is the little table under the window, the two chairs in the same position and the work tools, except that in this case, they are those of the painter: a palette, brushes and paints. The slum-dweller-artist has painted the painting-flag that is leaning against the opposite wall, ready for the demonstration.

The closed, impotent hand of the worker who did not go on strike in “Without bread and without work” appears at the end of the route, in the plasticine version of “Manifestación”: it becomes the raised fist of the Trotskyist (image taken from a member of the Workers’ Party, a friend of the artists), almost in the center of the mobilization. The Trotskyist and the child are the only ones who look unscathed, without avoiding their gaze, nor raising their gaze to heaven, without crying, without despair, without closing their eyes. Helplessness is resolved in organization and action.

The differences between Mondongo’s “Manifestation” and Berni’s present interesting problems. In the original, workers at a Rosario refinery look towards the same point, probably listening to a speaker. Mondongo chooses as models a group of characters from culture and art (Fogwill, Albertina Carri, Sergio Bizzio, Minujín…) and family and friends, so the working class, protagonist of the original work, is diluted in a movement more heterogeneous popular movement, putting into dialogue the power of mobilizations like that of April 23 and the problem of the direction of the popular movement, since almost no one knows where to look.

It does not go unnoticed that the ticket to Malba costs $5,000 (2,500 with a discount and with only one free day in the week, Wednesdays), as well as the recent purchase that Eduardo Constantini made of Mondongo’s version of “Manifestación” -according to La Nation, in six figures in dollars.

Some commentators on social networks talk about snobbery for creating a villa for those who will never go to one and others respond that those in the villa do not need to go to Malba to know that the villa exists. In contrast, we defend the right to art and reject the underestimation of the popular masses, since those who live in the towns probably draw more conclusions and sensations from the exhibition than the petite bourgeoisie that frequents Malba. The aesthetic experience is always revealing of new knowledge, the value of art is the opportunity to know ourselves and interrogate the world around us, through experiences that we would not have otherwise, whether it shows us a known reality or immerse yourself in the unknown, and that should be for everyone. It is worth mentioning that Constantini is the owner of almost all the pieces that make up Latin American art. His “heritage” should be public and accessible to all.

In an almost hidden corner of the village of Mondongo, there is a small blue corner where a real plant is drying, which no one in the museum will be watering. Next to it, an empty chair, an image of the white rabbit, like the one in “The Matrix” and “Alice in Wonderland” that invites illusion and the distortion of reality. Whoever wants to sit and watch the plant die, whoever wants to water it or take it out of the museum, because it is not made of plasticine and it will die; whoever does this, should turn their back on the rabbit and read a word stamped on a piece of wood: STRENGTH.