Gudanz was born in Ulaanbaatar to Argentine parents: Ramiro and Diana. He speaks Spanish perfectly, with an exotic accent.

Diana, operational manager of a multinational food processing company, was selected to manage the plant in the capital of Mongolia. Ramiro accepted the challenge. They have already been living in Asia for 14 years. Diana’s birth in the Khan’s lands, two years after settling in, was a festive confirmation for the couple that they had made the right decision.

Although Buenos Aires is an unavoidable reference for Gudanz, who will soon turn 13, they have not returned to Argentina.

There were no major reasons for the visit and they do not appear on the near horizon either. Their days in Mongolia are peaceful: they have visited China, Japan and Paris. When appropriate, they will set foot in Buenos Aires. Ramiro is an effective web designer, he works from home, in the northwest of Ulaanbaatar, a kilometer and a half from the city’s commercial center.

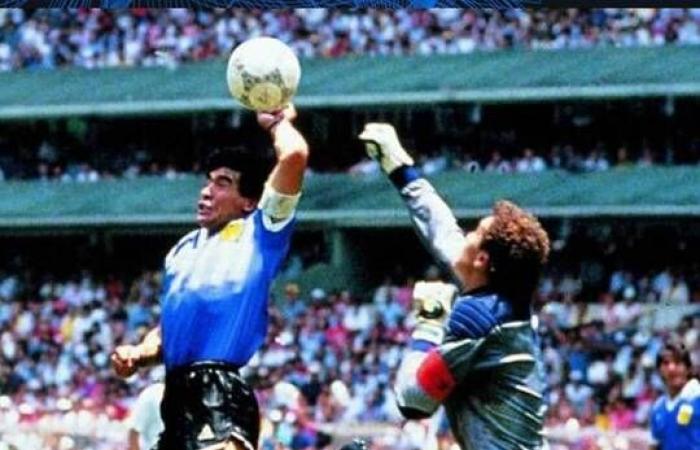

Among the Argentine memorabilia that Ramiro and Gudanz share as man to man, Maradona’s goal against the English in 1986 figures prominently. The goal in the air.

“More than thirty years after that game at the Azteca Stadium, they shouted it together as if it were happening the first time they saw it“

Gudanz attends a multilingual school, generally speaking English, and with specific schedules for a review, with personalized teachers, based on the languages of origin of each student. None of his teammates has ever mentioned any particularity about that Maradona goal. Ramiro commented on it with Gudanz as if it were a legitimate goal with his head, without clarifying. At no point did he specifically refer to a “headbutt.” Not even Gudanz consulted about it. They just celebrated it.

More than thirty years after that match at the Azteca Stadium, they shouted it together as if it were happening the first time they saw it, in a film without a story, scored by the Rolling Stones and Serú Girán, bought by Ramiro from a collector in the Web. Did you choose that stripped-down version on purpose? The issue did not go further.

That goal is for Gudanz one of the historical events that connect him with the country of his parents. Gudanz is a friendly soccer player, interested but not particularly gifted. However, as a spectator, he feels the call of his ancestors in this sport. He is an integral part of Argentina at a distance from him.

One afternoon Gudanz tells Ramiro that a Mexican student has joined the course. They will soon finish seventh: high school is another matter. The Mexican, Oliverio, like Gudanz, places his ties with Latin America in the history of football. Oliverio was born in Mexico City. He migrated to Mongolia with his parents at age 9. His father has started a Mexican restaurant, his mother is a housewife. He knows the 86 World Cup inside out, Gudanz enthusiastically tells Ramiro.

“How will the fact that Maradona scored that goal outside the rules impact the boy?“

That night Gudanz’s father does not sleep. What if his Spanish-speaking partner informs Gudanz of the hand of God? Precisely at the end of his twelve years, when the young Gudanz approaches the age of responsibility. How will the fact that Maradona scored that goal outside the rules impact the boy? What will you think when you know that that iconic goal had more cunning than merit? Gudanz is a discreetly honest student, attached to effort, to the acquisition of knowledge. How will he regard his father when he discovers that throughout his childhood he presented to her what was an infraction as a myth?

In the morning, when he takes Gudanz to school, Ramiro remains unusually silent. Gudanz barely asks what’s wrong, and the father responds that he’s worried about an upcoming job. But that same noon Ramiro decides that when Gudanz returns from school, even at the risk that Oliverio has not told him and will never tell him anything, he will reveal the truth: Maradona scored the goal with his hand.

Diana has returned early from work. Ramiro warns her that at nightfall she will go for a walk with Gudanz, perhaps they will stay for dinner downtown, she will transmit the secret to him as a ritual of passage to adulthood. Diana smiles at the seriousness with which Ramiro takes on the conflict, but she does not object. The die is cast.

Ramiro and Gudanz have dinner early, at Oliverio’s father’s Mexican restaurant, on a side street in the center of Ulaanbaatar. The occasion warrants it.

Ramiro suddenly finds himself sweating. He is not the spicy taco, nor the Margarita drink. The moment has come. The quesadillas and guacamole in their respective small, white dishes, in suspense until the earthquake of blood subsides.

“Son, about Maradona’s goal…” Ramiro says after a sangrita tequila. The goal in the air.

Gudanz turns pale. Or does Ramiro think so?

Undoubtedly the boy’s expression is not usual. A mixture of fear and perplexity. Ramiro hesitates. He is curious about his son’s reaction. Why the apprehension, if he doesn’t know what he will tell her?

“That goal,” Ramiro finally murmurs, and raises his voice; If he is going to say it, it must be conclusive—Maradona did it with his hand. Beyond all reasonable doubt. Maradona himself confessed it.

“How could they judge a player, any athlete, in that sport, in those circumstances, without somehow putting themselves in their place?“

He doesn’t call him “Diego” or “El Ten”. The truth requires a certain solemnity, attachment to the facts (reality is part of the truth, but it is not its only component).

Now Gudanz, much to his father’s surprise, breathes a sigh of relief. The colors return to the boy’s face.

“Of course,” confirms Gudanz in his exotic Spanish. The hand of God.

And he adds, after drinking his lemonade with ginger and cilantro:

“I thought you didn’t know.”

His son—Ramiro wonders how long—was protecting him from that information, preserving the secret to share pure joy with his father.

Ramiro looks at his son with his chest about to burst with pride.

“I often wonder what I would have done in a situation like that,” Gudanz continues. It’s not something you can know if it doesn’t happen to you. You jump, you don’t arrive… You automatically raise your hand. They don’t see you. What are you doing?

Ramiro had never thought about it like that. How could they judge a player, any athlete, in that sport, in those circumstances, without somehow putting themselves in their place? How would we have acted? His son asks him. It is not easy for the father to give an answer. But he doesn’t need it either: Gudanz’s secret passage to adulthood is also a secret for his father. Maybe that’s what it is.

3/5

(2 Ratings. Rate this article, please)