Legend has it that one day Rius —at the age of 21 and in charge of a funeral home— was doodling cartoons, when the director of the magazine Ja-já discovered him among the funeral service and invited him to collaborate on its pages. The story goes that on that day the future of Eduardo del Rio: He canceled his plan to take his course as a cadaver embalmer and began a fruitful career in cartooning in the pages of Ja-já, a magazine in which the origins of the man who is considered one of the great pillars of the Mexican humor.

To Eduardo del Río, better known as Rius, Carlos Monsivais I considered it the third Mexico’s educational system, for its informative capacity on political and social issues. Almost seven years after his death, which occurred on August 8, 2017, the cartoonist Luis Gantus, his friend and student, publishes El Ja-já de Rius (Grijalbo), a book that rescues 200 of the first caricatures – several of them in color or collages – made by Rius in the 1950s and published in the magazine Ja-já, where he debuted in 1954.

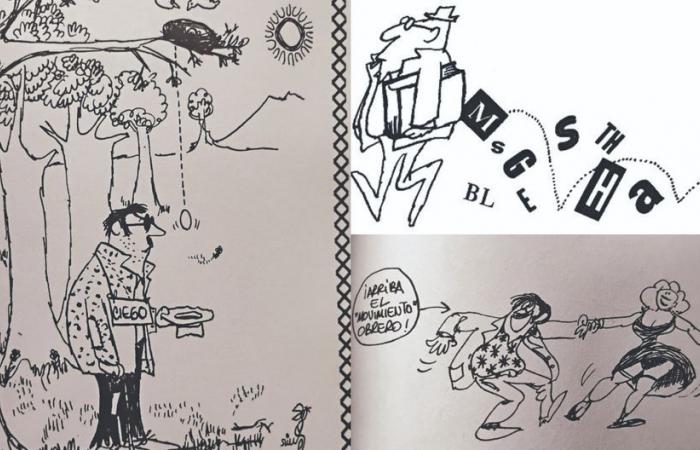

Gantús tells EL UNIVERSAL that an almost complete collection of Ja-já came into his hands a few years ago, and the first thing he thought was that in that mythical magazine “which sells a lot, but is poorly regarded” he had debuted Sergio Aragonesthe artist of spanish comics who is famous for his collaborations in the MAD Magazine. Then he remembered that Aragonés and Rius had met on those pages, and as he kept looking at them, he almost accidentally put aside Rius’s caricatures, the first of his career. “The first thing I realized is that Rius was already there from the beginning. In those caricatures you start to see the iconoclast, you start to detect the different; you see how he was looking for new forms of expression. You’re talking about it being the beginning of his career. There are jokes, although some tend to be like the common theme; But there are some that are even different, with a certain pun, with a certain particular acidity,” he says. Luis Gantús.

Read also: From theater to cinema, “Ad Absurdum” premieres today

There he began to imagine this book, which is a new book by Rius, although it is a rescue of the first Rius. A book whose cover and interior were designed by Rius’ daughter, Citlali del Río Flores. A work that includes a prologue by the editor of Rius’ books for more than four decades, Ariel Rosales; an introduction by Luis Gantús, as well as special comics made by other monkeys or cartoonists, like his friend Sergio Aragones; as well as creators from younger generations, such as the Mexicans Iurhi Peña and Augusto Moraand the Colombian Power Paolawhich together give a broad overview of Rius’ work and style.

“Eduardo del Río, Rius, achieved with his work what no other cartoonist in the entire world has achieved: to be the voice of his native country, unmasking falsehoods with his fine sense of humor and his advice,” says Aragonés in the two-page comic strip with which he pays tribute to his friend and mentor.

Gantús points out that just by looking at the section of old cartoonists, anyone realizes that Rius was already there. “I think that Rius was already there within Rius. That he was already in this recognized author, this popularizer and creator of books, that narrator was already there, that humorist, that character, that creator of different things and you can see it in the old cartoonists, you can see it when he cuts out the photographs that are a technique that he used a lot in his books,” says Gantús, who points out that the book also included the Cancionero. A section of El Ja-já de Rius, in which the reader and admirer will be able to discover a facet of the cartoonist that would later be a constant in his books and comics: the use of Photographsperhaps greatly influenced by the North American magazine MAD.

And Rius’s Ja-já also contains three unpublished linocuts by Rius, made in the last years of his life and whose creation date is “around” 2008, in which, according to Gantús, “the master” returns to the color drawings he made in his beginnings, when he began doing white humor, simple jokes that, without a doubt, are the most unknown side of the master of several generations of cartoonists, great guru of left-wing thought, and disseminator of the facts and “horrors” of the Catholic and Apostolic Church.

Read also: Amalia Hernandez’s Ballet will arrive for the first time at the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles on July 18

One of the most endearing texts is that of its editor Ariel Rosaleswho says that he talked a lot with Rius about hundreds of topics, including Ja-já. “He told me that his career developed there learning of the trade, because he had to make jokes dancing with the ugliest: white humor.” He also told him that political caricature was always determined by a news item or a politician and that is what the cartoonist must get away from, but not so with humor as such, “there is nothing to hold on to. You practically have to invent an alternate reality to the everyday one,” Rosales says he told him. Reading his books and now knowing his beginnings, Rosales indicates that in his beginner jokes he achieves something brilliant: “With his white humor, Rius approaches the absurdity of the humorous genre “which Chesterton accurately analyses and Carroll brilliantly cultivates.”

Comedian beyond politics

Something that Gantús and CitlaliRius’s daughter, was to show the public “the Rius that we knew. The one that I had the great opportunity to meet, the one that his daughter remembers. It was the Rius with a great sense of humor, it was the funny Rius. It was the Rius who sought to make people laugh, although most people place him by his political work, or the religious issue, or the issue of the vegetarianism. This Rius was the one that many of us met at the events where we met, at the meetings, a closer, funnier Rius, very focused on humor, and that humor was also reflected in all his work, not just that. political criticism or political cartoon. He had that latent sense of humor that allows him to create things like Los Súpermachos or Los agachados, where he uses narrative, humor, similesto create small microcosms of a huge society that are also a masterpiece,” says Gantús.

When asked if Rius was forced to assume a cartoon policy, to talk more about the social and political and the problems that afflict Mexico, Luis Gantús says no. “It’s not so much that he was forced. Let’s take into account that he started this in the 50s, we are talking about his first collaboration being in 54, and that in 58 comes the Cuban Revolution that changes the mentality of many young people, and he wanted to say it and he wanted to wear his overalls. to say. Several factors come together. One is that he knew that in Mexico white humor was not going to give him a living, that is one of the reasons why Sergio Aragonés goes to the United States to try his luck; and Eduardo himself had a very strong political charge, an inclination, like all young people, and more so at that time, admirers of what the Cuban Revolution achieved at the time, and Rius decided to express it, but he was also rebellious, he was rebellious, and “He decided to take the path of trying to say things that at that moment were impossible to say.”

That is also in its beginnings, that rebellious spirit, that revolutionary spirit. And with that commitment he took the political issue, the social issue, to continue making white humor, says Gantús, who in addition to being a cartoonist is a researcher and historiographer. “He did that type of humor and had it on the surface, but he had a very marked and very serious political commitment.”

And he assures that it is so clear that there was a moment in his life when he was kicked out from everywhere and that is when he started to make his comic strip Los Supermachos and reached another market and another audience, “that is where he begins to change, there he mixes humor with a lot of the social and political burden that he wanted to express. I think that is where you can best understand the humorous and social part of Rius, in Los supermales, and in Los agachados; he became more popular. Los supermachos was a masterpiece of humor, of dialogues of irony, of sarcasm that is most present when he works on La garpata, where he stepped on so many calluses in the government,” he assures.

A few years before he died, Rius had the desire to recover or return to simple humor.

“Even though he still carries that burden and publishes things like Sálvanos del PRI, he is already starting to make other kinds of books, like one about Don Quixote that was published in Spain; he wanted to get back to doing humor, knowing that he was already Rius. He devoted himself a lot to painting, which he liked a lot. People who didn’t know that facet of his life can get a slight insight here.”

Join our channel

EL UNIVERSAL is now on Whatsapp! From your mobile device, find out about the most relevant news of the day, opinion articles, entertainment, trends and more.