“They are scared,” said the president, Gustavo Petro, in a defiant tone. “Of course, we’re scared,” responds Bruce Mac Master, the leader of the country’s largest economic union, the Andi. “And Petro likes to scare.”

Petro’s challenge was launched in a political key last week, in response to the proposal of former president, Iván Duque, to put together an alliance of presidential candidates to confront the left in 2026. Duque proposed it at the bankers’ conference, Asobancaria. And Petro’s response was read in a broader context, from the private sector, as another fact that erodes trust in the government.

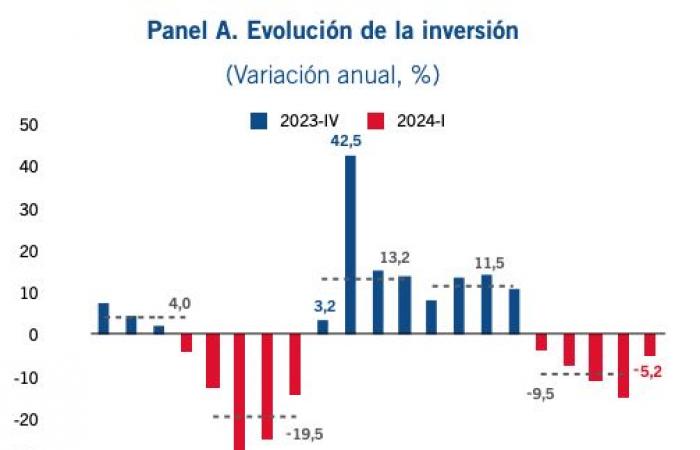

These cracks are taking their toll on the economy and the government, despite clear efforts by the Ministry of Finance to maintain fiscal orthodoxy, such as reducing fuel subsidies and remembering the budget. Still, the “animal spirits” of economics, of which economist John Maynard Keynes spoke, are agitated. Private sector investment, the money that entrepreneurs spend to generate more wealth in the future, on things like machines and roads, has fallen for more than a year. In 2023, it fell 9.5%. In the first quarter of 2024 it improved somewhat, but it continues to fall 5.2%, according to Dane. “The contractions (…) equal, in duration, what was observed during the pandemic,” notes Fedesarrollo, an economic think tank.

That partly explains the low growth of the economy, and the government’s low collections, which forced it to make the painful budget cut. According to businessmen, union leaders, economists and academics consulted by La Silla Vacía, in the midst there have been many self-inflicted blows that were not part of the government program with which Petro was elected. They go beyond the high interest rates of the Bank of the Republic, the tax reform of José Antonio Ocampo, which punished the private sector, external factors and the fact of having a left-wing government. With very similar characteristics, in Brazil, with “Lula”, there was a record of private investment last year.

These are the key factors behind an avoidable breakdown of investor confidence:

From sectoral attacks to general uncertainty

Two days after claiming that the establishment was “scared,” Petro announced on Twitter (now X) that he was suspending coal exports to Israel, “until the genocide stops.” The message was accompanied by a draft decree already prepared — which has not yet been signed — that has dubious legality and could lead to million-dollar fines for Colombia.

The president went from throwing taunts in the faces of businessmen at the beginning of the government, to taking specific sectoral measures, via decree or administrative actions, that break the rules of the game in each sector. “Things like coal generate distrust in all businessmen,” says Thierry Ways, owner of a medium-sized company in Barranquilla and columnist for El Tiempo. “The feeling is sown that an arbitrary measure can reach everyone. For the investor, the climate it generates is one of distrust and uncertainty.” And measures of this type have arrived in several sectors.

Oil and coal like cocaine. Stopping oil exploration contracts was an explicit proposal by Petro during the campaign, which he made effective against the advice of key members of his first economic cabinet. But it went further. “The comparison of oil with cocaine sent a less than encouraging signal to investors,” says Luis Fernando Mejía, director of Fedesarrollo. Now coal enters the debate with the export ban to Israel.

The sector is a source of key tax revenue, through royalties and Ecopetrol, and the source of a third of foreign direct investment. In April 2024, according to the Bank of the Republic, this investment rate fell 51% compared to 2023. In return, there is no clear energy transition plan, and the government has placed obstacles on existing alternative energy projects. .

The failed takeover of the Creg to lower electricity rates. At the congress of the public service companies union, Petro announced that the Creg would intervene, using a law from the Duque government. The objective was to lower electricity rates, and “regulate markets based on universal law.” The Council of State overturned the decree months later. “It started with the electricity sector, and continued with infrastructure and health,” recalls Mauricio Reina, economic analyst and RedMas commentator.

The blow to infrastructure with tolls. In January 2023, a decree was issued by the Ministry of Transportation freezing toll rates, which according to previously signed contracts are adjusted annually for inflation. It came with Petro’s threat of sanctions for those who did not comply. The State promised to assume the cost, estimated at $800 billion a year, but at the end of 2023 it reversed the measure. “In addition to the fiscal cost, there was a reputational cost among potential investors that the government, at any time, can make the same decision for a political issue,” says Mejía, from Fedesarrollo. Today the outlook for 5G concessions is uncertain, in a sector that in 2021 invested 1.2% of GDP.

The power of Super in health. From the beginning of the government it was clear that Petro’s winning program included a reform so that health “was not a business.” But the intention to end the insurance role of the EPS was defeated in Congress. In retaliation, the government created a crisis, in part, by using the broad power of the Health Superintendency to intervene in insurance companies. First it was Sanitas, one of those with the best satisfaction indicators, then the New EPS. “It was the use of the administrative police,” says Mac Master, who has several insurers in Andi.

All the reforms at once, and a constituent on top

After having achieved the approval of the largest tax reform in recent history, President Petro embarked on the reform of all social security: health, pensions and work.

The three reforms, presented successively in the same legislature, launched with a balcony speech and union demonstrations, came with a warning from the president: “Reforms and revolution go hand in hand, the attempt to restrict the reforms can lead to a revolution,” he said in a May 1 speech from the balcony of the Casa de Nariño.

Even heterodox economic observers warn of an avoidable mistake. “When the rules of the game change, time horizons are relevant. The strategy of voting on all the reforms at the same time is not wise because it increases conflict,” says Camilo Guevara, professor of economics at the National University.

Furthermore, all of the reforms touched on key aspects of the way in which the private sector is interwoven with the State in Colombia. Health with the EPS, pensions with private funds, and labor reform with the private employment sector, which is 94%.

The attempt to process them through an announced “national agreement” failed. The health reform succumbed, and gave way to the aforementioned use of administrative action, while the pension and labor reforms advance in the shadow of the great corruption scandal of the Ungrd, and the retail legislative negotiation in Congress.

In the midst of this critical panorama, Petro launched his confusing proposal for a constituent assembly. “He has been changing the discourse. First the Assembly, then the constituent power, whatever. But foreign investors don’t understand that, and they say: ‘here is a discussion about a substantial change in the rules of the game,’” says Mejía of Fedesarrollo. “The president is very symbolic, but they generate uncertainty because people see them as a leap into the void,” adds Guevara, from La Nacional.

The relationship with the private sector: with cocoas, but without unions or SMEs

If anything remains of the national agreement with businessmen, they are some projects with the great rich of Colombia that began in a highly publicized meeting in Cartagena. The so-called cocoas, such as Luis Carlos Sarmiento Angulo, and some businessmen from the Valley, have modest cooperation projects, and a direct line with Laura Sarabia, Petro’s right-hand woman.

Others feel isolated and unprotected. “Cocoas are economic structures that may do poorly in Colombia, but they have investments that help them dilute the risks. We SME owners don’t have that,” says Ways, who owns a medium-sized processed food business in the Caribbean.

On the other hand, from the large unions, such as Andi and sectors of the Guild Council, they see a broken dialogue. “The tripartite dialogue was broken since the presentation of the first labor reform, and that is very serious, because it is a commitment before the ILO,” says Mac Master, who is also president of the Trade Council, the largest union of trades in the country. .

Furthermore, as the government has advanced, the president has been losing key interlocutors. Ocampo, despite being pointed out by the private sector as the person responsible for a reform that hit businessmen and investment, was an interlocutor with a great reputation. Cecilia López, former Minister of Agriculture, also had ties and credibility. Jorge Iván González was seen as a sensible voice at the head of the National Planning Department. And Germán Umaña, at MinComercio, had managed to strengthen ties with exporters. None of them are there anymore, and their replacements are less technical or more activists, and they all have less experience.

Fear of how insecurity is faced

Security has not been good since the previous government of Iván Duque. However, according to the view of actors in the private sector, two things have changed.

On the one hand, “everyone tries not to say it, but there was a selective application of the security apparatus, particularly the military. With a look based on the country’s strategic assets, such as logistics corridors, infrastructure networks, sugar mills, and mines. And that, in my view for the better, changed,” says Jorge Restrepo, economist and director of Cerac, an organization that monitors the armed conflict.

An example is what is happening in the largest gold mine in Colombia, in Buriticá, Antioquia, where since the arrival of the new government, illegal groups linked to the Gulf Clan have gained ground, as reported in this report by La Silla Vacía. “There is a breakdown of the links between the private sector and the security forces,” he adds. Reina, for her part, points out the increase in extortion as another facet of this phenomenon.

Colfecar, one of the most important freight transport unions, has denounced that, so far this year, road blockages have cost the sector 1.1 billion pesos, a product, among other reasons, of the increase in insecurity on the roads.

The second change that came with the Petro government has to do with the peace negotiations with the ELN and the FARC dissidents. “In the Santos negotiation the red lines were always very clear, especially a key one, which has to do with security policy,” says Restrepo. Now, however, in the government’s negotiation tactics there are no such lines, everything is subject to negotiation, as was seen with the comings and goings of the ELN participation agreement, where the most critical sector was the private sector.