Jilberto Zamora, deputy director of the Theoretical and Experimental Center for Particle Physics at the Andrés Bello University (UNAB), is in Geneva, Switzerland. He left Chile on June 18 and plans to stay for six weeks. The trip is ostensibly for work, because the doctor in Physics is working at CERN (European Organization for Nuclear Research), the great international scientific center dedicated to research in particle physics. But those who know him know that it is also a visit for pure pleasure.

“If there is one thing that everyone complains about, it is that I am a workaholic. I don’t know how to explain it. I can’t give an operational definition, but I can tell you how it feels. I can’t imagine life without science, I get bored, I tell you this in a very honest way. When I say that I am a workaholic, I don’t do it with regret, no. I say it because I enjoy it. I love what I do,” says the doctor in Physics.

This passion dates back to his first years of school. “I have always liked physics. I liked it since first grade,” she says. But why particle physics? “Because it is the most fundamental area. I mean, Particle physics is the area that studies the most basic constituents of nature, the branch that studies the bricks of which the universe is made,” he explains.

Trying to unravel the mysteries behind these elemental constituents, he went to Russia to do a postdoctoral fellowship at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research, where he began to get more involved in experimental issues. He returned to the Faculty of Exact Sciences at UNAB, which had defined in its strategic plan the creation of the experimental physics line. Then UNAB joined the Federico Santa María Technical University, where Zamora had done his undergraduate degree, which had begun the history of collaboration with CERN.

“In some way we all got involved, we could say that it was a family legacy,” exemplifies Zamora.

These universities, together with the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile and the University of La Serena, converged on the Millennium Institute of Subatomic Physics at the High Energy Frontier, SAPHIR, where work is carried out on all the sciences associated with CERN and where Zamora also participates as an associate researcher.

“At the Institute we manufacture hardware for CERN, such as electronic boards, detector parts, etc. But the SAPHIR laboratories are UNAB laboratories. I believe that 98% of all the equipment belongs to the university. So in some way there is a symbiosis between the two,” explains the UNAB academic.

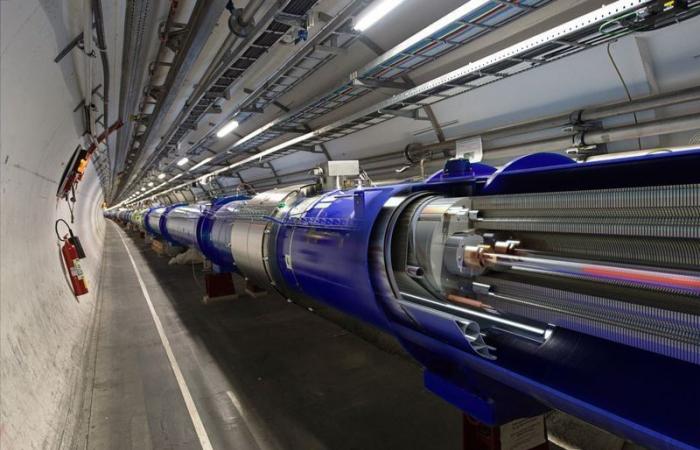

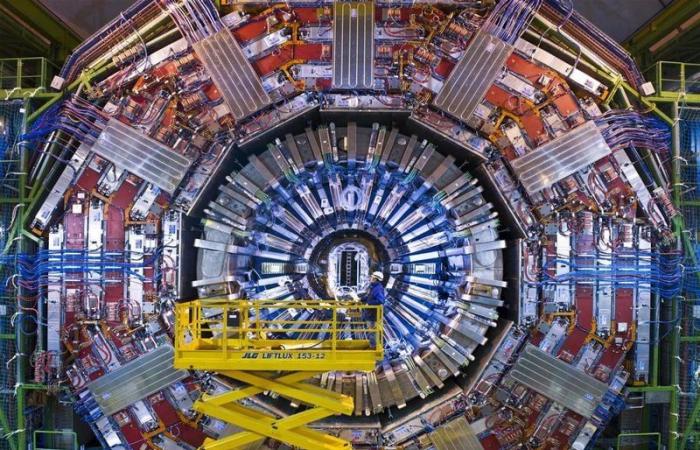

CERN is important both in infrastructure and scientific impact. It occupies a large campus with numerous facilities, including the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), which is the largest and most powerful particle accelerator in the world, with a ring 27 kilometres in circumference.

In addition, it has a global network of thousands of scientists and technicians collaborating on advanced research projects, which underlines its importance and magnitude in the international scientific community. “The Vatican is to Catholics what CERN is to particle physicists,” explains the UNAB academic

Currently, nine Chilean researchers, in addition to Jilberto Zamora, work at CERN as users, and although this represents a major advance for national science, they do not have access to all the benefits that the research center offers.

“Being a user means that you have access to certain infrastructure, you can use some things, but at a basic level, that is, you can participate in experiments, do data analysis, contribute with hardware, etc. But limited, let’s say. There are many benefits that you don’t have. For example, there are certain scholarships for students that you can’t apply for and contracts for professionals that you don’t have access to, which is fair because your country isn’t putting up the money,” says Zamora.

In July 2023, President Gabriel Boric requested CERN to grant Chile Associate State status. To achieve this, the country would have to provide funding that would be used for the same research carried out by Chileans. Among the benefits is that the Chilean industry could participate in tenders. Zamora gives an example: “A Chilean SME that is capable of manufacturing specialized cables. Perhaps it is interested, it does it, it does it well and it also allows it to enter this high-tech market.”

Just last March, a delegation from CERN visited the country to analyze whether it qualifies to enter the big leagues of global science.

“They visited our infrastructure, they were at Andrés Bello University, they saw the laboratories and the things we do now,” says the academic. When the top management of the research center meets, it will be decided whether to approve or reject the proposal. And if the response is favorable – Professor Zamora believes it will be – it must then be ratified by the national Congress.

During his time at CERN, which will last until the end of July, Jilberto Zamora is making the most of his time. His agenda abounds with collaboration meetings, about the experiments in which he is participating. He comes to finish pending things, to work with colleagues on the investigations that are carried out together.

The academic enjoys his stay. “When you do particle physics, particularly experimental, things happen here. In other words, it is the largest accelerator in the world. It’s great. “It’s being in the right place.” it states.

The UNAB academic participates in three experiments at the research center. The first of them is NA-64, which seeks to see dark matter for the first time. Astronomical observations suggest that there is a certain type of matter that cannot be seen with telescopes and that scientists hope to find because it would explain several astronomical phenomena that still have no answers.

The second experiment, called SND, studies the interaction of neutrinos, which are very special neutral particles produced in a collision in the Large Hadron Collider (LHC). The main objective is to analyze the interaction of these neutrinos with atomic nuclei, an issue that is a very unexplored field, according to Professor Zamora. The third is the giant and renowned ATLAS experiment, which discovered the Higgs boson.

“Apart from classes, all my activities at UNAB, or almost all of them, are projects that in one way or another have to do with CERN, so everything I do is linked to this. I have undergraduate students, PhD students, I have postdocs. All these people are linked to different projects that are related. Balancing that is a lot of work. I work about 14 hours a day, seven days a week. But it doesn’t weigh on me as if I had to work 14 hours doing something else. I couldn’t. Because I like this so much, time goes by quickly,” she concludes.