Everything was delayed. The guards and other prison officials looked upset and nervous. Someone was raising their voice, the words were dry, cutting. A heavy tension. Nobody imagined it would be so difficult. They had taken the precaution of doing it very early, at dawn. So that the witnesses were few. They thought it would be something quick.

But they were wrong.

They assumed that, as they had done several times, previous experience would smooth out some practical issues.

But they were wrong. They were convinced that it would be the same as on other occasions.

But they were wrong.

Someone, frustrated, threw one of the cables to the floor; another stood in front of the murderous device trying to think how to solve the problem.

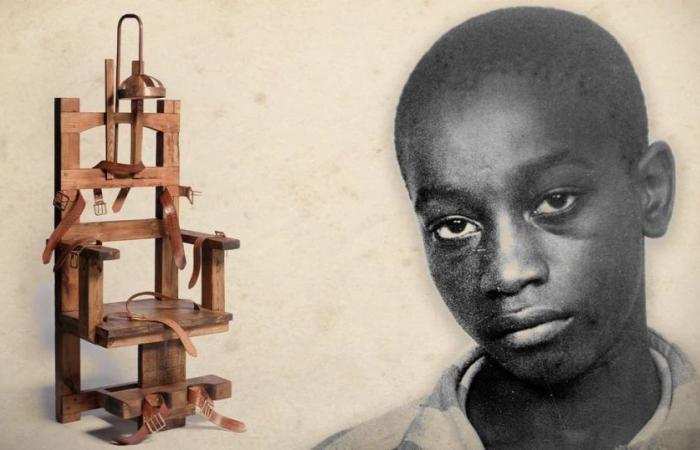

The condemned man was so young, not only in age, that the electric chair did not work. He was less than five feet tall and weighed 43 kilos.

Perhaps one of the executioners remembered a common scene in hair salons of the time. When a boy went to get a haircut, so that it would not be buried in the huge, deep barber chairs, they were made to sit on a stack of magazines or on two or three telephone directories: this way their head was above the backrest and the hairdresser could do his job well.

They brought from the prison director’s office the thickest books they could find: in prisons the books with the most pages are always Bibles. So They stacked two Bibles on the electric chair and sat the 14-year-old boy on them. Only at that moment, the executioner breathed a sigh of relief. He was going to be able to kill him in peace.

George Stinney was executed by electric chair on June 16, 1944, 80 years ago. He was a 14 year old boy. He was a 14-year-old black boy.

The racial data, the distinction of the color of their skin, is essential to understand this story.

George Stinney still has an atrocious record: he is the youngest person to be executed in the last century in the United States.

On March 23, 1944, two girls disappeared in Alcolu, a small town in South Carolina. Bety June Binicker was 11 years old and Mary Emma Thames had turned 7 the week before. They had gone out for a bike ride; They wanted to collect flowers. Hours later her mother began to worry. They did not return and nothing was known about them. The whole town began to look for them. Despite being in a place where the racial barrier was ironclad, almost insurmountable, there were no color distinctions in the people who went out to track the girls. Many patrols were formed. Among them was George Stinney Sr., who worked in the city sawmill and had 4 children; He had given the oldest one his own name.

Many hours later they found the bodies of the two girls. They were dead. They had smashed their skulls with blows. A steel bar, a piece of trunk, some blunt and heavy object that was unloaded on their heads, viciously and very violently, several times. Hours later, a discovery seemed to solve the issue of the murder weapon: they found, lying among some bushes, a bloody piece of railway sleeper.

They just needed to find the person responsible. The pain and indignation of Alcolu society added pressure to the investigators. Two white girls attacked while riding a bicycle whose bodies were found in the black zone of society, in one of the poor neighborhoods where the colored population lived.

Investigators needed to find someone responsible as soon as possible. And, for them, the search was only limited to people of color.

George Stinney Jr., the 14-year-old boy, while the whole town was looking for the girls, had said that he had seen them pass by that morning. and indicated that they were heading towards the area where they were finally found.

That statement, that comment, was enough for the researchers, in the absence of a better candidate, They would point him out as the culprit.

They went to the humble home where the family lived. The police entered shouting and drawing weapons. Her younger sister, frightened, hid where her family’s cow was resting: she feared that they would take her too. George didn’t understand what was happening. He swore to them that he had done nothing.

They arrested him and left him incommunicado despite the despair of his parents. who asked to see it. What happened during those interrogations is a matter of speculation. After many hours an investigator came out proudly saying that he had obtained a confession.

He said the boy admitted to having murdered the two girls. The truth was that since he was arrested, George could not be seen by his parents or a defense lawyer. The interrogation lasted many hours. They pressured him, they hit him, they tortured him until, supposedly, he confessed.

Meanwhile, the father was kicked out of the sawmill and the family, threatened, had to leave the city.

The trial was set up very quickly. Within days George Stinney was seated in a courtroom in front of the judge, the prosecutor and a jury. All men. All white men. In the room and surrounding the building more than a thousand white people gathered to follow the events.

Since his parents did not have greater economic resources, George was assigned an official defender. The lawyer carried out the task with evident apathy, as if it were a heavy obligation, an uncomfortable procedure. He did not even call witnesses on his behalf. And he refrained from questioning those called by the prosecution. Such negligence can only lead one to assume that he was convinced of the guilt of his client (the his client is just a euphemism) or he was convinced that nothing he did would be fruitful, that condemnation was inevitable due to social pressure.

The trial took place at an unusual speed. The selection of the jury members, the opening words of the parties, the witnesses, the expert evidence and the arguments of the prosecution and the defense took no more than 5 hours. The jury retired to deliberate. But the room remained empty for less than 10 minutes. It was immediately known that they had reached a unanimous verdict: No one was surprised when the jury foreman reported that George Stinney had been found guilty.

Before deciding on the sentence, the judge explained, he recalled, that For South Carolina law, being 14 years old was equivalent to being an adult and that the convicted person was subject to the same sanctions as an adult, regardless of the severity, the irreversibility, of the sentence imposed. He then announced his decision: death sentence.

George Stinney had to wait his last day on Death Row.

But no one trusted that the decision would be reversed. Nobody protested either. The white population of the town and the local newspaper were satisfied with the decision. Finding a culprit and having him receive the worst punishment helped to get through the pain. George had to be moved to another prison because a mob tried to lynch him and set fire to his place of detention.

George, crying, told his cellmate that he had not killed them, He couldn’t understand why he was in that situation.

Less than a week after the conviction and the imposition of the capital sentence, Hooded men in white, belonging to the Ku Klux Klan, burned several houses and killed three black men. The perpetrators of these murders were not arrested by the police, nor pursued by justice.

From the moment of sentencing to execution – there was not even a half-hearted appeal in between – the 14-year-old waited 53 days. With the formal legal proceedings over, he only had one chance to save himself. Governor Olin Johnston’s pardon, which at the last minute could transform the death penalty into a life sentence. But the man, a politician more interested in satisfying his electorate than in being pious, said he had nothing to do: “If the penal system imposed that punishment on him, it must be for a reason,” he declared. There was no mercy for George.

George Stinney was executed on June 16, 1944.at dawn, in an electric chair that was too big for him and sitting on two Bibles.

The news appeared in the newspapers and the majority of the columnists and also the (white) population of South Carolina agreed with his execution. They said that this would eliminate a problem and would serve as an example for people of color who might want to break the law in the future.

Sixty years later, George Stinney became more than just a record or a story to which the newspapers dedicated a note on each round anniversary.

A group of people demanded the case be unfiled and asked that the case be reviewed. Some were ironic about the issue. They sarcastically asked if in this instance of review the judge had the power to resurrect him if he was not convicted once again.

The case took 10 to reach the hands of the judge Carmen Tevis Mullen. George’s younger sister, now 77 years old, continued to push for the cause to be studied again. In the new hearings, all the pages of the file were reviewed again, George’s surviving brothers and several of the people who made up the 1944 search patrol were questioned.

In this instance, seventy years after the execution, The judge issued a new ruling. She claimed that the trial carried out in 1944 suffered from severe and insurmountable procedural errors. He was forceful: “I can’t remember a case in which there was so much evidence of violations of constitutional rights and in which so many injustices were committed against the accused.”

After his investigation he concluded that the police violated all procedural rules and that the confession he obtained is not proven other than by the statements of the officer who hit George. As if that were not enough, there are two different versions of the confession in the file: the police officers could not agree on the story that the officer in charge of the interrogation had supposedly told them. The confession does not appear in any writing, it was not recorded in any minutes).

If he did not have a lawyer during the police interrogation, in the brief oral trial, although there was formally someone designated to defend him, “in that instance the lawyer did little and nothing to defend him,” he noted in the sentence. And he discovered, several decades later, that The official defender had never practiced criminal law: he was a specialist in tax law.

Judge Carmen Tevis Mullen determined that George Stinney was not guilty, that despite the time that had passed, it was clear that there was no evidence that pointed him out.

And at the end of the sentence that repaired, at least, the George Stinney story, the magistrate stated: “In my long time in justice I have never seen a case so poorly investigated. “Never in my judicial life have I witnessed a greater injustice.”