Every quote, Mieke Bal argues, is situated at the intersection between iconography and intertextuality. A visual work is cited as a text is cited, promoting an encounter between two elements that is always a crossing between two times. Although maybe it’s the … Baroque is the period in which the quote becomes more evident, this allegorical procedure can be traced in the History of Art from its beginnings. To quote is to take advantage of an impulse, a dynamic, but it is also a way of showing the cards, showing that every work, every speech, comes from a previous conversation, a dialogue that is established beyond space and time.

The way in which Ramón Gaya pays tribute to Velázquez has a lot to do with this sense of the quote understood as a conversation. In his painting, Velázquez’s work breaks away from its concrete temporality and becomes present. It is not in the past, in the 17th century, but is part of the visual and emotional landscape of the Murcian painter. The prints, postcards, fragments of paintings or illustrations from books about Velázquez that appear in his paintings coexist with the artist, they are elements of his daily life.

Gaya’s painting is about feeling, emotion, reality and truth. But it is also about the painting itself. Gaya dialogues with the world close to him, and in that world the history of painting itself takes on a fundamental role. Hence we always find those constant references to other works that transform many of her paintings into meta-paintings. Some “meta-images”, as WJT Mitchell would call them, that Gaya uses to pay homage to Velázquez and that, if you think about it, actually allude to memory. In the background, the postcards of Las Meninas, the illustrations of the Villa Medicis, the fragments themselves drawn inside… indicate an important relationship with the memory of the royal work. They generate a connection between what is represented and the first referent, in this case Velázquez, who seems to be in memory, almost as if it were a repository, a pictorial archive. It is the literal meaning of the term souvenir, a memory, the opening in the memory of a path towards reality. That seems to be the meaning that also operates in the postcards and reproductions that Gaya introduces inside many of his tributes.

It is not Velázquez who influences Gaya, but the other way around: it is Gaya who transforms Velázquez

This is how we can understand, for example, a painting like ‘Mirror and Flower by Cardese’, from 1939, the first work in which a reference to ‘Las Meninas’ appears through a postcard in which we sense the masterpiece of Velazquez. In the painting, painted shortly after the unfortunate experience in the Saint-Cyprien concentration camp and the tragic death of his wife, the allusion to Velázquez’s painting serves to gain momentum, to lift the painting itself. The ‘Las Meninas’ postcard that appears represented in the image accompanied Gaya during the fateful days of his escape from Spain, and was even the only object that he kept in the refugee camp. Perhaps he used it as consolation, but also as a memory of painting in the midst of barbarism. Painting as salvation.

It is curious that this reproduction, which had resisted so much, was blown away by the wind just after finishing the painting and the artist could never recover it again. The object was lost, but the image remained, it infiltrated Gaya’s painting. And we can say that he never moved from there. The influence of Velázquez, his presence and especially his memory.

This constant presence of Velázquez’s work in Gaya, in his painting and in his artistic thought, has been treated with diligence on more than one occasion. This exhibition precisely tries to account for that invisible thread that unites the work of the two artists. But usually, and quite logically, the usual formula for presenting this relationship has been that of influence. Velázquez influences Gaya. However, we could try to turn it around. It is not Velázquez who influences Gaya, but the other way around: it is Gaya who transforms Velázquez, who makes us see and read him differently.

In ‘Quotting Caravaggio: Contemporary Art, Preposterous History’, Mieke Bal proposes this deranged sense of history. We must break the linear causality of history and understand that the works are not anchored to a specific time, but rather travel through it. Gaya’s Velázquez, for example, is not the Velázquez of the 17th century, but the Velázquez of his contemporaneity, the one that the artist contemplates in the Prado, the one who transforms it, the one who shares a time, a space and a vision. of the world. In that sense, Velázquez and Gaya are contemporaries. And in that same sense, Gaya is capable of influencing Velázquez. To transform the way in which, based on his painting, we look at the Sevillian master.

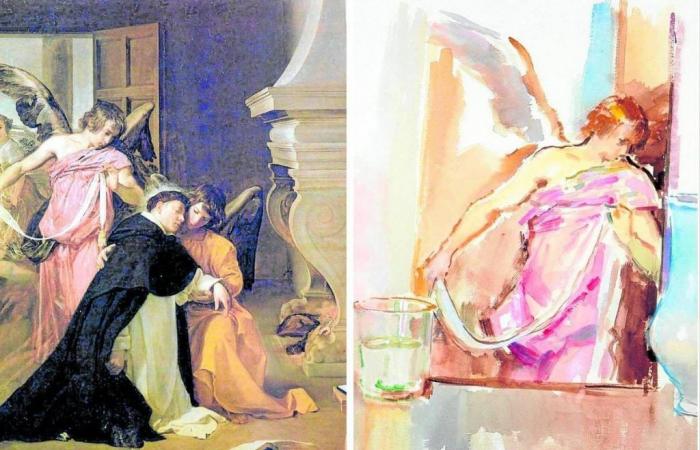

This is how I would like to read this exhibition, with this altered sense of time. Because Gaya’s tributes and quotes to Velázquez do not leave him immobile, but rather transmute him. When, in this context, one approaches that masterpiece that is ‘The Temptation of Saint Thomas Aquinas’, one no longer sees only the painting painted in 1632, with its original meaning, as conceived by Velázquez. Seeing him today, our gaze is conditioned by Gaya’s vision.

This is how I observe the still life in the foreground, the smoking firebrand, the books on the floor, the inkwell, the stool. He is, without a doubt, a Gaya. The background scene is also a Gaya, the woman who gets lost escaping through one of those doors through which the light enters in Gaya’s watercolors, doors and windows that open the representation and send the gaze outside. And, of course, the vaporous corporality of the figures, their lightness, the flight of the fabrics, as if nothing weighed, as if the air were capable of elevating each element of the composition, is also a Gaya.

Without a doubt, after Gaya – his paintings, but also his essays – it is no longer possible to see Velázquez in the same way. The ‘Lonely Bird’ that Gaya imagines is his own Velázquez, which does not exactly coincide with the Velázquez of Art History, the one that we historians often try to place unsuccessfully in the period. Velázquez de Gaya is not the baroque painter, but he is the eternal painter. The one who, rather than talking about a specific time, talks about a time that alludes to all the others. This is how Gaya feels about Velázquez, solitary bird, practically like a contemporary, like someone capable of transcending the era and speaking something that is outside of time.

In ‘A handful of arrows’, María Gainza writes that “a place belongs forever to the one who claims it most strongly, remembers it best, squeezes it, shapes it, loves it so radically that he reinvents it in his image.” Without a doubt, Velázquez’s territory belongs forever to Ramón Gaya. A Velázquez of his own, present, alive, capable of looking at the world through time.