María Blanchard (Santander, 1881 – Paris, 1932) was an artist with “a room of her own,” as José Lebrelo, curator of the extensive retrospective, points out. Maria Blanchard. Painter despite cubismat the Picasso Museum in Malaga, which will be open to the public until September.

The curator, who has also been the artistic director of the aforementioned Malaga museum for years, points out that there are several reasons for holding an exhibition of this magnitude on María Blanchard – 90 works by the Cantabrian artist are brought together – and one of them has to do, without a doubt, with “the memory” and “the updating of the reality of the pictorial legacy she left behind”. The last large-scale exhibition dedicated to the artist was 12 years ago at the Museo Nacional de Arte Reina Sofía.

«The figure of María Blanchard has very interesting values and qualities in our days. She was a woman born in Santander, in a liberal and cultured family; but she left Spain very early and settled in Paris from 1909 onwards», he explains. The artist realised, according to the curator, that «if she wanted to be what she felt and what she intellectually believed her artistic career should be, to which she was dedicated, Spain was not the country in which to do so».

Speaking of the freedom in Paris, which attracted artists, intellectuals and cultural enthusiasts from all over Europe and also the USA, Gertrude Stein, a wealthy patron of Picasso and Matisse who arrived in Paris in 1903, used to say that she preferred to live in France because “the French are masters of their own lives.” Indeed, those breaths of fresh Parisian air were a wild attraction for many artists who wanted to find their place in the art world. Paris had a modern and avant-garde atmosphere that was very conducive to the development of an artistic career, which was what María Blanchard was looking for. There, in those spaces still full of artists dressed in Parisian misery, is where the Santander native aligned herself with the artistic elite of the moment.

Paris: Expatriate and not following any man

On what her life was like in Paris, Lebrelo alludes to the concepts of expatriate and alone. Two ideas used in the exhibition catalogue by Xon de Ros, a professor at the University of Oxford. “María Blanchard left her country, she somehow renounced her family and the security of the language, she did not have many economic means and, in addition, she did not go to Paris to accompany any other male artist, something that today we would consider sexist and that, however, was usual in other female artists of her time. She was not the partner of any artist, who were the ones who ruled in that environment of masculinity. She always defended her space and was dedicated to a Parisian life committed to and focused on art,” she points out.

The gallery owner Guillermo de Osma, in a conference at the Círculo Orellana, explained that María Blanchard “suffered a lot with her physique. She had a hump, a genetic malformation, which gave her a great physical disadvantage and a fact that, in some way, forced her to live a celibate life, and which was also the reason for sarcasm and whispering behind her back. She suffered, and that is something that is reflected in her art. Painting was always her refuge and she was completely committed to it. About this regret and the reflection of it in her works, Ramón Gómez de la Serna said that she “had a child’s look, a whispering look of a bird with sad joy”; while the poet José Bergamín remembers the image of her as “magical and suffering.”

Upon arriving in Paris, Maria Blanchard immersed herself in the atmosphere of Montparnasse, attending the gatherings of The Rotunda either The Dome. Immediately, he began to have a relationship with Juan Gris or Pablo Picasso, and enrolled at the Vitti Academy, founded by Cesare Vitti in Paris, coinciding there with the Spanish modernist Hermenegildo Anglada Camarasa as a teacher. “The women had their own space there, they entered without problems to work in that workshop environment and went to class,” explains Encina Villanueva, in the cycle of Women artists in the Prado.

There she met Angelina Beloff, a Russian artist and Diego Rivera’s partner who became one of her great friends, referring to the Cantabrian as “a painter of great talent.” Beloff recounts in her memoirs that she sympathized From the first moment: «I remember that on one occasion, even, in one of the towers of Notre Dame, we made a pact of friendship. Maria had suffered an accident when she was a child, she was deformed, she had a deviated spine and a hunch on her back. She had an admirable head and her beautiful eyes reflected a great intelligence. Her life in Paris was heroic, she had almost no money, she only received a small pension from a scholarship from her hometown.»

An opinion that was shared by a large part of his contemporaries. Rivera portrays her as humpback, “it rose just a little more than four feet from the ground. Of course, above his deformed body there was a beautiful head. Her hands were, also, the most beautiful hands I had ever seen.

A risky cubist painter (1913-1919)

View of one of the exhibition rooms. @Museo Picasso Málaga

View of one of the exhibition rooms. @Museo Picasso MálagaLebrelo, a great admirer of her work, highlights María Blanchard that “she was a brave woman who settled without knowing anyone in an unknown country, with few economic resources, but with things very clear in artistic aspects. She soon joined the group of the most radical and experimental artists, a small group that did things in a way that no one had done until then. This is how she became the most important woman painter of the cubist movement.

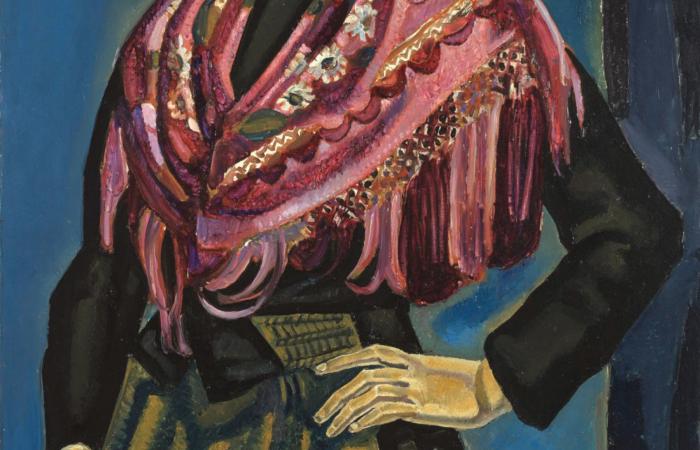

Notable works from this period include: The Lady with the Fana composition of traditional character made through overlapping planes, almost like a mosaic, where we differentiate the movement of the fan, made up of just three trapezoidal shapes in yellow.

His way of painting challenges the established order of the most academic compositions, a trend from which he is very far away, but which is to the taste of critics and the Spanish public in the early years of the. S XX. In 1915, María Blanchard exhibited in Madrid together with her great friend Diego Rivera, – who was in Spain with a scholarship from the Government of Veracruz in the studio of Eduardo Chicharro –, in the group exhibition organized by Gómez de la Serna: The complete painters, which received barbaric and very unpleasant reviews. “It was the first time that Cubist art was seen in Spain, the criticism was fierce and very negative,” comments De Osma in the aforementioned conference. María Blanchard would not exhibit again in Spain until 1943 in the rooms of the Biosca Gallery.

“Another element to place this artist in the memory of Art History is her singularity and the risk of her cubist compositions,” says Lebrero. «Although all that was not enough for her and in 1920 she abandoned this movement focused on still lifes or loaded themes with little existential weight, to make way for the third stage of her work: the figurative (1919-1932).

Return to the human figure

«He brings back the representation of human beings in his paintings. To be fair, we must also say that Cubism stopped selling well on the market and was no longer fashionable. And all this, of course, affected the artistic production of Cubist artists who also made a living from it. The economic factor also affected it, and we should not be afraid to talk about it», comments the curator. Nevertheless, and despite the fact that Cubist fever was dying out, works signed by male Cubist authors continued to be valued on the market, which is why unscrupulous art dealers erased their name from works by María Blanchard to put those by Juan Gris: «They were easier to sell and fetched a higher price».

In this exhibition at the Museo Picasso Málaga, the following stands out: The Bolognese (1922-1923), purchased by the Prado Museum, a work that portrays a fisherwoman in a festive costume from the Gallic region of Boulogne. The large white, starched cap that crowns her figure is striking, giving it solemnity and strength.

From her point of view, Lebrelo argues that with this new path, “María Blanchard became a great defender of values that are related to a certain feminine sensitivity. She, who was very advanced, liked to be close to brave women like her, although we are not talking about the music circles of Josephine Baker, who triumphed in the evenings of the Parisian cafés, or the circle of intellectuals and lesbians of Gertrude Stein and the American intellectuals, but of international and national thinkers, as was the case of Concha Espina.”

In fact, one of María Blanchard’s earliest works was owned by the writer: Nymphs chaining Silenus (1910), a painting for which she received the Second Class Medal at the National Exhibition of Fine Arts. Regarding this work, Villanueva relates an anecdote about it: «María arrived at the writer’s house, with a thin and somewhat anguished voice, saying: ‘Conchita, I have sent you this monstrosity so that you can keep it in the basement if by chance you have the key. If not, let the ragman take it.’ To which Concha Espina replied: ‘María, I have the key by chance, but the painting is beautiful and will not go to the basement. Don’t talk crazy things.’»

The presence of The Communicant

The Communicant, by Maria Blanchard. @Museo Reina Sofia

The Communicant, by Maria Blanchard. @Museo Reina SofiaOne of the works that is in the Picasso Museum Málaga is The Communicant (1914), a very special painting that he began to paint in 1914 and finished in 1920, exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants with critical and public success, and purchased by the famous art collector, Paul Rosenberg.

The canvas depicts a girl of First Communion which seems to be suspended in the air, next to a prie-dieu, an altar and a heavenly part, represented by four angels. «Today the First Communion It seems like a folkloric topic, but at that time it was something very important,” explains Lebrelo.

«This is a girl who was closer to adolescence and adulthood every day. He paints this communicant woman as stark and very different from the candidness of other representations. We know that Picasso also painted first communions, but they have neither the strength nor the existential charge of María Blanchard’s painting,” concludes the curator.

A woman with her own space

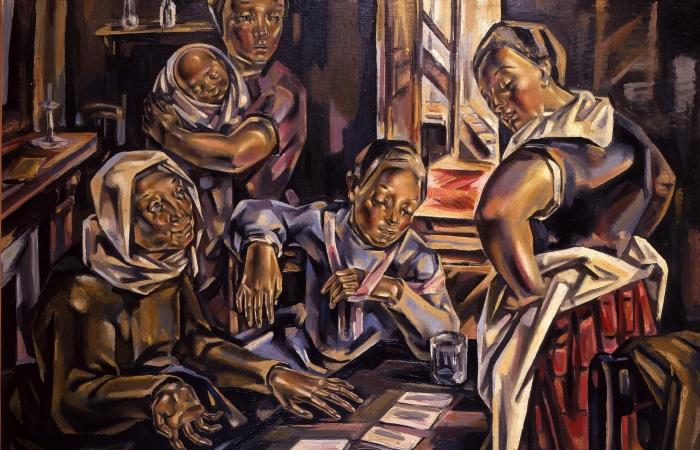

The Fortune Teller, 1924–1925, by Maria Blanchard. © Studio Monique Bernaz, Geneva

The Fortune Teller, 1924–1925, by Maria Blanchard. © Studio Monique Bernaz, GenevaFrom a personal point of view, apparently, Lebrelo relates, María Blanchard was “a woman who did not speak much in meetings, she was a person who tended to listen more. She would say that her paintings are the language she has to claim her own place. She represents that idea of A room of one’s own, by Virginia Woolf, that book where she said that women should have space and money to be able to write well. That also happens in Blanchard, although well, she didn’t have much money; but she does have that own room That is her art, and I would say that this is a characteristic of her. And it is there, in that space, where she develops a work that does not bend to fashions. She follows her own path and goes free.

She defends that she is “a woman who can be admired and looked at, who has independence and freedom, in a time period where women are only muses or companions, and used to paint secondary or decorative themes. “She paints migrants, old women or domestic spaces, where cooking, embroidery or taking care of children are the protagonists.”

In her later years, the commissioner recounts, Maria Blanchard “became very religious, she even wanted to be a nun, although she ultimately did not go through with it. I do not believe, however, that this return was to a stale or reactionary Catholicism, but rather a return to the spiritual and to the intimacy of the home as a space for quiet and reflection. A spirituality proper to a modern woman, not to someone who seeks God in the past.”

María Blanchard died of tuberculosis in 1932 in Paris, the French city that welcomed her and, above all, that understood her. An article from The Intransigent mentions the Cantabrian art, defining its art as “powerful, made of passionate love for the profession, one of the most authentic and significant of its time.”

@MaríaVillardón