Throughout his long life, Pablo Picasso always had the need to be accompanied by a poet. This fact even influenced the different stages of his creative universe because his friendship with certain authors also left a deep mark on the palette of the genius from Malaga. The list of these writers is long and includes such celebrated names as Apollinaire, Éluard, Cocteau and Alberti. Among all of them, Max Jacob undoubtedly stood out with special force.

The Musée d’Art Moderne in Céret has just opened an exhibition that allows us to discover a figure as fascinating as Jacob with his many and diverse facets. To this end, in addition to incorporating abundant original work and documents by the poet, some of them unpublished to date, We can also find pieces by several authors contemporary to this author, such as Juan Gris, Manolo Hugué, Jean Metzinger, Marie Laurencin, Jean Cocteau, Marie Vassilieff, Alice Halicka, Serge Férat, the Baroness of Oettingen and, of course, Pablo Picasso .

Max Jacob didn’t have it easy. Originally from a Jewish family, he eventually converted to Catholicism. His homosexuality tormented him on many occasions, as he was fascinated by having partners who were somewhat younger than him. He was also a man committed to his time, to the artistic renewal that was being experienced in Paris in the first decades of the last century. He, in this regard, was not a passive spectator but had an active role in translating into his literature the artistic cubism that could be seen in the canvases of Braque and Picasso. For this reason he wrote in 1917 that “cubism in painting is the art of working on the painting itself beyond what it represents.” […] do not proceed only by allusion to real life. Literary cubism does the same in literature, it only uses reality as a means and not as an end.

The creative call came early to the protagonist of the exhibition held in Céret because Max Jacob left his law studies to devote himself to art criticism in the pages of “Le Sourire de Alphonse Allais”, where he mainly studied the works of the Belgian expressionist painter James Ensor.

In 1901 he had a revelation when he entered an exhibition held in a Parisian gallery. It was the month of June and Jacob visited the dealer Ambroise Vollard’s room where the works of an unknown Spanish painter who was trying to make a living in France were hanging. That day he became fascinated by Picasso’s painting, whom he soon met to become one of his closest friends and supporters. The exhibition allows us to contemplate some of the numerous portraits that Jacob dedicated to Picasso, such as the one that shows the man from Malaga in the Place Pigalle in Paris. As a response to this friendship, “Nature morte au pichet sur le fond de chapeau de Max Jacob”, a Picasso composition from 1906, is also exhibited in Céret. Max Jacob was one of the first and most important supports that Picasso had while the latter He encouraged the poet not to neglect dedicating himself to the world of letters to the point of proclaiming: «You are a poet! Live as a poet! Jacob was one of the most prominent members of the so-called “bande à Picasso” which also included Guillaume Apollinaire, Manolo Hugué and André Salmon.

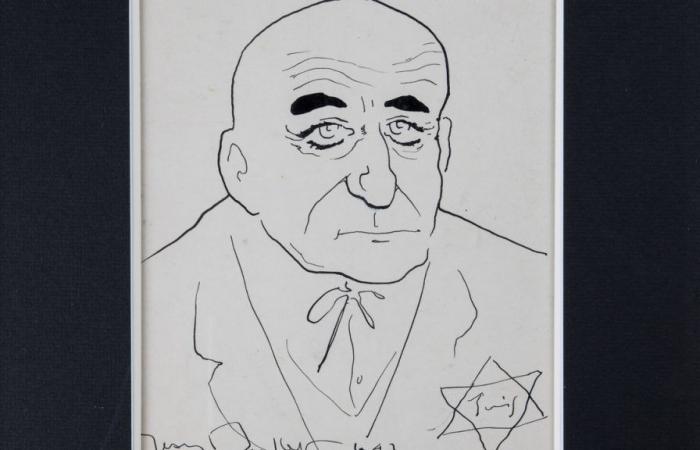

The exhibition also allows us to discover Max Jacob as a painter, probably one of his lesser-known facets, which can be seen in various inks and watercolours, including one that features a landscape of Céret. It was in this town that the poet met Picasso and his then partner Eva Gouel in April 1913. For Jacob, as he confessed in a letter to Apollinaire, Céret was a “pretty little town” where “the mountains seem to smell of thyme, dew, lavender and rosemary”. During those days, Max Jacob also took the opportunity to cross the border and visit Figueres and Girona, where he was fascinated by the sardana, as he demonstrated in the poem “Honneur de la sardane et de la tenora”. Throughout his journey, we can see that Jacob was at the centre of the Cubist universe, being himself the model for some of the most important names in the movement, such as Marie Laurencin, Celso Lagar and Jean Metzinger. He was also one of the promoters of the tribute dedicated to Georges Braque in January 1917, which he promoted together with Alice Halicka, Louis Marcoussis, the Baroness of Oettingen and Marie Vassilieff.

But this story ends badly because Max Jacob’s ending was terrible. In Nazi-occupied France, he was a sure bet to be one of the victims of that killing machine. The exhibition is taking place at the time of the eightieth anniversary of the death of the great poet in the Drancy concentration camp in 1944. Jacob had managed to elude the German authorities by hiding for a few months in the monastery of Saint-Benoit, where he was finally captured by the Gestapo.

For years it has been said that Picasso, who spent the Second World War in his workshop on the rue des Grands-Augustins in Paris unmolested by the Nazi hierarchs, could have done much to save the life of his beloved Max Jacob.

When it became known in the city of the Seine that the poet had been taken to the concentration camp, JSean Cocteau and Pierre Colle began collecting signatures with the naive intention of putting pressure on Jacob to be released. So they did not hesitate to go to Picasso’s studio to obtain his signature. They were unsuccessful because the man from Malaga did not want to have anything to do with the matter. Picasso was probably afraid that this gesture of solidarity would attract the attention of the Nazis. You will never know. The only thing that is certain is that he did not save Max Jacob and that that ending tortured him.