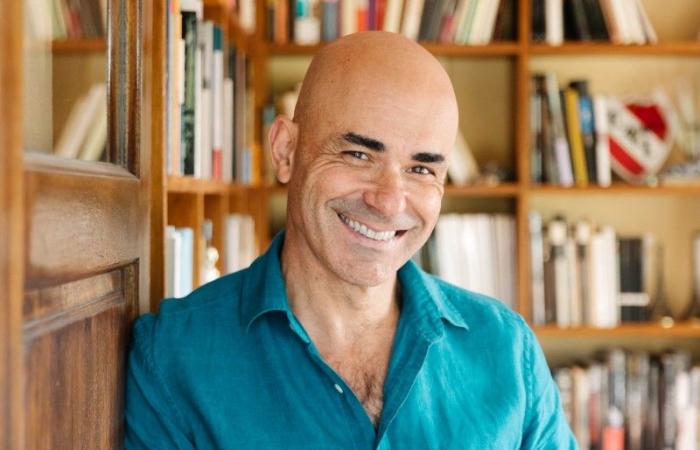

Paulo Menotti / Special for El Ciudadano

“My original plan, if such a thing existed, was only to write the first of the books, which was called “The Days of the Revolution.” But the publisher suggested that I internalize the matter, or extend it. And of course, out of concern I thought about the overall view, and I thought that the question could be expanded to the formation of Argentina as a Nation State in a perspective of a long 19th century, until 1916. How Argentina was built on various levels. That, thought of four books,” Eduardo Sacheri begins the interview when referring to his new book “The Days of Violence. A history of Argentina when it began to be Argentina (1820-1852)”, which he presented to booksellers last Thursday the 13th in Rosario. In dialogue with The citizenthe writer, film scriptwriter, history teacher and historian shared some concepts that characterize this text that addresses a conflictive, violent period in national history, in addition to referring to his interest in disseminating history, his profile as a narrator. and teacher, and his vision of history as a process of change.

Violent times

“In reference to the name of the books called “The Days of”, I needed to find a concept for the second one. I was between two ideas. One was “the days of the provinces”, based on the approach of José Carlos Chiaramonte, in the sense that since 1820 there has been nothing similar to a central State, what there is are provinces. The other was “violence” because it gave me the feeling that the revolutionary militarization and the economic disaster gave the political system of the period a very violent primitivism and a lot of exhibition of that violence. In this period, this acquires a semantic character in the sense that exercising violence, theatricalizing it, becomes a message. In a way of being politically linked in a stronger way than in the previous stage, and clearer than in the later stage,” Sacheri explains following the title of his second history book. The first, “The days of the Revolution. A history of Argentina when it was not Argentina (1806-1820)”, investigates the May Revolution and the War of Independence, while its second volume addresses the period of dissolution of the United Provinces and Rosismo.

The point, however, is that violence never ceased to exist, although the author reflects on why he chose that concept.

“Of course it is a hypothesis, but starting with Caseros, the following period 1852-1880 continues to be very violent; But as the national State emerges, I get the feeling that this violence tends to be regulated. Not to mention in the 1870s, when the Judiciary began to intervene in rebellions, etc. “This is about the theatricalization of what is done with the dead,” says Sacheri, giving as an example the execution of Chacho Peñaloza, which was bloodthirsty but which in the 1860s attracted attention unlike the exhibition that the Reinafé brothers received ( accused of murdering Facundo Quiroga in 1835) when their corpses were exposed for a long time in the Fort of Buenos Aires. “Or the Oribe bloodbath in 1841, 1842, touring the interior,” added the author.

Neither mitrists nor revisionists, neither good nor bad

Argentine historiography arose from the texts of Bartolomé Miter with his stories of Belgrano and San Martín from where the so-called “official history” or “mitrista” was forged that placed some characters from our past as heroes and condemned them to failure or death. place of villains to others, particularly the leaders. In the 1930s, “revisionism” emerged that condemned Miter’s views and restored leaders such as Juan Manuel de Rosas, among others. However, this new perspective did not come from the opposition of good and bad.

“I studied at the Faculty in the 1980s and 1990s, professorship and bachelor’s degree. What I learned in college was an overcoming of that and what I regret is that it does not pierce common sense on the public agenda. And by that I don’t just mean politicians, the media, but the shared common sense that has a vision and that seems inevitable and okay to me. It is true that the academic world logically has its internal dynamics, very internal and very little connected to the outside. Yes, something can be done with dissemination to connect that with that academic world. Put a new vision of history within the reach of people who do not have to know what Tulio Halperín Donghi, Hilda Sábato, José Carlos Chiaramonte, Marcela Ternavasio have written,” Sacheri explained and added: “That’s why I started to think that I have an audience created from the world of fiction and that gives me a certain visibility that would be good to disseminate this story.”

Tell it like a teacher

Upon entering “The Days of Violence,” the reader notices that the tone chosen by Sacheri is that of the professor giving a history class, with metaphors, with explanations, with a bearable narrative that many would have liked. have during your time at school.

“I still teach high school. I left university a long time ago. I reduced the hours I gave and was left with a few hours at a secondary school on Monday mornings. I do it because it is a part of my life that I value. I also recognize myself as a history teacher and I will never stop being one. It seems to me that it is a useful job for other people, although all jobs have their uses, and that it gives you a plus. I studied history because I found it valuable to share with others. And I discovered that I liked it,” Sacheri confessed, that he appreciates his teaching because he also helped him find the tone to write history books.

“For these books, I ended up discovering that the orality of the class is the only possible tone to write them.”

The stepping stone of disclosure

“Now I’m writing the third one. That’s why I’m reading what was written in the last ten years, because it’s been ten years since I left the Faculty. I’m doing the happy “state of the matter.” But when I start writing I know I’m going to find the same mess. When you write a novel, when you refine the tone you want to achieve for that novel, you maintain it,” explains the author.

Sacheri confessed that he feels more comfortable writing novels than about history, because in the second the issue is more complex.

“As for history books, it is not easy, because you start writing and, of course, you are faced with complex problems. So you get complex and write a paper, but you realize that no one is going to understand it, no one is going to enjoy it. The idea is that there has to be enjoyment for the general public,” warns the professor when he points out that he feels in a pivotal situation where the history dissemination text has to be entertaining but serious, and with the most up-to-date information. It is discussed in the academic field at the same time.

“That’s why I tell myself, this has to be entertaining, fun and I think, I’m becoming a fool. Someone from the academic world takes it and says it’s nonsense. So, the orality of the class ends up being the most correct because in school you make topics available to students and you accompany them to the complexity of them. I do it in a pendulum way because I take you but when I feel that you are getting lost I slow down a little, and then I return.”

“That has to be disclosure. A step of communication between academics and the outside world. Like a transmission belt at the same time pleasant to read and complex from knowledge. I say it and it sounds very nice but it is difficult,” the author completes the idea.

anachronism series

In recent years, television or streaming series have appeared that are period and seek to include people of color or provide women with spaces of power that they did not have at that time. Sacheri expressed that she opposes this idea because they show an anachronism of something that did not happen and that they erase the change, they sweep under the rug the struggles to have a world where racism does not exist and where women enjoy rights like men.

“Audiovisuals are poorly approaching the past because they are offering an anachronistic view of the past. It drives me crazy,” Sacheri confessed.

“There is a discomfort in accepting that the past was different from the present and that seems extremely dangerous to me as a symptom of these times. We don’t need to rewrite the past, we need to understand it. What we need to write is the future, with what we decide to do with humanity. Furthermore, this rewriting of the past erases the notion of change that is essential to history. And it erases what human beings have worked hard to change. If it now turns out that the English nobility of the 18th century is full of blacks and full of women in very important roles in all areas, we erase the fact that it was an absolutely sexist and racist society. If it is not today, let us celebrate that we have a more diverse and horizontal society and accept that societies changed because people decided that they had to change. Because it will continue to change,” Sacheri attacked that anachronistic perspective on history.

“This mythical thing that we live in a definitive society is a very totalitarian notion. All totalitarianism is based on the feeling that the end of a path is felt as the perfection of something. And that is not right and I purposely use the totalitarian concept even though it sounds strong. But if you consider yourself the end of a process of change, the peak of where a society can reach. That is not happening nor will it happen. Things are going to continue to change and we have to be careful where we want to go. If I say that the past has no changes and neither does the future, I take away people’s emotional and rational tools to make changes or to be able to see directions. Studying history involves comparison, just like other social studies. Distorting the past to reduce comparative tension is a bad idea for me,” Sacheri concluded.

Book details

Name: The days of violence. A history of Argentina when it began to be Argentina (1820 – 1852)

Author: Eduardo Sacheri

Editorial: Alfaguara