Some will think that there is something arbitrary in including, among the vast list of poets and poems forgotten by the prosaic cruelty of these days, a writer who obtained his just recognition in admirable narratives, essays and translations.

The truth is that Marcelo Cohen (1951-2022), author of novels such as Insomnio (1986) and Ojaral’s Testament (1995), of the stories of The End of the Same (1992), of essays such as Really Fantastic (2001) and creator of the singular universe of the Panoramic Delta, translator of Shakespeare and Raymond Rousell, of JG Ballard and Clarice Lispector, he not only cultivated, like so many, the confessional and painful verse of adolescence. He also built his fictions from a poetic vocation that, far from being ornamental, contributes to missing the already rarefied air of the stories unfolded, through an always new breath, sustained in surreptitious rhythms, unexpected adjectives and happy neologisms, which in many cases make language another protagonist of the narrative. It is not necessary to delve very deeply into Cohen’s novels and stories to come across moments in which poetry bursts in, not to color what is narrated with hints of refinement but as a way of coagulating meanings or installing the reader in an emotional dimension of the experience, with the economy of the shortcut or the diver’s impulse that only the poetic word can exert. See: “The sky does not look like the sky but rather the roof of a great cavern. Low and still, from edge to edge it is the color of tungsten, and from the swings of the fog it obtains false streaks of humidity, stains of amnesia and mistake. The sky hangs over the sea, weighs it down, clouds it, not out of ill will but because the fog and the incandescent air, dazed emissaries, have abandoned themselves to the weight of a greater illness” (“The Monarch Illusion”).

In any case, we must not forget, either, Cohen’s hospitality towards the poetry of others. On the one hand, in his careful and necessary translations – his magnificent translation of Wallace Stevens’ Adagia (Interzona), or his versions of Shakespeare (Norma), for example. And, on the other, in his generosity to review or present other people’s poetry books. Whoever writes this can give personal and grateful testimony of the latter.

Authoritarians don’t like this

The practice of professional and critical journalism is a fundamental pillar of democracy. That is why it bothers those who believe they are the owners of the truth.

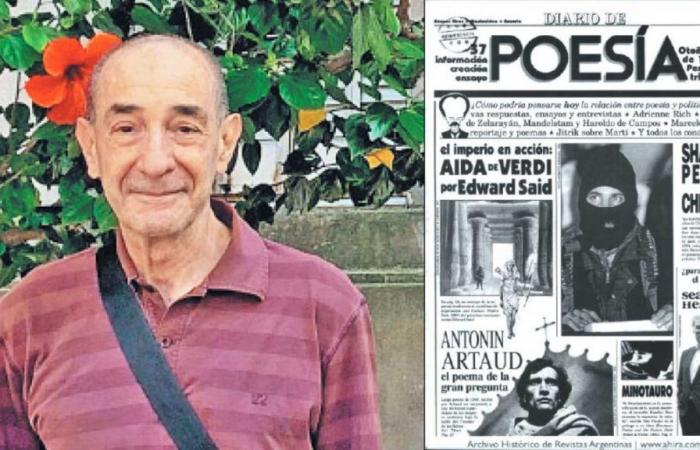

But also, in a manner biased towards his unavoidable narrative and essay production and as a translator, Cohen continued to write sporadic poems, with long verses, deceptively free and loaded with the rhythmic subtleties of a very fine ear and the speculations of a delicate imagination. In fact, in number 37 of Diario de Poesía, published in April 1996, along with an interview that Cohen had with Daniel Freidemberg, DG Helder and Daniel Samoilovich, two substantial poems of his until then unpublished are published: “Gestures during goodbyes ” and “Satellite”.

In that talk, Cohen shares reflections on poetry that deserve attention: “Every time you read a great poem you are less afraid of death. Poetry is the great therapy. Because he treats death like he treats life,” she says. And, later: “Poetry allows us to see, suspending the proliferation of thought. (…) The emotional power of poetry has to do with what the world gives at the moment when the world is in danger, knowing that the world is always in danger for everyone.”

In 1970, that is, twenty-six years before those statements and those poems, Marcelo Cohen, nineteen years old and reluctantly active in the Communist Party, attended the Aníbal Ponce literary workshop at the IFT Theater, coordinated by the PC. Some of his colleagues from then, who would later continue with him in the remembered workshop of Mario Jorge De Lellis, are: Daniel Freidemberg, Alicia Genovese, Rubén Reches, Irene Gruss, Jorge Aulicino and an intermittent and today unlikely Jorge Asís.

“Marcelo was the first person I made contact with when I entered the Aníbal Ponce workshop,” Freidemberg tells me now. “I remember reading a poem and Marcelo told me: ‘Ah, it looks like you’re a Gelman reader.’ I was very happy to meet another Gelman reader. Shortly after, already in De Lellis’s workshop, we shared a few more years. Marcelo wrote poetry in those years, yes. In fact, we all did it, although he to a lesser extent than the rest, because he was already emerging as a storyteller and was about to publish his first book of stories: “What remains.” And, although almost all of us probably wrote nonsense, we already had high esteem for the literary quality of the texts. Marcelo was, in that sense, a great mobilizer. One day he brought Eliot’s Four Quartets to the workshop and, for us, it was a shock.”

In 1970, as already mentioned, when he frequented the Aníbal Ponce workshop and still did not decide to pour his poetic quality into the narrative to shape it like few others, Cohen published this fresh and luminous poem, titled “Manolo”, in number 5 of the today unfindable magazine Suburbio, which I found, as a gift of chance, shortly after Marcelo’s death, in the study of the psychoanalyst and former bookseller Abel Langer, while I was interviewing him:

The wise man tells as it is said

[de la calle

que no tenía nacimiento.

A veces, sí,

se apreciaba de un vientre

[triste,

una madre invernal y

[preguntona,

el hogar, los libros, un

[hermano.

Venía de más atrás de las

[cosas

perdido en un camino marrón

con mesas y poemas y

[lagañas.

Tenía una lágrima en los

[dientes,

una mentira caprichosa,

la alegre fanfarronería del

[alegre,

la moneda triste del no puedo.

Una vez casi se muere:

quedó robado entre los

[muslos

de una mujer que hacía el

[amor

como en el agua.

Después

tuvo vergüenza,

sus piernas caminaron sin

[mirarse.

Pero no pidió ni un cigarrillo

[solidario,

aguantó solo toda la lluvia de

[la noche.

A la mañana ya reía

[nuevamente.

Pensó que estaba vivo

y se fue a lavar la cara.

No más pruebas, su señoría. Vaya uno a saber cuántos otros hermosos versos de Marcelo Cohen esperan agazapados en alguna isla secreta del Delta Panorámico.