In El Desconcert we publish this account of a historical interview, a piece of journalism memory. It is the journalist Jaime Gré who remembers how, in the early 90’s, he was able to interview the wanted boss of Lautaro, Guillermo Ossandón, no less than twice.

Twice in less than a year we interviewed the head of Lautaro, Guillermo Ossandónalias Diego Carvajal. A lot of checking and counter checking, tinted glasses at night, a lot of hood, safety equipment and weapons (short and long) to finally achieve several hours of exclusive interviews that made the police and the government of the time very nervous.

These were the first years of the recovery of democracy and There was still a lot of activity from some armed groupswhose actions we followed for journalistic purposes from the magazine Open Page. From the remains of MIR military there was almost nothing left, and of the Autonomous Patriotic Front we had enough information, but we knew very little about the Lautaro Youth Movement.

From Open Page We decided to accentuate its monitoring by looking for non-open sources, more direct sources close to the group. The idea was to interview his top boss, Guillermo Ossandón, so that he could explain the reasons and purposes of his actions.. It was not an easy task since Ossandón had never given an interview to any media, neither national nor foreign. And that task fell to the person who signs this note.

I started talking to some old contacts from the MIR and others from the MAPU who gave me some guidance and interpretations. But she was an old friend of Pedagogical Institute (where I had studied journalism in the late 60s and early 70s) which began to open the doors to the group for me.

They began to send me propaganda material (pamphlets, magazines and videos) with which I wrote a couple of articles – as neutral as possible – in August 1991, not an easy thing in the magazine since our editorial line was clearly against armed groups of any kind..

And the first appreciations came from Lautaro. They told us that we were objective since we did not disqualify them and we provided truthful information about their actions. The strategy was working, since the idea was with that floor to ask for an interview with the boss. So I did it. The typical preparations began (dates, conditions, guidelines, etc.) but not much progress was made.

Then I decided to change the strategy and suggested to them that perhaps before leaving it was better to speak with an important leader, but not with the boss of bosses. So it was. We had a long conversation in a restaurant in Plaza Italia with whom I later identified as the military chief of Lautaro.. And from then on everything was set in motion.

To not implicate anyone else and avoid leaks that could jeopardize not only the interview, but the lives of the participants, and my own integrity., I decided not to inform anyone at the magazine of the final negotiations, not even my boss, director Libio Pérez..

It must be remembered that at that time The police were under great pressure to obtain results on Lautaro, who accentuated his strategy of the “physical elimination of the enemy”, vulgar murder of people. And, obviously, arresting or eliminating his boss was, without a doubt, a highly coveted jackpot.

A date and place were set to be picked up. There were a couple of attempts that did not work, or that were part of the counter-monitoring work to see if he was being followed or “with tail“, as it was said in the slang. Finally, one night in early September 1991, they instructed me to go to the restaurant. Horse Chickenlocated in Rondizzoni with Viel, south of Santiago, at 8:00 p.m., and to take the necessary measures in advance.

Only my wife knew exactly what I was doing that night, with instructions that if I didn’t show up at a certain time in the morning to contact our director, Libio Pérez, and tell him..

I left the magazine around 5:00 p.m. and stayed until almost 7:30 p.m. driving around in various taxis. When I presumed there was no follow-up I headed to the restaurant. After waiting for about 20 minutes, two guys approached the table and gave me the agreed upon password and asked me to accompany them..

We walked for about 15 minutes along the side of the Panamericana, me looking at the ground, until we turned onto a small, rather dark street. They made me get into the back of a large car and asked me to put on dark glasses, which they brought.

After about an hour of walking around the area (a lot of turning and no long straight paths) We stopped next to a fairly modest house, typical of a town in the southern area of Santiago.. The rear door of the car was in front of the door of the house and they asked me to get out and enter. A few steps later he was inside a room where there was a table, some chairs, cups and sandwiches.

There I waited a few minutes until I heard a noise of greetings and hugs. It was Diego Carvajal (Guillermo Ossandón) who greeted the security team and probably those who provided the house. From that moment I remember one of the security people standing at attention before his boss, but Instead of a military salute, he says something similar to: Hello, how are you? This was Lautaro.

And so began a long interview of more than five hours, which was the first granted by the head of Lautaro to a media outlet. The interview was entirely recorded, and at the end of it I asked him to sign his name and real signature in my notebook., a precaution that would later serve me well. The departure from the place was at dawn and in the same format as the arrival. No problem. They left me on a street near the center of Santiago.

The interview was published a couple of weeks later and featured on the cover of Open Page. That’s where the real problems began..

He Government He accused us of being spokespersons for Lautaro. Channel 7 (TVN) questioned whether the interviewee was Guillermo Ossandón. He Intelligence Department of the Investigative Police (current PDI) invited me to a couple of conversations to ask me about the conditions (place, people, recording, ambient noises, etc.) where the interview had taken place.

Coincidentally, my house was broken into and everything was turned upside down and some very strange things were taken. And the icing on the cake: the Ethics Committee of the College of Journalists opened an investigation against me..

At Página Abierta magazine we had made the decision not to reveal absolutely anything about the interview (neither details nor sources), maintaining professional secrecy at any cost. And so we let the then Investigative Police and the ministries of the Interior and the Secretary General of the Government know. Everyone was warned.

And slowly things became clearer. Ossandón’s signature in my notebook cleared up TVN’s doubts about who the interviewee was. His press chief called me and apologized, to which I responded that I was asking for a public apology for public harm; nothing ever happened.

What happened with the Intelligence people of the Investigative Police was more entertaining: they They knew they were asking me things that I wasn’t going to tell them.ry told them with my best face that I had not recorded the interview, that the pickup was in the northern area of Santiago and that I never saw Ossandón’s face nor did I see a weapon in the place.

They looked at me with a face like… and I looked at them with a face like…, and They suggested to me that I had something to do with Lautaro. And since the five tapes of the interview were in a safe very far from my home, I never knew who or why they broke into my house and whether it was a coincidence or not.. From the summary of the ethics committee of the Colegio Periodistas, I never knew how it ended, and in truth I didn’t care much either.

A few months later we began to receive invitations from groups that worked on security issues and armed groups, some were from the government sector, others from the academic world, and there were also NGOs. Everyone thanked us Open Page having published the interview since it had helped them to get a more real and closer idea of what Lautaro and its people were. There I felt that so much nerve and so much brawling had been of some use.

The curious thing is that less than a year after this exclusive interview I had the opportunity to interview Guillermo Ossandón again. It was in June 1992 in the context of the emergence of a coordinator of subversive groupsheaded by Lautaro, and which had remains of the military MIR and others.

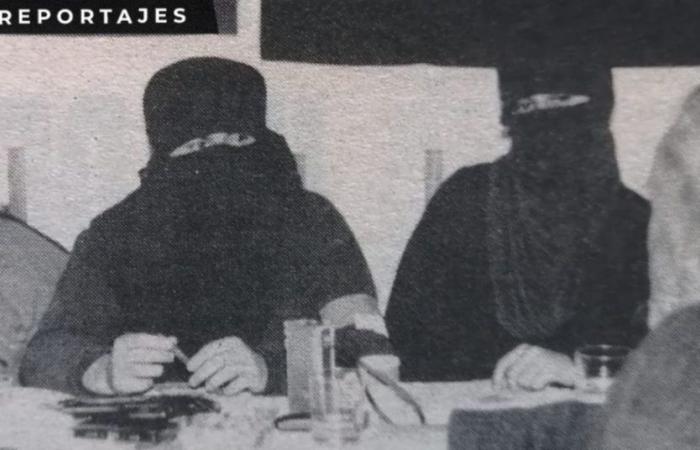

On this occasion there was also a lot of driving, eyes with scotch and at the meeting itself a lot of weapons, including a FAL. It was all very spectacular. They allowed me to take photosall of them hooded and flanked by an armed guard and posters alluding to the subversive coordinator.

After a little while I realized that the subversive coordinator did not have much substance and that it was more of a propaganda operation to try to overshadow several repressive coups that had devastated the Lautaro leadership..

At that point I diverted the conversation and focused on Ossandón, who sat in an armchair, took off his hood and prepared to answer my questions, while I thought that our magazine (Open Page) had managed to interview the Lautaro boss twice exclusively in less than a year. Two exclusives in a row.

But this story almost doesn’t end here. Just two years later, in mid-June 1994, Guillermo Ossandón was arrested in the seaside resort of Cartagena, and I almost, almost, I was next to his hiding place.

At that time we went with my wife and children quite often to the beach of Isla Negra and on our way back to Santiago we had the habit of going to buy cakes at the best pastry shop in Cartagena. That day when we arrived in Santiago and saw the images of his arrest, I discovered that Ossandón’s hiding place was next to the pastry shop..

This time we had decided not to stop by to buy cakes. It was raining. I imagined how much it would have cost me to explain such a coincidence to the investigating police..

Guillermo Ossandón was imprisoned for 10 years until he was pardoned in 2004, and he moved to live in the south of the country. He died of cancer in July 2009, at age 56..

Author: Jaime Gré Zegers, Journalist, at that time Deputy Director of the magazine Open Page.

Credit photos: Jaime Gré Zegers