The 1930s were characterized by the sanction of new official provisions restricting the entry of foreigners. A decree by Agustín Pedro Justo (1932) aimed to stop immigration entry. It established “as an essential requirement that the immigrant have a work contract or agreement.” This posed a challenge for refugees, particularly Jews from central-eastern Europe. Fleeing these anti-Semitic persecutions, many entered our country illegally or from neighboring nations, mainly Paraguay and Uruguay, but also – although less – from Brazil, Chile and Bolivia. Bela Guralnik’s testimony shows the odyssey of thousands of Jews seeking to save themselves from what would be genocide

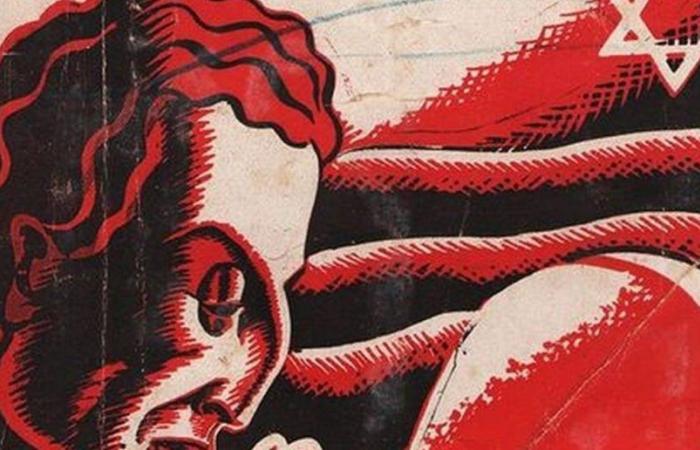

Complete book cover.

In those days of 1935, the young and talented Jewish-Argentine poet Israel Zeitlin, much better known as César Tiempo, had written a devastating attack to demystify the writer and public official Gustavo Adolfo Martínez Zuviría (Hugo Wast), who was the director of the Library National. César Tiempo’s work, opportunely edited by Mundo Israelita, was titled “The anti-Semitic campaign and the director of the national library.”

In this context, one cannot ignore the anti-Semitic impunity of the years of the so-called Infamous Decade (1930-43). It is necessary to point out that the incitement to pogrom and the anti-Semitic preaching that took place during the Uriburism, its development and virulence reached very serious peaks during the governments of Justo himself, Roberto Ortiz and Ramón Castillo.

Just reading the chronology of the Jewish community organizations that combated anti-Semitism in the 1930s clearly illustrates this phenomenon: in 1934, creation of the Popular Organization against Anti-Semitism; in 1935: emergence of the Delegation of Argentine Israelite Associations (DAIA); in 1937: constitution of the Committee Against Racism and Anti-Semitism; in 1941: emergence of the Idisher Cultur Farband / Federation of Jewish Cultural Entities of Argentina (ICUF).

In addition to this process, there were also other political and social organizations outside the Jewish community that confronted Nazism and its discriminatory, racist and xenophobic policies. Anti-fascism was the unifying element and gave a certain programmatic coherence to various groups coming from different currents covering a broad political and cultural spectrum. Some of these were the Association of Intellectuals, Artists, Journalists and Writers (AIAPE, 1935), the Colegio Libre de Estudios Superiores (1930) and Acción Argentina (1940). There were also the publications ¡Alerta! (1941) and ¡Antinazi! (1944).

Likewise, a whole series of anti-fascist organizations must be added, both from the Italian anti-fascist exile and from the Austro-German exile and the Spanish republican exile, such as La Otra Germany (De Andere Deutschland- DAD), the newspaper Volksblatt, Italia Libre, the newspaper L ‘Italia del Popolo, Republican Spain among many. In them, liberals, monarchists, communists, socialists, and anarchists of those origins coexisted, not without strong differences and bitter disputes.

Within these groups described above, various anti-fascist Italian and anti-Nazi German exiles collaborated and contributed to them the experience of those who had directly faced the “Nazi-fascist beast”, while the latter had the possibility of “amplifying” their activities in the exile.

In July 1937, the Committee against Racism and Anti-Semitism of Argentina was founded, which initially held its meetings at the Colegio Libre de Estudios Superiores. As an introduction, the initial declaration referred to the First World War as a breaking point that had shaken the “material and moral structure of the social world” and had also unleashed racial hatred in our country. For this reason, “free men, with very diverse philosophical and political ideas” called themselves together to prevent the oppression and persecution of the Jews, a manifesto that was signed by numerous personalities, including Emilio Troise and Lisandro de la Torre.

This committee managed to attract the support of a good part of the intellectuals, the socialist, communist, progressive and radical democratic political leadership and important sectors of students and the labor movement, even creating an interesting network of branches both in the interior of the country. as abroad, publishing a newspaper called Contra and having the El Coresponsal Argentino press service.

An important organizational antecedent is the Popular Organization against Anti-Semitism -close to the Communist Party-, which was led by a combative member, Dr. Marcos Meeroff. This institution, a pioneer in the fight against racism and especially anti-Semitism, published the magazine Alerta since 1934 and thus sponsored several enlightening books that made history: “Nazism, enemy of institutions”, “American democracies in danger”, “The voice”, “Anti-Semitism, instrument of the enemies of the Fatherland”, “Argentina against barbarism”. Its director even prosecuted the director of the magazine Clarinada for anti-Semitic insults and incitement to pogrom, leading the Argentine justice system to condemn the racist Carlos Silveyra in 1941 (Meeroff: “A battle won against reaction”).

The Ortiz-Castillo presidential ticket for the September 1937 elections promised to resume Argentina’s immigration policy and ensure the situation of the local Jewish community. However, Argentina implemented a severe immigration policy at the time it participated in the Evián Conference (1938) and tightened it in the following months. The topic discussed was German Jewish refugees and Spanish republicans. The United States encouraged the search for a long-term solution, but together with other countries they did not give up on limitations on immigration.

The excuse of the majority was their fear that an increase in refugees would cause greater economic difficulties, although there was a strong anti-Semitic component underlying it. Although the Jews were not explicitly mentioned in these provisions, it is obvious that they referred to them and the Spanish republican exile. President Ortiz defended this discriminatory policy in Congress arguing that: a) Argentine legislation did not recognize the category of “refugee”; b) The fact that, being a forced emigration, they would not be voluntary and permanent immigrants; c) The character of the majority of potential Jewish immigrants was urban, while current legislation gave preference to rural immigrants.

This argument did not prevent the countless obstacles imposed on the Jewish settlers that the Jewish Colonization Association sought to bring into the country: the preference that the law granted to farmers was not sufficiently relevant when it came to Jews. The underlying reason for this negative policy was one: anti-Semitism. In Jewish and democratic circles, this context of rejection created an atmosphere of clear distrust, a mixture of sadness, anger, frustration and horror.

In short, towards the end of the 1930s it was necessary to fight against a widespread Nazi organization in Argentina, which had numerous agents operating from newspapers, magazines and events in closed premises to incite crime. Regarding the strong presence of the Nazis in our country, the massive gathering held by that political structure in Luna Park in Buenos Aires on April 10, 1938 was more than significant, a story that we will address in our next installment.

“Bela for some, Belita for many.” Nosotros Magazine, printed edition in El Litoral, Saturday, September 15, 2015. Bela Guralnik, now deceased, had to flee Germany with her parents when she was very young, due to the rise of Nazism. She was a member of the Argentine Israelite Cultural and Sports Association IL Peretz of Santa Fe and treasurer of the Freilej Choir of the institution.

#Argentina