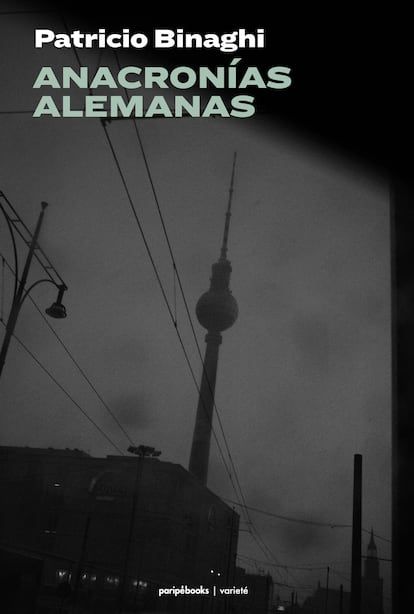

In one of the last chapters of German anachronies (Paripé Books, 2024), Patricio Binaghi (Buenos Aires, 48 years old) recounts the exact moment in which he chooses the image that will go on the deck of his future book. It is a photograph of Peter Lindbergh that shows, in a cloudy black and white, one of Berlin’s communication towers. It is a metaliterary wink, but also demonstrates to what extent life and writing shake hands in the first book as author of this producer, cultural manager, collector, researcher and Argentine editor based in Madrid. “The last chronicle was written in real time, and I liked that this detail was sneaking,” he says. “As an editor, I spend the day reading texts that come to me and I see very crowded things. I wanted to give my freedom as a writer.”

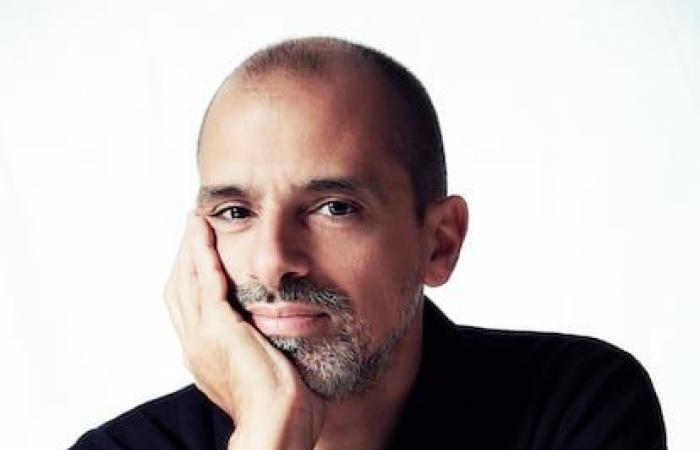

Patricio Binaghi grew up in Buenos Aires and studied at the German school in the Argentine capital. That was the first contact with a language and a culture that did not find its own, but in which he lived immersed until 18 years. “The majority of my colleagues were from German families, second or third generation. Only a few belonged to another ancestry,” he recalls. Over the years, he returned to live in the Germanic country, first in Berlin and then in Düsseldorf, in stays that alternated with times in Madrid and Buenos Aires. Later a doctorate in Leuven (Belgium) dedicated to German photography in the twenties began. Again Germany, again that culture that was part of it despite the distance. “I don’t finish elucidating where that attachment to Germany comes,” he reflects. “It is a country that is close to everything I study, and also alien, because I have nothing to do with it. That is mixed with the migrant status that I have here in Madrid, and with which I had those years in Düsseldorf, that strange feeling of being a Latin American in Europe.”

The turning point took place in January 2024. His niece, which he studied at the same Buenos Aires school that he had attended, traveled to Germany for a school exchange and Binaghi made with her the journey from Madrid to Berlin. “On the flight back to Madrid, three and a half hours, I started writing a story of the whole trip. When I returned I taught Andrés Gallina, an external editor with whom I collaborate.” Gallina’s response was enthusiastic and Binaghi began reviewing notes taken during her trips to Germany after the pandemic, to do doctoral research stays. From there arose his book, which brings together chronicles dated between 2021 and 2024 in cities such as Marbach, Hamburg, Berlin, Colonia or Dusseldorf.

German anachronies It is, first, the diary of a bibliophile and a researcher. Throughout his professional career, Binaghi has worked for the Argentine Ministry of Culture and has collaborated closely with photographer and designer Juan Gatti. Currently, he writes his thesis, carries out artistic and editorial projects, collects books, posters, magazines and brochures. Also directs an independent magazine, Bibliotechwhich tracks files, libraries and collections worldwide to unravel the keys to this fascination. With Paripé Books, its own publishing house with headquarters in Spain and Argentina, has published works by current authors such as María Gainza, Guillermo Alonso or Camila Fabbri, in addition to books by artists such as Pepo Pérez and jewelry bibliophiles such as an ambitious volume on the library of Jorge Luis Borges. Of all this there are traces in these pages that draw a polyhedral and contradictory look on Germany. Binaghi is fascinated by his architecture of the twentieth century, the contrasts forged in the Cold War or the presence, never completely buried, of homoerotism. “It is a very extreme country in regard to affections and sex,” he explains.

-

It does not seem a coincidence that Binaghi confesses his admiration for the photograph of the new objectivity of the twenties. Karl Blossfeldt’s botanical catalogs and August Sander’s portraits remain influential. “The typologies are something very German,” says Binaghi, who confesses Proust, Sebald and other teachers of the description. “In the thorough they shoot for the reader certain objectives of the narrator.” Several photographer names of the Düsseldorf school such as Bernd and Hilla Becher also parade for their pages, which for half a century toured Germany to portray industrial structures – cooling torres, water deposits – scattered by the landscape. If the photographic series of the Becher, apparently impassive, ended up transparent the identity of a country, also the thorough descriptions of Binaghi – what he asks in the restaurants, the books that he leaflets, the songs he listens to, the means of transport that he takes – contain cracks through which the intimacy ends up filtering: the duel for the loss of the parents, the problems of the parents Migrant’s estrangement.

In the same way, politics bursts into the description of a society that encapsulates many of the current tensions. Binaghi witnesses the rise of ultra -right in Germany or the destruction of the Argentine cultural fabric after Milei’s victory. “Germany always seems to be in a very fragile balance. The German society seems contained, but a spark is enough for everything to explode. Madrid is a city where I am never afraid. But, in Germany, already because of having brown skin I automatically remain outside the system. denazification He put a veil, but he did not go to the problem. When I go to an antique market and so much appears memorabilia On the time of the third Reich, the first thing I think is that this was at someone’s house. Why, eighty years later, this is still at someone’s house? ”

In German anachronies, Binaghi Husmea in historical archives, Lee Manuscripts of Stefan Zweig and finds an autograph by Hermann Hesse in a apparently worthless book. He cites Joseph Roth and Robert Walser, Leni Riefenstahl and Grete Stern. Beyond the shadows, yours is a love letter to the roots of a certain cosmopolitan, multilingual and humanistic European culture. It does not surprise that two of its current projects – the Bibliophile Magazine Bibliotech and the store online of old laminarium posters and publications – claim the intimate and political weight of the printed paper. “Paper is an organic material, the human being and paper are destined to be and understand, and the introspection and silence of the library and the archive are perfect places for that encounter,” he says.

Therefore, the debut as a writer of Binaghi is an invitation to rediscover a country and a culture that is not exempt from nostalgia. “I think nostalgia is in Argentine DNA,” he jokes. “I live in today’s world, I use today’s technology, but I see today’s things that I don’t like and things from the past that I miss without having lived them. I know it is something totally utopian. But in that disruption of permanent time is where my life takes place.”