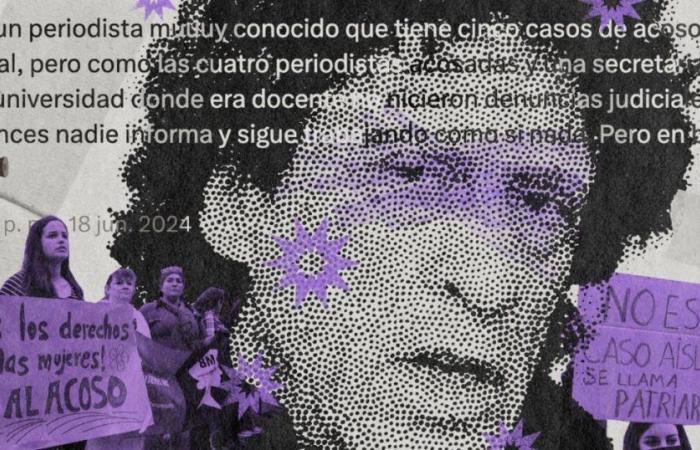

A series of tweets on of international C5N on the Gato Silvestre program and on Eduardo Aliverti’s radio. A reference within Latin American progressive journalism. The testimonies were forceful and of unusual impunity: they say that the guy masturbated in front of colleagues. The length of the stories also shows that there were silent accomplices: how did a harasser sustain himself between 1994 and 2019? Because he could. The structures of male domination guaranteed impunity. And traditional journalism is one of the best students when it comes to structures of male domination.

From the digital conversation it jumped to the portals and became news. Nobody was surprised. According to the global study on sexual harassment in newsrooms published by the World Association of Newspapers (WAN-IFRA) in 2022, 41% of female journalists have suffered verbal and/or physical harassment in the workplace. Only 1 in 5 have reported it. Which means that 80% of cases remain unreported.

At least I had not heard, known or read the testimony of a direct victim of this journalist who is a harasser on duty. It is true that there were rumors and suspicions (“He is a jerk.” “He is lecherous.” “He is a lecher”) but based on rumors and suspicions you cannot denounce anyone. Without the consent of the victims, either. No complaint is made alone.

Feminist journalism is not based on rumors and suspicions. It is based on people’s desire, on what they want, search for, decide what can repair them, heal them and restore peace to them. There is a method: we investigate, we document, we establish patterns, we decide together how, where and at what time. We know that what we say has a punitive response, that is why we communicate responsibly: harassment is not the same as sexual abuse, much less than rape. We are very aware that each word responds to a criminal type and a particular level of severity. Not all victims see justice as a synonym for jail. Some want to be kicked out of their workplaces, others simply want to stop bothering them.

We know that victims speak when they can. In general, they are the ones who come to us and the path is collectively built between journalists, human rights organizations, feminist organizations and lawyers. We try to protect them and surround them with nets. Reporting workplace harassment has its costs for them and their environments. Who wants to put themselves in the center and expose their privacy from a subjectivity like that of victim? It is in no one’s interest to report.

Even today it means facing stereotypes, disbelief and the suspicion that “he must have done something”. Even today there are people who doubt our word. Even today it is exposing oneself to a public debate about one’s own life: from one’s physical appearance to the clothes we wear or our past ties.

Even today there is the risk of being marked in several ways: out of curiosity or morbidity, for a while no one will talk to you about anything other than the complaint; Due to prejudice, it is likely that you will be seen as “the problematic one” or “the complicated one” and they will not call you to work. That is why not all women, lesbians, transvestites and trans people who have gone through harassment situations choose to speak out, and it is okay for that to be the case. They feel guilt, fear and shame because we are also plagued by gender prejudices and stereotypes. Each one processes it as she can.

“It is like this here”

The first job interview I had for a job in the media was at a cable TV station in the neighborhood where I grew up. “Are you going to put up with people touching your ass, producers supporting you, or saying things to you on the editing floor?” the executive producer who was interviewing me asked me. I was stunned.

That morning he had read all the newspapers and had studied the names of Ministers and government officials. She was prepared to answer any question about the political and social situation of the country, but not for what I was asking. “It’s like that here,” she told me before my silence. I didn’t stay for that job.

A few months later I had another interview to produce a radio program. The driver summoned me and other applicants to his apartment. At that time I didn’t wear my glasses all the time. He asked me to wear them because he had seen the photo on the CV he had sent and “they looked sexier on me.” He proposed to us production candidates that we do a role-playing dynamic in which we had to convince an interviewee to give the grade to him, putting seduction into play as a tool. I did not do it. I didn’t stay in that job either.

Little by little, insisting with summaries, I began to write in a Buenos Aires magazine. They were my first collaborations in the City of Buenos Aires. I still lived in La Matanza. I had an editor from whom I learned a lot. One afternoon I had to bring an invoice to collect the notes I had published. I was excited because I was going to see a real newsroom. Other media outlets operated in the magazine building and I had to share an elevator with an international journalist whom I read, listened to, watched and admired a lot because he covered Latin America, everything I had always wanted to do. We only shared a double decker ride, but it was uncomfortable. I remember that he scanned me with his eyes and that I wanted to get to my destination quickly. The true feminine intuition that is activated as a survival instinct.

More than 15 years passed since these uncomfortable and inappropriate situations, which served as a warning to me at a time when little was said about harassment and abuse of power in the workplace in journalism, or in any other profession. I knew that in order to work in the media, you had to develop a skill: live with discomfort and arm yourself with shields, as we all do in any other structure of male domination. Sexism was naturalized and silenced. No one spoke of these terms and conditions as a problem, but rather as a condition, a gateway. “This is how it is here,” I had been warned and welcomed.

So, when I felt that the guys were scanning me with their eyes, I went and faced them with confidence, I told them my name and what I was doing while I thought to myself “you’re not going to make me uncomfortable, you piece of shit.”

Perhaps because I was stubborn and because my way of confronting male domination is always provocation: I never stopped wearing tight dresses, short skirts or rubberized pants. On the contrary, I used them as a shield, like a disguise that threw them off when they faced me and I stood up.

All situations always bordered on a thin line. A boss or colleague has never touched any part of my body without my consent, nor showed me his member. But they made me feel uncomfortable countless times: that atmosphere in which we were (are) forced to work does not have to be like that.

We journalists rarely talked about these situations, but we noticed them and we took care of ourselves. One day in a radio studio, a colleague saw a male colleague looking at me lustfully and as he sat next to me, she suggested we exchange places without saying anything. My shield was other things. In our own way we told each other: “We are not alone.” But my favorite shield, the most effective, was to invoke my partner, who was also a journalist. Respect for another man, and even more so if he is a colleague, can be a super shield. There is nothing more corporate than machismo. Machista journalists are corporate squared.

It is true that as I worked more and more in the media, and especially focusing on the agenda of human rights and gender-based violence, the uncomfortable situations became fewer and fewer. Sexual harassment in the workplace is, first and foremost, an abuse of power.

In these years I hugged colleagues who had to leave radio studios crying, I advised male colleagues who did not know what to do when they discovered that they ended up involved in a night of drinking with an abuser, I heard countless harassment situations that were not made public but that ended in resignations and displacements of places. Most of them were their displacement because the guys don’t leave anywhere alone.

Sexual harassment and abuse of power are an obstacle to the development of our professional growth and are leaving us out. They climb the ladder, climb the space of power, prestige and money. We continue in the most precarious places and some leave the profession.

Visibility also protects me today, a little. Ni Una Menos was a milestone in Argentina. Many of us who founded that movement unexpectedly occupied places in the public debate. In any case, do not believe that feminists with a public voice are not harassed. The guys have sophisticated their ways and find perverse ways.

On Sunday, when the name of the harasser was revealed, many of us thought at that moment about how other colleagues who were reliving situations they had gone through with that person felt when reading the stories that the Clarín journalist shared. We know that this is just beginning. “Colleagues: we are here for whatever you need. Hugs and strength,” published the Argentine Journalists collective.

The feminism proposal came to tell us all that the terms and conditions in life – and in journalism – can be different. I say it without shame: it was us feminists who built the conditions of possibility so that all those uncomfortable and inappropriate situations could be told from a legitimate voice when the victims can, want or so desire. It was us feminists who came to say in the media and in life: “Here it can be another way.”