Local miners confront Chinese mining company

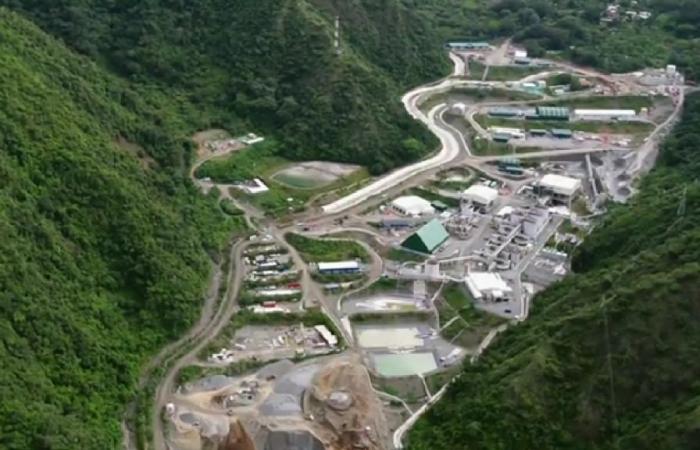

Screenshot from YouTube video Buriticá Mine: Colombia’s modern mining for the world. By Zijin-Continental Gold. Fair use.

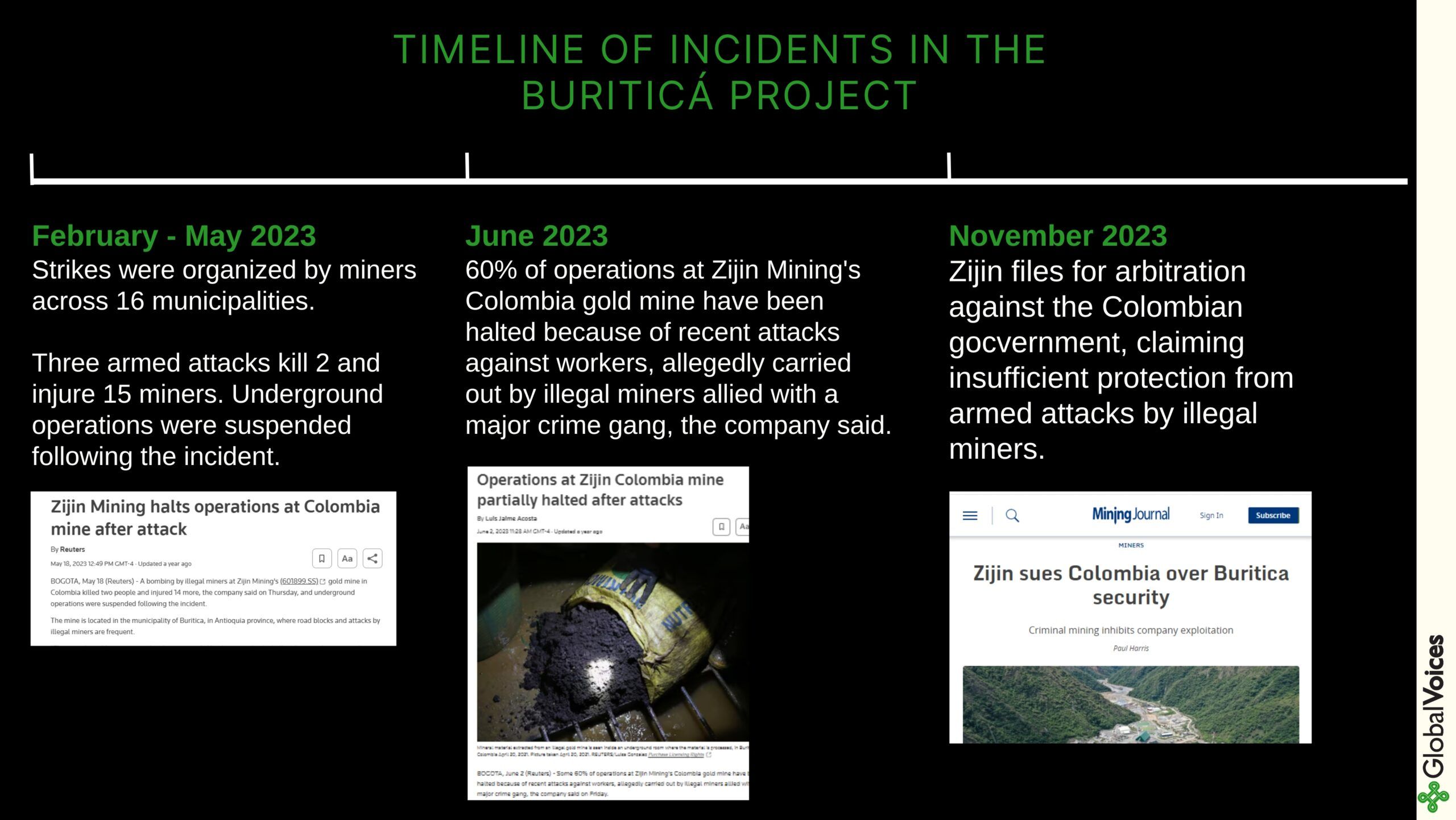

On May 30, 2024, four communities in Buriticá, home to 10,000 people in southern Colombia, sent a letter of support demanding that the authorities take urgent action against the growing violence near the country’s largest gold mine. This mine is owned by Zijin Continental Gold, a subsidiary of Zijin Mining, known for its lawsuit against the Colombian government in November 2023 for failing to protect the mine from attacks by local miners.

Local miners do traditional small-scale mining in the region. They are called “ancestral” miners because they have inhabited these lands and have dedicated themselves to mining many centuries before national and international corporations arrived. However, in Zijin’s eyes, these are illegal or informal miners. The Colombian Government considers these claims a fair request from the community, and at the same time a threat to Zijin’s operations.

The environmental, social, economic and legal tensions in Buriticá reflect the complex relationship between large-scale mining activity and local miners. In addition to the environmental impact, which includes deforestation and water exploitation, Zijin faces growing social discontent, which is quickly becoming the face of climate justice issues in Colombia.

Recently, local miners blocked the entrance to the mine, preventing locals from accessing food, health services and education for children, according to a letter from the community.

In the midst of the serious situation that we are facing in the municipality (…), we turn to you as entities representing the government, so that URGENT attention is given to the crisis and violation of rights that we are experiencing (…)

The regional body of ancestral miners signed a petition asking Zijin to guarantee the 140 hectares they have been claiming for almost ten years. Traditional mining is vital for the income of nearly 300 families and hundreds of informal miners.

These miners often work under risky conditions in tunnels near Buriticá that are owned by Zijin, so it is urgent that the company formalizes its activities and stops classifying them as “illegal miners.” They seek to assert their rights to work safely in the mine.

see more

In 2020, after acquiring the largest gold deposit in Colombia, Zijin got engaged to mitigate the negative impact of its mining activities, and promote the rights and well-being of the communities of Buriticá.

However, frequent blockades and armed attacks carried out by informal miners or criminal groups have paralyzed the company’s activities. These attacks lead to economic losses and have a secondary environmental impact, since traditional mining involves activity in sensitive areas, which contributes to deforestation and ecosystem degradation.

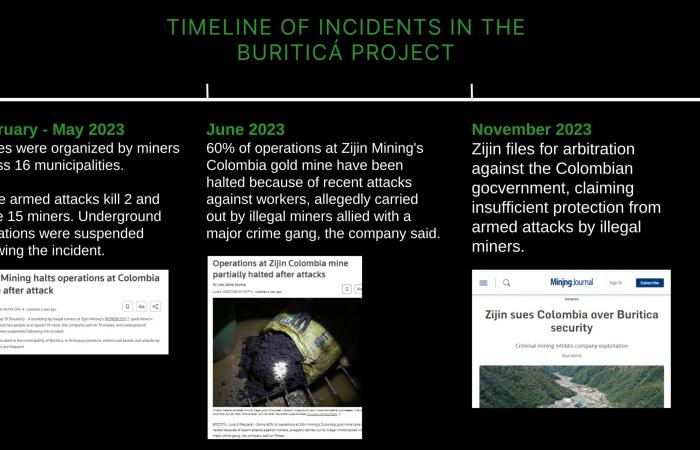

In November 2023, Zijin filed a lawsuit and indicated that it may consider withdrawing its activities if conflicts continue, as it anticipates that local communities may exacerbate the situation. The case is under review in Colombia’s Constitutional Court and could put 4,200 jobs and $95.4 million in taxes and royalties at risk.

This movement occurred during President Gustavo Petro’s visit to Beijing, in which he met with Chinese President Xi Jinping, who welcomed the Latin American country to his “Chinese Belt and Road Initiative” global infrastructure project and committed to promoting sustainable development together.

The history of violence in Butiricá

The Zijin mining company, whose largest investor is the Chinese Government, extracts minerals such as copper, gold and lithium, among others. It was founded in 1986 in Longyan, China, and now has 17 mining projects distributed in Colombia and 15 other countries around the world, including lithium mines in Argentina and copper mines in Peru. The Butiricá mine is the largest gold mine that Zijin has acquired in Latin America.

“Our vision is to become the most modern gold mine and the first in Colombia to be environmentally responsible,” said James Wang, general director of Zijin Continental Gold’s Colombia offices, in its sustainability report. Among the company’s objectives are the preservation of biodiversity, the responsible use of water and contributing to the well-being of the community.

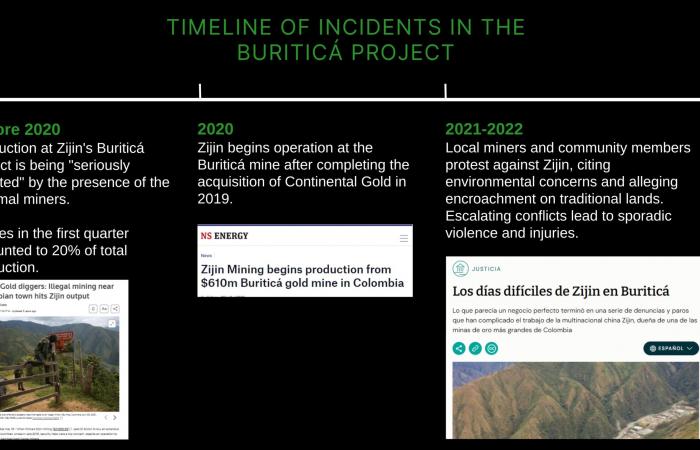

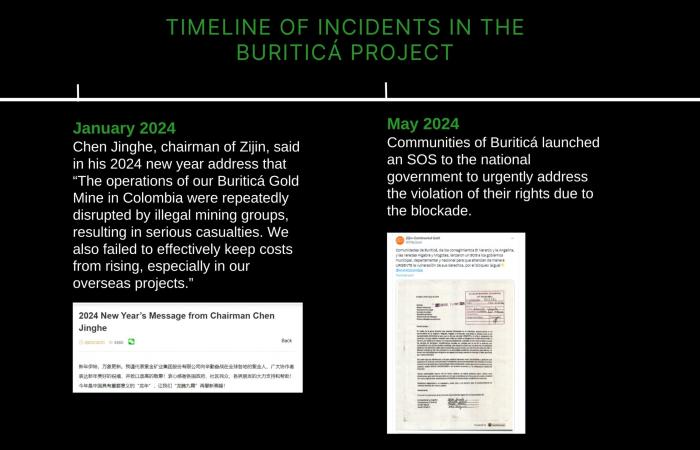

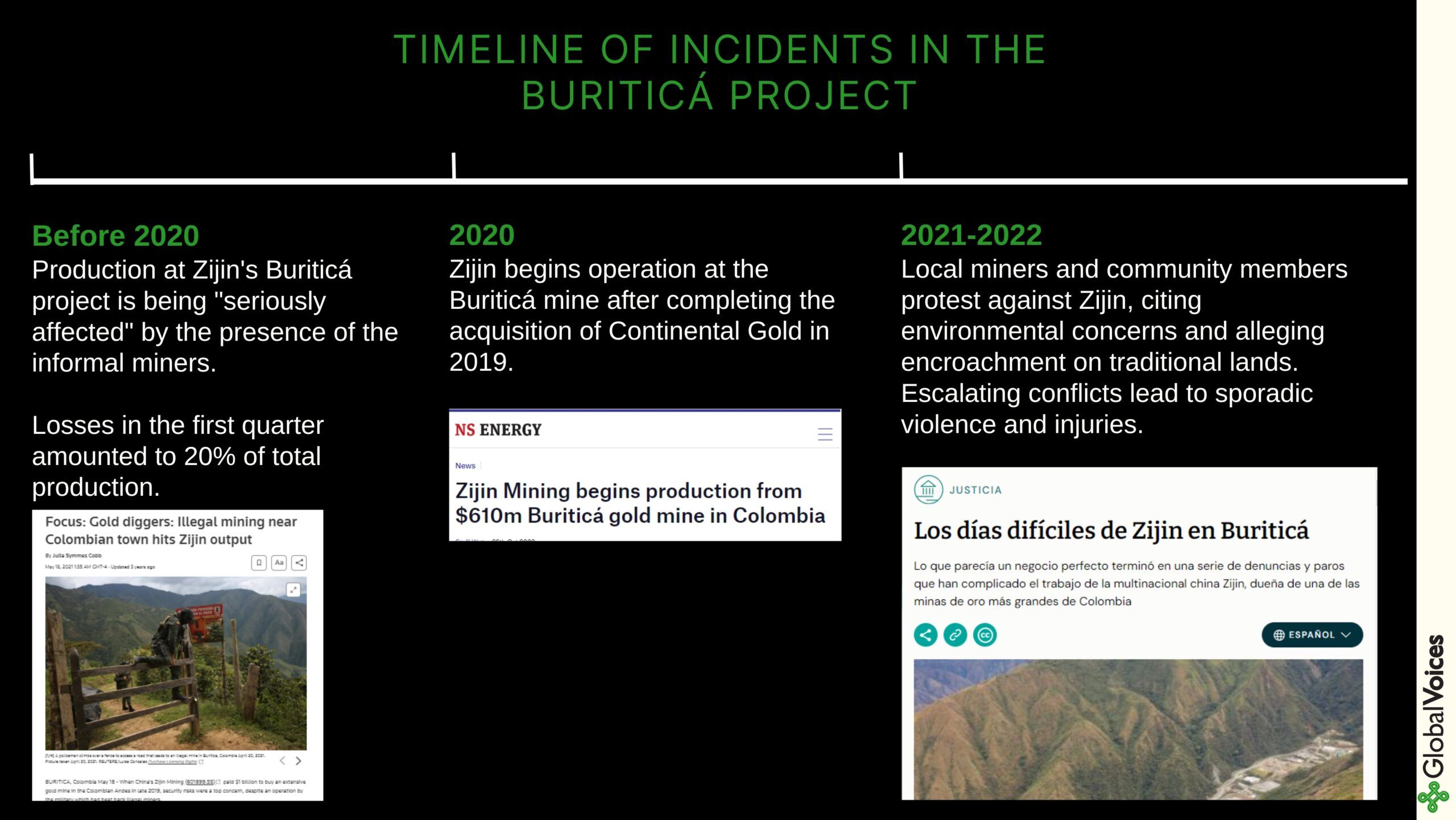

Global Voices Timeline

The conflict in Buriticá is not new, and deepened after Canadian Continental Gold acquired Zijin Mining in 2019. This mine has an estimated daily production of 4,000 tons of gold, and has a history of violence behind it, which includes the death of workers. caused by informal miners, it is argued. However, the growing frustration of the ancestral miners and the presence of the Clan del Golfo group, which uses the tunnels to carry out its activities, have intensified the conflict.

Global Voices Timeline.

A year later, Wang told Reuters: “It is really very complicated to manage these areas.” Thousands of informal miners have worked in hazardous conditions in hundreds of tunnels and nearly 150 clandestine processing sites inside Biriticá, the outlet reported.

Zijin claims to actively engage with miners and local communities through projects that aim to formalize informal mining work and promote social development. However, ongoing blockades and armed attacks complicate the company’s operations and also threaten the security and stability of local communities.

Wang said the government needs to “provide more assistance and implement laws and regulations in the region.” In 2024, the company admitted that it had failed to control the costs involved in creating projects such as the Buriticá mine.

Global Voices Timeline

Ancestral miners from Buriticá denounce discrimination

Although gold mining sounds controversial in the context of modern, large-scale global exploitation, in some communities, this activity is deeply connected to a community’s culture, lifestyle and income. Mining activity in Buriticá long predates Spanish colonization, which began in 1541. Today, at least 350,000 Colombians derive their income directly from gold mining, according to the Harvard Review of Latin America.

In 2020, Patricia Gamba explained in a report by the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) that gold mining in Buriticá is an ancestral practice. She writes:

The main sociocultural characteristic of Buriticá and its neighboring municipalities is that mining (…) especially those related to gold production is an ancestral practice. For this reason, there are groups with a common history around gold production and with shared experiences. These groups interact with each other and have collective behaviors, as they live within very similar political and economic realities.

The main sociocultural characteristic of Buriticá and its neighboring municipalities is that mining, (…) especially the activity related to the production of gold, is an ancestral practice. This is why there are groups with shared stories and experiences about gold production. These groups communicate with each other and act collectively because they live under the same economic and political reality.

Although Colombia has delivered nearly 7,000 mining exploration titles since 2022, workers continue to claim that the Government of Colombia failed to comply with an agreement from September of that year as it continued to attack small-scale mining activity and persecute protest leaders. which violates the reforms of the country’s Mining Code.

In February 2023, authorities in Buriticá ordered the destruction of illegal mining infrastructure, leading to an indefinite mining strike in 16 municipalities. Negotiations between miners and the government have since begun and continue amid protests and blockades.

Violence is on the rise and gold mining in Colombia is challenging local communities as age-old practices, international conglomerates and global demand for the metal create conflicting interests and obligations. Authorities must decide which side they are on between these competing interests and how to balance the protection of the land, communities and the interests of international companies.

Global Voices contacted Zijin via email for comment on the legal proceedings. The company did not respond to our requests.