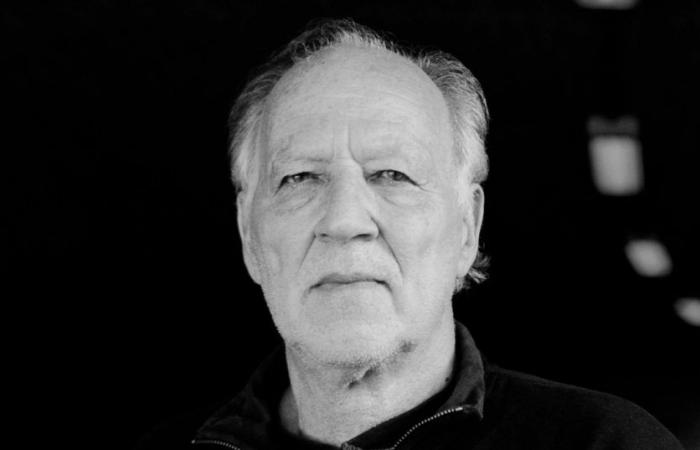

The great German filmmaker tells his life story.

THE SELF-TAUGHT WISE MAN

In a final passage of Each one on their own and God against everyone, Werner Herzog refers to the fact of having participated in a film by Edgard Reitz. Herzog has directed many films, but he has also participated as an actor in titles as diverse as Mr. Lonely (Harmonine Korine), The power of a God (Peter Fleischmann) or Jack Reacher(Stepehen McQuarie), among others. Not long ago, she played Alexander von Humboldt in Heimat, the other land. That he conditioned Reitz to appear on the scene with him is a cordial anecdote of the many that are read with amazement in the book, but what is important is the discreet pride of having been the German polymath, naturalist, geographer and explorer in fiction. . Herzog’s curiosity is voracious. He is interested in philosophy, languages, theology, distant civilizations, the cosmos, neurosciences, and mathematics. In chapter 30, titled “Villains,” Herzog summarizes his path: “I have always been a convinced autodidact, who has never believed in universities.”

Each one on their own and God against everyone It has a prologue, 36 chapters, the complete list of his films until 2022, another list of his operas and some final pages of acknowledgments signed in July 2021. The first chapter refers to an experience of astonishment that would result in a modification of the consciousness of a 16-year-old boy during a night at sea. The laborious description of that decisive moment, the precision of the vocabulary to refer to a maritime profession and the attention paid to heterogeneous details define the filmmaker’s prose. He may be remembering a passage from the filming Aguirre, the wrath of God, an exchange about some mathematical questions with Roger Penrose or some anecdote from his grandmother; the manifest rigor is even. Details do not escape Herzog.

In his book of memoirs, Herzog dispenses with the calendar, the straight line, the biographical periods associated with institutions and those events that define a trajectory. There are childhood memories, passages dedicated to parents, siblings, grandparents, different wives. Some paragraphs cited from his great-great-grandmother’s diary date from 1829, but the organization of the book responds to an associative montage of intense segments and instances of learning. The declared amazement of the beginning and the intrinsic relationship with curiosity are constitutive of a temperament forged by the lack and contingencies of an era.

Herzog was born in September 1942, in Munich, the city that most fervently embraced Adolf Hitler’s delusions; It was the “capital” of the Nazi movement, and became rubble in 1945. Herzog’s mother decided to leave that city and move to a rural area, Sachrang. In a passage from chapter three, on page 31, you can read: “My brother Till and I grew up surrounded by misery, but we were never aware that we were poor, except perhaps for the first two or three years after the war. We were always hungry and my mother couldn’t bring enough food. We ate dandelion leaf salads, and my mother made plantain syrup and fresh spruce shoots.” Allusions to that period are never included as an oblique plea for commiseration. They are simply the material conditions with which Herzog initially felt the world. On the page after the quote, a domestic conversation is added. The brothers cry from hunger, the mother responds to her complaint by telling them: “Boys, if I could cut a piece of meat from my ribs, I would, but I can’t.” Herzog concludes: “At that moment we learned not to complain again. I find the culture of whining abhorrent.”

From this last anecdote we can predict that peculiar characteristic of the filmmaker’s personality, capable of resisting the inclement weather in Antarctica or the scorching heat next to a volcano, or filming in the jungle without any comfort or walking for weeks from the hometown to Paris to visit Lotte H. Eisner and thus “stop” the cancer of film criticism, which always defended Herzog’s films. Tenacity and willpower surely come from those initial impressions of a world marked by lack. This is indirectly recognized by Herzog, who did not need psychoanalysis to investigate the marks of childhood on his psyche. He disdains Freud’s invention and the leading role of dreams, perhaps because he does not believe that all people dream at night. From what has been said so far, Each one on their own and God against everyone It seems like an autobiography, but if it is, as happens with Herzog’s films, he invests it with his stamp. That is, he disobeys rules and expectations and imposes his idiosyncrasies. In other words, the book gathers signs of life: the intensity of a trip or a filming, an instance of learning or a meeting with a friend. Chapter 23, dedicated to the English writer Bruce Chatwin, is moving. There Herzog’s loyalty to his friends can be verified. They are glorious paragraphs.

Herzog was never interested in cinephilia. His distrust of the refinements of bourgeois culture is evident page after page. Nothing could be further from the director of Fitzcarraldo than the dilettante relationship with knowledge and culture. In this sense, Herzog dissociates cinema from art and playfully places it in relation to knowledge. His films are adventures of knowledge, expeditions that are fueled by a need to know and satisfy curiosity. He abhors academicism, but knows how to venerate what can only come from the training of universities. Indeed, Herzog can praise Walk of Thomas Bernhard and at the same time prefer Pelayo’s position on free will and its consequences regarding sin over the Augustinian perspective on its intrinsic nature; can also state that the Oxford English Dictionary –the twenty enormous volumes– is “one of the greatest cultural achievements of humanity.”

From this declaration of love for a book that he considers the book of books, a magnificent anecdote with Oliver Sacks emerges, a substantial example of how Herzog ties together a story of everyday life with a certain epic of knowledge. This is how he usually refers to his films. This person or that situation is brought back and used in this or that film of his. Without saying it, a method and a conception are revealed: his cinema comes from a collection of experiences and knowledge, and also from a speculative passion that comes from a marriage of observation with imagination. Chapter 32, “The Reading of Thoughts,” is remarkable, no less than the brief but cinematically substantial “The Truth of the Ocean,” where Herzog discusses with the tradition of the cinema vérité and rehearses a notion of truth outside the documentary/fiction distinction that he calls “ecstatic truth.”

The chapters entirely dedicated to cinema are few, beyond the fact that the relationship with his films is a constant. The book includes fragments (some unpublished) of some of his diaries during filming; those of The Ballad of the Little Soldier are as exhaustive as they are ominous, the fact is that witnessing how children naturalize the act of annihilation could not fail to be. About such extreme experiences there are no theorizations about shot scales, camera movements or any discussion about a lens. Nor explicit references to cinematographic discourse, as could be read in texts by other colossi of the 20th century, such as John Ford or Jean-Luc Godard. In chapter 14, “Doctor Fu Manchu,” the extensive first paragraph slips a poetics, or perhaps the spirit behind a poetics, or something like an ontological sensation that determines a formal search throughout his films: “In My innermost being was firmly convinced that I would not reach the age of eighteen. Then, when I reached that age, it seemed impossible to me that I could live beyond twenty-five. Consequently, I began making films assuming that they would be the last ones I would direct. “Why not have the courage to find ways that had not existed until then?”

There is no shortage of famous stories that, we already know, will come from Herzog’s mouth, a collection of delirious exploits that pass from mouth to mouth or are rewritten in newspaper or magazine articles. Herzog returns to the shoe he ate for losing a bet with filmmaker Errol Morris; also the occasion in which he stabbed one of his brothers or the thousand battles with Klaus Kinski, who is always described as a man from another world. He chooses to leave a first-order concern for the last chapter. He asks himself: “What will a world be like without a deep visual language, that is, without my profession?” He is a question thrown into the present and the future.

Herzog, Werner, Each one on their own and God against everyone. MemoriesBlackie Books SLU, Barcelona-Buenos Aires, 2024, 346p.

*Published in Revista Ñ in June.

Copyleft 2024 / Roger Koza