We are in full moon fever. A growing number of countries and private companies have the Earth satellite in their sights in a race for resources and dominance of space. But are we ready for this new era of its exploration?

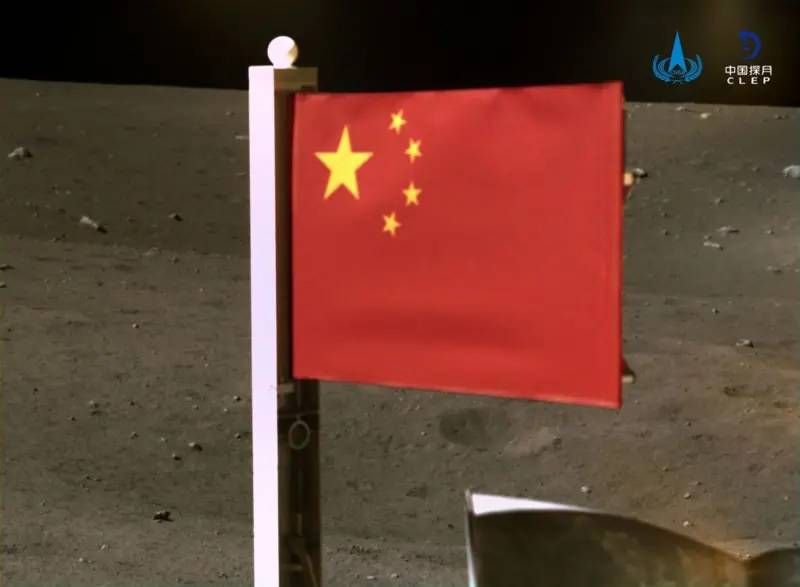

images of the flag China deployed on the Moon generated headlines this month. It is the fourth moon landing for the Asian country and the first mission that has brought samples of its hidden side back to Earth.

In the last 12 months, India and Japan They have also landed spacecraft on the lunar surface. In February, US company Intuitive Machines became the first private company to put a lander on the Moon. And there are many more missions that are underway.

For its part, the POT wants to send humans to the Moon again. Its Artemis mission astronauts plan to land on the moon in 2026. China says it will send humans in 2030. And instead of fleeting visits, its plan is to build permanent bases.

But at a time of renewed push by great powers, this new space race – after the one that began in the 1960s – could cause tensions on Earth to reach the lunar surface.

“Our relationship with the Moon is going to change radically very soon,” warns Justin Holcomb, a geologist at the University of Kansas (USA).

The speed of space exploration is “exceeding our laws,” he says.

Does the Moon have an owner?

A 1967 UN agreement states that no country can claim ownership of the Moon. Instead, the Outer Space Treaty It says that it belongs to all of us and that any exploration must be carried out for the benefit of all humanity and in the interests of all nations.

Although it sounds very peaceful and collaborative – which it is – the driving force of the Outer Space Treaty was not cooperation, but Cold War politics.

As tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union rose after World War II, there were fears that space would become a military battlefield, so the key part of the treaty was that nuclear weapons could not be sent into space. space. More than 100 nations signed it.

A new and important factor is that modern lunar missions are not just the projects of nations, but private companies also compete.

In January, a US trade mission called Pilgrim announced that it would take human ashes, DNA samples to the Moon and a branded sports drink. A fuel leak prevented its arrival, but sparked debate about how to fit the shipment of this eclectic inventory with the principle that exploration should benefit all of humanity.

“We are starting to send things there just because we can. There is no longer any kind of logic or reason,” says Michelle Hanlon, a space lawyer and founder of For All Moonkind, an organization that tries to protect the Apollo landing sites. “Our Moon is within our reach and now we are beginning to abuse it,” she warns.

The precious lunar resources

But even though private travel is on the rise, country governments remain ultimately the key players in all of this. Sa’id Mosteshar, director of the Institute of Space Policy and Law in London, says that any company needs the authorization of a State to go to space, which will be limited by international treaties.

Entering the select club of travelers to the Moon continues to have a lot of prestige. After the success of their missions, India and Japan can boast of being global space players.

And a nation with a thriving space industry can provide a big boost to the economy through jobs and innovation.

But the race for the Moon offers an even bigger prize: its natural resources.

Although it appears quite arid, the lunar terrain contains minerals, such as rare earths, iron, titanium and heliumwhich is used in all types of products, from superconductors to medical equipment.

Estimates of the value of all this vary greatly, from billions to trillions of dollars. . So it’s easy to understand why some see the Moon as a place to make a lot of money. However, it is also important to keep in mind that this would be a very long-term investment, and that the technology necessary to extract and return these lunar resources is still a long way off.

In 1979, an international treaty declared that no state or organization could claim ownership of lunar resources. But it was not very popular: only 17 countries signed it and among them was none that had been to the Moon.

In fact, the US passed a law in 2015 that allows its citizens and industries to extract, use and sell any space material.

“This caused tremendous consternation among the international community,” says Michelle Hanlon. “But little by little, others followed suit with similar national laws,” including Luxembourg, the United Arab Emirates, Japan and India.

The resource with the greatest potential

Something that could be the most in-demand resource on the Moon is a surprising one: Water.

“When the first lunar rocks brought back by the Apollo astronauts were analyzed, they were thought to be completely dry,” explains Sara Russell, professor of planetary sciences at the Natural History Museum in London (United Kingdom).

“But then there was a kind of revolution about 10 years ago and we discovered that they have little traces of water trapped in phosphate crystals.”

And at the poles of the Moon, he says, there are even more: the ice reserves of water are frozen inside craters.

Future visitors could use the water for consumption, to generate oxygen and even to make rocket fuel, splitting it into hydrogen and oxygen, allowing them to travel from the Moon to Mars and beyond.

The Artemis Accords

The United States is now trying to establish a new set of guiding principles around lunar exploration – and exploitation.

The Artemis Agreements They state that resource extraction and use on the Moon must be done in a way that complies with the Outer Space Treaty, although they say some new rules may be necessary.

More of 40 countries have signed until now these non-binding agreements, but China is one of the most notable absences. For some, the new rules for lunar exploration should not be led by a single nation, in this case the US.

“This should be done through the United Nations because it affects all countries,” says Sa’id Mosteshar.

But access to resources could also provoke another confrontation.

Although there is plenty of space on the Moon, areas near ice-filled craters are prime lunar targets. What will happen if everyone wants the same place to set up a base? And once one country has established one, what is to stop another from establishing another too close?

“I think there is an interesting analogy with Antarctica,” says Jill Stuart, a space law and policy researcher at the London School of Economics in the United Kingdom.

“We will probably see research bases being installed on the Moon as is done on that continent.” (YO)

This article was written and edited by our journalists with the help of an artificial intelligence translation tool, as part of a pilot program.