I have several friends who are bothered by the celebrations of “round numbers”: the commemorations that are made, with varying degrees of intelligence or triviality, when two hundred years have passed since the birth of Baudelaire, for example, or one hundred since the death of Proust, or four hundred of the publication of Quixote. I understand them, because these anniversaries tend to be light and opportunistic and rather frivolous, but I confess that I fall into them: I have sometimes made the mistake of remembering them – the round numbers – in public, but more often it happens to me privately, in the solitude of my life as a reader, and I usually use those round numbers as a secret pretext to return to the books, as if I feared that leaving them unattended for too long would make me dislike them. And of course, then accidents happen: one opens The process of Kafka in a moment of distraction or inattention, simply because someone in some newspaper has remembered his centenary death, and hours later he is still there, immersed in the novel, reading it from one cover to the other and confirming, once again, the mystery of That books change so much over time.

Today, June 16, I think about one of those round numbers. Well, 120 years ago, at 8 in the morning, a day began that for many of us has not yet ended, or that continues to happen (or we continue to live it) without there seeming to be a remedy. On June 16, 1904, a writer was not born, nor did he die, nor was a book published, but rather some fictional characters moved within a city made arduously of words. That was the date that James Joyce chose for the action of the Ulises, and all its readers know, and many of those who are not its readers know, that fiction day has become a kind of secular, recreational and literary holiday in Dublin. In that strange city – where one can have the impression, if one is careful, that something wonderful has been written on every corner – people have breakfast with roasted kidneys, like Leopold Bloom, and visit the pharmacy where Bloom bought soap, and the library where Stephen Dedalus spoke with the librarian about Hamlet and Shakespeare. And one suspects that the vast majority of passersby have not read this hermetic and extremely entertaining novel at the same time, but that does not prevent them, of course, from taking part in the routine of fiction: just as it is not necessary to have read Lucas or Mateo to go out to see the Holy Week processions.

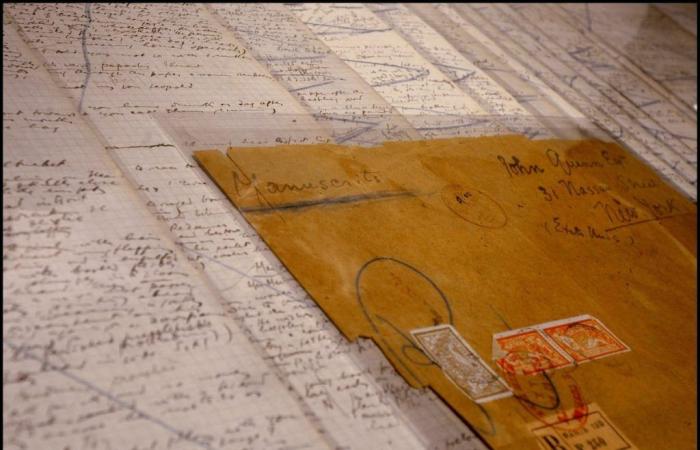

As is known, Joyce chose the date of the action for very precise reasons: June 16, 1904 was the day of his first romantic date with Nora Barnacle, who would become his companion for the rest of his life (and who, famously, he never wanted to read the Ulises). There are traits of Nora in Molly Bloom, that very powerful character who would not receive the approval of our puritan and censorious world today: the novel ends with a fifty-page monologue that is both moving and obscene, and where there are frankly pornographic lines. . He Ulises It encountered resistance from defenders of moral purity long before it was a book, when passages or chapters appeared in various magazines. The story of its publication in the United States is, in itself, one of the great episodes of that saga that does not end: the fight of literature against stupidity. To the Ulises They wanted to ban it because it was obscene, because it was immoral, because it was dangerous, and I have no doubt that it is all that and much more. And it’s scary to think what would have happened if it had fallen into the hands of Ron DeSantis’ Florida, for example, or in certain Vox town halls.

That’s how it is. Apart from his modernist fireworks, the reason for his early notoriety was the impudence with which Ulises It gave us access to territories of the human mind that no one had explored until then. Kundera said that Joyce installed a microphone in the minds of his characters, and what is heard thanks to that microphone is part of the most shameful corners of our psyche, what we would never voluntarily reveal, the most unspeakable and dark. These spies on our human condition take place throughout the novel, but two scenes scandalized the mortal champions more than the others: in one, Leopold Bloom has lustful thoughts while observing a teenager from afar; the other is the final monologue where Molly Bloom, a woman, takes charge of her body and her desire in a way that was at least uncomfortable for many. “Yes, I do,” the last words of the novel, are a cipher of her insolent freedom, and they were more insolent when they were published than later. Now they have been again, because our societies are the most puritanical, reactionary, censorious and punitive that we have seen since the appearance of the Ulises in 1922.

There is a photo of Marilyn Monroe on which rivers of ink have been written and gigs of nonsense have been said. She appears in a bathing suit, sitting on a kind of carousel or wheel, absorbed in a copy of the Ulises. The most uninformed believe that the photo is a montage, even though photographer Eve Arnold has told at least once what happened that day: the trip to Long Island to visit a poet friend, the day at the beach, the moment of intimacy that Marilyn Monroe would only have allowed herself with a trusted person like Arnold. What I like most about the photo is that the book is open to its last pages: Monroe is evidently reading Molly’s monologue. It is not confirmed that she read the entire novel, but it is true that she liked to open it anywhere and read passages aloud, to savor them, and I have always agreed that the Ulises It is a book to read aloud; and, if I had to pick a passage for Marilyn Monroe to read aloud, it would have to be Molly’s monologue.

Today many, not only in Dublin, but throughout the world, will perhaps read the Ulises, and perhaps they will do it out loud. Some of us will do it in Madrid. We will somehow fall into the vain celebration of round numbers. But you will agree, I suppose, that a great novel can have worse fates.

Newsletter

The analysis of current events and the best stories from Colombia, every week in your mailbox

RECEIVE THE

Subscribe here to the EL PAÍS newsletter about Colombia and here to the channel on WhatsAppand receive all the information keys on current events in the country.