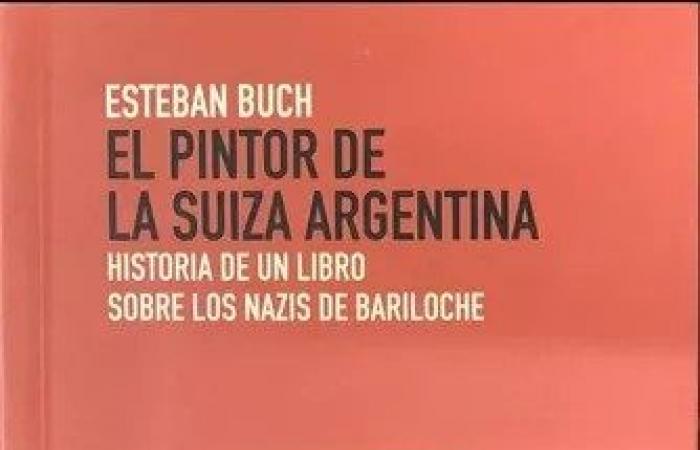

33 years have passed since the publication of “The Painter of Argentine Switzerland”, the book by the musicologist and writer Esteban Buch that tells the life and work of Toon Maes, that “artist” who, after participating in the leadership of the Nazi domination of his country he settled in Bariloche until his death. More than three decades have passed, but the story he told is still valid. So much so that the book will be republished with a review by the author, who will travel from France, where he lives, to present it next Saturday in Bariloche.

Originally published by Sudamericana in 1991, the book about Maes revealed the participation of former SS captain Erich Priebke in the Ardreatine Graves shooting, where 335 civilians were murdered in retaliation for an attack by the Resistance against the German occupation.

“The Painter of Argentine Switzerland” was the spearhead not only of a process of review of the social insertion of the leaders of the Nazi regime in Bariloche but also served so that, three years later, the North American network ABC presented a report that derived at the Priebke world exhibition, and his subsequent arrest.

This recognition to Buch, who is also a professor at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales in Paris, tIt took 18 to arrive. Both Sam Donaldson, the protagonist of the report, and the American news channel, minimized for almost two decades that the basis of his investigation had been precisely Buch’s book.

It was the Canadian miniseries “Nazi Hunters” that settled that debt. In its chapter dedicated to the Priebke case, the ABC team recognizes that “The Painter of Argentine Switzerland” was used as a trigger for the investigation.

As soon as he heard that news, which went around the world, Esteban Buch thought about the offer of information he had made to the Wiesenthal Center without generating interest. “In reality, I clearly measured the distance between a job that is done locally and what a large North American television network can do,” Buch said at that time to the newspaper RÍO NEGRO, on one of his visits to Bariloche.

The difference between being in the center and the periphery. Following the ABC report, Priebke was extradited to Italy and sentenced to life imprisonment in 1998 for the Ardreatine Graves massacre.

When it was published, in 1991, Priebke enjoyed a privileged place in Bariloche society, including as director of the German Argentine Bariloche Cultural Institute, and the Primo Capraro Institute.

“The same atmosphere of impunity gave Priebke peace of mind, not only to continue with his life as a “good neighbor” but even to say that “the idea (of Nazism) was good” even if “the end was terrible.” a phrase he uttered in that same interview. He perhaps believed that saying that about the terrible end was showing signs of a critical spirit, but in reality it was nothing more than the speech of a convinced Nazi, lamenting the defeat. Furthermore, his arrogance reflected his social status, that of a leader accustomed to being treated with respect and honors by military and civil governments,” Buch said in a report with “El extreme Sur de la Patagonia,” in the year 2022.

The book had an extensive journey and became the most emblematic in the history of Bariloche journalism.

Now, the book is republished by Bajo la luna publishing house, and includes a first part in which Buch reviews the research he carried out in Bariloche prior to the publication and the subsequent journey of “The painter:…”

The review of Toon Maes’s life is a way to understand a collective moral wound: how the fugitive Nazi could transform himself into “a notorious Bariloche native,” an artist recognized and appreciated by his fellow citizens.

The new book

The reissue of the book is much more than that. It is titled “History of a book about the Nazis of Bariloche”, Buch reflects on his research and mixes a personal review, a dialogue with the author he was then, journalistic experience. At the same time, it establishes the chain of situations that led to that book being an essential piece in the revelation of Priebke’s whereabouts.

Esteban Buch was born on July 330, 1963 and became a specialist in the relationships between music and politics in the 20th century. Among his books, written alternately in Spanish and French, are “Music, dictatorship, resistance” (Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2016), “La marchita, el escudo y el bombo” (with Ezequiel Adamovsky, Planeta, 2016), “ “Or let us swear with glory to die” (1994, 2nd ed. Eterna Cadencia, 2013), “The Schönberg case” (FCE, 2010), “History of a secret” (Interzona, 2008), “The Bomarzo Affair” (Adriana Hidalgo, 2003), “Beethoven’s Ninth” (Acantilado, 2001) and “The Painter of Argentine Switzerland” (Sudamericana, 1991). He is also the author of opera librettos, for Richter by Mario Lorenzo (2003) and Aliados by Sebastián Rivas (2013). He was a Guggenheim Foundation Fellow, won the Prix des Muses in 1999 and 2007, the Konex Prize 2009, as well as being a professor at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales (EHESS) in Paris.

“I interviewed Priebke”

As the sources say at the end of the bookI interviewed Priebke on September 12, 1989 in the library of the Deutsche Schule Bariloche – Instituto Primo Capraro, the school of the German-Argentine Cultural Association of which he was president for years, while continuing to tend his specialty deli German. I have preserved the recording, made with the small cassette recorder that I usually used in my work as a journalist. It is a document that is published here for the first time, at the end of this volume. The interview had two parts, a formal one, in which Priebke told me about the Germans of Bariloche and said that “the idea [del nazismo] Maybe it was good, but the ending was terrible”, expressing in passing his enthusiasm for the upcoming reunification of Germany; and an informal one, when before saying goodbye, and undoubtedly believing that the recorder was off, he spontaneously began to talk to me about his performance during the war. I transcribe that last part of the conversation, respecting his way of speaking in Spanish, with a strong German accent and many grammatical errors:

– We had a case in Rome, but nothing with Jews, and… the communists had… that is… a bomb, a big bomb, and thirty-two, thirty-three soldiers died immediately, so there was an act of retaliation, but completely legal in the annals of war, but among other things they did not… they had asked the people who carried out the attack to show up and naturally they did not show up as communists, and after the war they were the heroes, it was their fault that they died Three hundred Italians, no, because one to ten were shot for each soldier. There is a famous movie, Massacre in Rome, about this. But the entire command was cleared about this thing because it was a…

– You. Was he tried for that matter?

– No, not me, no, no. Our commander [Herbert Kappler] was in it, but it was completely legal.

TOYes, in 1989, and in fact until the end of his life, Priebke attributed “the blame” for the massacre committed in the caves of the Ardeatine Trenches to the partisans who had attacked the German occupation troops on the Via Rasella, and not the Nazis responsible for the war crime that was the act of retaliation against civilians ordered by Hitler. However, he knew very well that those three hundred and thirty-five murders were committed before the Germans announced the retaliation, so that the perpetrators of the attack could not have prevented them in any way, if they had wanted to. He also denied the former SS the anti-Semitic dimension of his crime, despite the high proportion of Jews included among the victims, as a result of their presence in Roman prisons after successive persecutions by the Italian government and the German occupation troops.

(…)

I will never know why in 1989 Priebke made that confession to me. Sometimes I think that he was the vanity of having been the protagonist of an event worthy of a Hollywood movie with famous actors. Sometimes I imagine that he expressed in this way, as if in a slip of the tongue, an unconscious feeling of guilt, of which to tell the truth no trace will ever be found in what he will later say before judges or journalists. It is more likely that he let himself be carried away by the feeling of impunity that forty years of living peacefully in Argentina had given him, at a historical moment when, after the Full Stop and Due Obedience laws, it seemed that the crimes of the dictatorship Argentina would also remain largely unpunished. During our conversation, he may have felt that telling the truth gave some credence to the lies about his and his comrades’ past that he had told me in the previous forty minutes. Of course, in the interview his confession also arises from a lie, when he spoke of a reprisal that was “completely legal in the annals of war.” In any case, from his point of view he was sure it was a mistake, which three years later was going to deprive him of his freedom for the last nineteen years of his life.

(Extract from the book History of a book about the Nazis of Bariloche”, Editorial Bajolaluna)

The presentation in Bariloche

The presentation of the book “History of a book about the Nazis of Bariloche” (Editorial Bajolaluna), will take place next Saturday, June 22 at 6 p.m.in the Aula Magna of the Bariloche Regional University Center (CRUB) of the National University of Comahue, Quintral 1250.