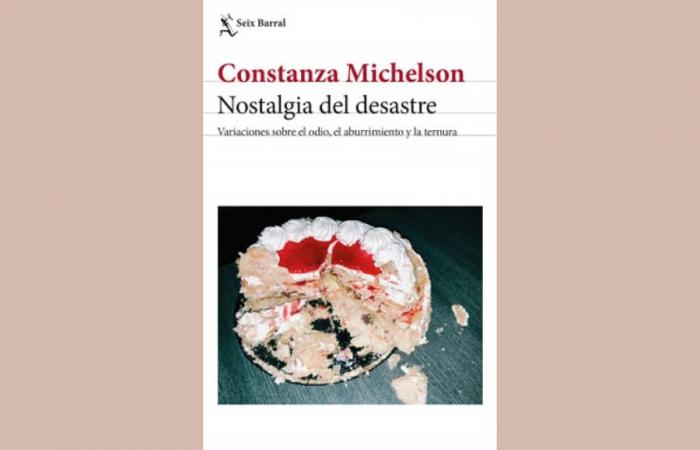

Commentary on the essay Nostalgia for the disaster. Variations on hate, boredom and tendernessby Constanza Michelson (Seix Barral, 2024).*

I. RITES WITHOUT MYTHS

ANDIn the last line of the first page of Constanza Michelson’s book, we read: «Things continue to go; yes, forgetting its meaning. It is a statement about the current state of the world that completely sets the tone of the book, as well as a nostalgic observation, since it can only be made by someone who knew that meaning that is now lost. If, among other things, nostalgia implies a problem, a present discomfort for what is missing, it is only for those of us who manage to have a relationship with that past and, therefore, it is something that will surely disappear with us. Those who did not know what happened before, nor have they had any contact with it, cannot miss anything; but neither does it recognize the ersatz nature of what is present.

What are those things that continue to march, but have forgotten their meaning? Well, almost everything: politics, sex, education, history, for now. They are rites that have been stripped of their myth. But at this point, before heading towards a “retrotopic” drift of nostalgia (Bauman), a question should be inserted: the perception of those things that continue to march, but without their meaning, will not be the first impression that what is made on us? new, or, rather, the unpublished?

And, paradoxically, we “in spite of everything, moderns” have had problems grasping the novelty; because although being modern was being receptive—and even productive—of the new, we preferably located it in a dimension that we call the future, and then we did everything to make it predictable. That is what, for example, the golden age of the Philosophies of History was about: the future as a realization of the moral progress of humanity, of a cosmopolitan right, of more perfect forms of State and freedom, or magnitudes of wealth that would fill , finally, to everyone (to point out three modern paradigms: Kant, Hegel and Hume, respectively). But it seems that today is different, and we are no longer confronted with that type of novelty, but with something that would be better referred to as “the unpublished”, which is largely divorced from the future: what we experience today is more like contact with another world than with future novelty.

It is to this that Constanza Michelson’s reflection applies at least since her two previous books (Until it’s worth living and make the night). He has decided to explore our times without giving in to the clichés of noble causes, not because there are not some just causes, but because the best commitment to them is that of someone who prevents us from being too sure of what we think and what we should do. This is, by definition, an anti-political stance; that is, closed to contingency, crossroads and opportunity.

II. NOSTALGIES

Although we can always suffer for what is lost, the particular configuration that this acquires in nostalgia is a truly modern experience; In fact, the concept was only coined in 1688 by the Swiss doctor Johannes Hofer, and although it initially designated the illness of soldiers who missed their homeland, the subsequent development of the concept—until it reached moral and literary heights in the 19th century—fits point by point with the modern experience par excellence: the revolution as a rupture between past and present, and the development of the doctrine of progress.

In this book, the author points out to us, very close to Steiner and Dostoevsky, another articulation of nostalgia, one that accompanies the end of modernity itself: the “nostalgia of disaster”, the fascination of a generation with the horrors experienced by their predecessors. This is typical of an era of emptiness and boredom, where things are supposed to work too—or suspiciously—well. Paradigm of this would be that State anchored in the nineteenth-century myth of European civilization and progress, which was the fallow ground in which the ferocious monsters that emerged during the first half of the twentieth century were incubated. Between the nostalgia of the disaster and the death drive there is a close relationship, in which it is scary to continue scrutinizing.

That was the spleen, typical of the 19th century, which, like so many things from the end of that era, prefigured those from the beginning of the 21st. It is about something similar, but different: if the 19th century boredom reached the bourgeoisie more; Today’s boredom extends by standardizing classes and any differences. And if the one before came from a boredom with civilization and so much rationality, the one today comes from the post-emancipatory state of all that.

Unlike that ancient boredom, today’s boredom no longer has the trust in humanity to get something going (to “authorize itself to guide history,” writes Michelson), because today humanity is bored with itself. It is not strange that today is no longer a time for political projects, but for “outbursts”, which may be the best political figure in the world. presenteeism as far as the masses are concerned; that is, abdication or inability to produce the future. “Power without power” someone said. At the level of the individual subject, it is the figure of the “political operator” that steals the place of the statesman, that character of whom it was expected historical consciousness: the balance of what you have or don’t have “to transform dreams into plans” (Berman). The trader, on the other hand, improvises and reacts, balances Chinese dishes and speculates, in the stock market sense of the word.

III. REHEARSE LIFE

Referring to the structuring writing of this book as a biographical story may lead to a misunderstanding. Well, it is a story that is not literal, linear or obvious: the “plausible life” will not be found here, since it is, above all, the honest story of someone who assumes what time and its attacks on the subject of yesterday have done. That girl she was, referred to in the third person, is not a mere stylistic choice, but the confession of a self as another. And, in reality, no one is given any other alternative. What happens is that we function better in the belief that we are the same from beginning to end – as if we had the possibility of being consistent – to the point of exalting the consequence as supreme value. It is the remnant of an ancient, spherical concept of truth.

Hence the subterranean question that runs through this book: what happens when things should fail, but finally don’t? Neither providence nor chance operates, but freedom: “The act is mastered at the crossroads,” maintains Michelson. Meaning is constructed when we do something with our determinants and transform them into motives.

Freedom, is it too big a word for our times? Freedom is no longer what we have to give direction to the future of humanity, that was the modern humanist delirium. But humanism does not have to be a delusion. Forced to moderation, we could now speak of a “weak” humanism, without a single, ultimate, normative foundation and prevented from reason-domain (Vattimo): human freedom is nothing but what we can do with our lives, and, by extension, with that of those who are part of them, with a result that is never assured. The only thing that is certain is that we will have to take charge of what results. Responsibility turns out to be the verification of freedom.

And so as Freud pointed out when referring to the mechanism of humanization of uncontrollable natural forces: «We will feel calmer in the midst of the disturbing and we will be able to psychically elaborate our anguish. We continue perhaps helpless, but we no longer feel paralyzed.

This text is an excerpt from the presentation of the book held by the author in Valparaíso, on June 7.