Despite having lost a leg in an accident when he was young, he carried out his duties as a Copec firefighter with a crutch on his back, without caring about anything (Óscar Aleuy)

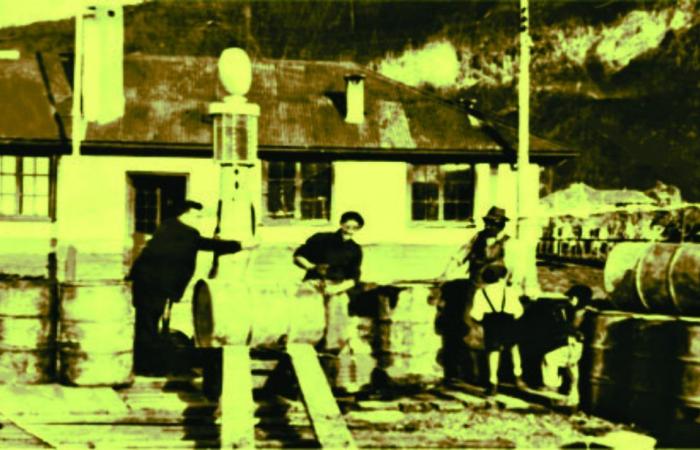

By 1936 the appearance of Puerto Aysén was flat and flattened. There was no good walking due to the threat of new showers and you had to take care of yourself, as Aunt Encarnación’s seamstresses used to say. Everywhere you saw a building, preferably one story and of low density, although there were larger constructions that broke the monotony of the complex. The idea from the beginning was to build 2 and 3-story houses plus some warehouses that completed the town. The highest constructions predominated, which could be exclusively a dwelling house or a combination of a warehouse below and a room above. There was a lot of trade! The few hotels were larger buildings and almost all wooden constructions and some lined with zinc, a material that was generally used for roofing.

Some characteristics of the port

In 1936, Puerto Aysén could not yet pretend to be more than a town. Some disowned him, but others always loved him. That same year, around 330 houses were counted that, although they covered almost the entire urban plan, did not form a very dense conglomerate, revealing evident progress with respect to the swamp that in 1928 was centered on the SIA facilities.

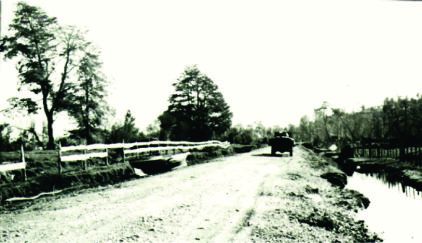

Its streets could hardly be called such and its sidewalks even less so. His untidiness was characteristic. The most orderly and particular thing about the port was commerce and public service.

The arrival of Don Vicente to the radio

I want to focus on this description because today I receive treasured testimonial memories from people who knew those times and whose words left me reflecting for many years. Today I once again remember the thousands of interviewees that I heard and with a lump in my throat I once again have them by my side just as they came to me.

One winter afternoon he crossed the radio door Santa María La ViejaDon Vicente Muñoz Ballesteros, the first Copec worker from Puerto Aysén and Coyhaique, at a time when I was on Thursday recording and testing for the edition of the great program Those Who Came First. Vicente was old now and waited for me to leave the room. He was accompanied by two relatives who helped him get up to meet us in the doorway and sit down to talk. When we finished, an hour later, my head was already full of his impressions and thousands of facts that until then I was completely unaware of.

Night had fallen and Vicente was there, still and silent, almost excited and waiting patiently for my arrival. Someone who remained next to him would tell me days later that none of the three spoke a single word. My new friend Vicente said and expressed it all, through a long spasm of data accumulated for years. It seems that he had proposed it as an imposition.

Time has been responsible for highlighting and accentuating the image of this good man, a worker of principles in the middle of a too wide Chile Argentina street in the main port and at that time the capital of the territory. I say this because as those years progressed, the compilation work grew and took on valuable dimensions.

I didn’t know who this man was, until someone slipped me a letter where I read that the family had wanted to write to the Sunday production to see if he would appear on the famous program. That radio afternoon, Don Vicente appeared in person and I hugged him as gently as possible, meeting his calloused, wrinkled hands. I barely heard him tell me that it was very nice to hear me on Sundays and that he would like to speak there with his voice, although there were some who appeared and were not so pioneers since they They had arrived long after me.

He moved through life on crutches, having had a nasty accident with a saw that tore off a calf. According to a chronicler of the time, this noted gasoline dispatcher worked a whopping 9,125 days without missing work once. This is equivalent to around one hundred thousand work hours. Today, that is not news like it was before.

The first movements of the gasoline pumps

It was in 1927 that the first liters of gasoline began to be shipped as a product for sale in the province of Aysén. The only tanks available consisted of very special spouts that are only seen in old photos, which had a hexagonal structure, were tall and narrow, and were always covered by a round sphere at the top. There were several. On Chile Argentina Street, for example, you could see two and also one on Baquedano Street which, according to what I have been told, was installed and exploited by the Italian pioneer Saturnino Galilea and another by the also Italian Antonio Molettieri. It was precisely that year that the first motorized vehicles appeared that occupied the few narrow gauge roads between the ranches, especially the section that ran from the Administration of the Agricultural School to Sitio El Zorro, Coyhaique Alto, Punta El Monte route and Ñirehuao until connecting with El Balseo. Before that, vehicles circulated on those bad ranch roads and very few had fuel, which was brought from Argentine towns to supply themselves. As there were few transporters, they, the privileged José Calvo and Chepo Muñoz, supplied the truckers.

The commercial circulation of vehicles was carried out on the roads and paths that linked various points of the territory. The main road was the one that linked Puerto Aysén with Baquedano and Valle Simpson, even reaching Balmaceda and the borders.

The first days of the new Copec dispatcher

When Copec was installed in the port it was a celebration, since the few truckers at that time knew that they would not have to go to Argentina to get it. There they saw for the first time a young man with crutches who called himself Vicente. He earned a salary of 180 pesos and was affable and welcoming to the exclusive Aysenino clients. The first agent for the area of the Chilean Petroleum Company was there, he worked and was a representative of the firm for Aysén. His name was Luis de la Quintana. But the one who really helped, encouraged and advised the new worker Muñoz was Francisco Pancho Quezada, one of the most emblematic truck drivers of the first Aysen routes. Thanks to him, thanks to his efforts and the strength of his convictions, the Copec agency was able to reach this area. Not only did he provide the deposit that was needed for the procedure (a kind of guarantee check), but he also staunchly defended this alternative, giving proof of guarantee for total security for the task. Later, Fidel Henríquez Cornish, Roberto Cárdenas and Ramón Fernández Diez passed through Copec as agents.

Initially, gasoline was sold in 18-liter gallons. They were the gasoline cans. A liter cost 85 cents and the small storage tanks that remained in a commercial establishment that was right at the point of sale were always full of cans, at a time when security levels were quite precarious.

In July 1962, fair recognition was given to this lifelong worker, whose retirement occurred in the 1980s. He himself chose the day to be honored, and the award and encouragement he would receive from the Municipality, he deliver Don Pedro Schultteis, the first driver who made the Coyhaique-Aysén route. At that time Don Pedro had already died, and Muñoz did not know it, so the honor of representing him was assigned to his bosom friend Pancho Quezada, another of the famous truck drivers of the time.

Sometimes these human figures that populated the beginnings of the territory are outstanding. His actions completely escape normality. This is the case of Muñoz Ballesteros, whose work life was closely linked to the difficult job of attending to the gas pumps without missing a single day from work.

These historic beginnings found a thorough man, dedicated entirely to the function entrusted to him by his patron, Don Ramón Fernández Diez. They were the new steps in a different time than the first pump that operated on Moraleda Street, and this one, which was the second, was located in the middle of Baquedano Street where hundreds of vehicles completed the obligatory section towards the port under the popular premise of today we go down to Aysén.

The last relic

We have recognized one of these gas stations, which is displayed in a location on Bilbao Street, as a true relic, fulfilling meritorious functions in the era when they were most useful and which today is valued from the point of view of a nostalgic work artifact.

The only truly surprising detail is that Don Vicente was missing a leg and despite this, he attacked with recognized enthusiasm to ensure that this limitation did not prevent him from fulfilling his dream. He always knew how to compensate for his condition with enthusiasm and true devotion and did not care at all, despite the hard work in the midst of an awakening to new times, in which Coyhaique and Puerto Aysén opened the doors to other stages.

We are located in 1937. The main road opening in Farellón had been completed a few years ago and was already operable for very few vehicles that began to arrive and work through the most inhospitable lands of Patagonia. These trucks, vans and cars had begun to increase their traffic movements, and they had to fill tanks at the Copec pump where Don Vicente, with the parsimony that his physical defect demanded, fulfilled the orders with very special diligence, covering the orders of an impeccable form, resigned to his limitation that would accompany him throughout his life.

The same gasoline pump that is displayed at the entrance of the Belisario Jara Hostel as a relic is the one used by men like Don Vicente. If you approach it, imagine those times, close your eyes and meditate. Something will go through your mind when you conjure truck engines grumbling between the low winter temperatures, the smell of fuel, total darkness and perhaps some confrontation with fear on those impossible trips.

Perhaps you imagine a man advancing from the shadows, limping with difficulty to carry the ponds again and again. That good man is still Don Vicente Muñoz Ballesteros.

If you are interested in receiving news published in Diario Regional Aysén, register your email here

If you are going to use content from our newspaper (texts or simply data) in any media, blog or Social Networks, indicate the source, otherwise you will be incurring a crime sanctioned by Law No. 17,336, on Intellectual Property. The above does not apply to photographs and videos, since their reproduction for informational purposes is totally PROHIBITED.