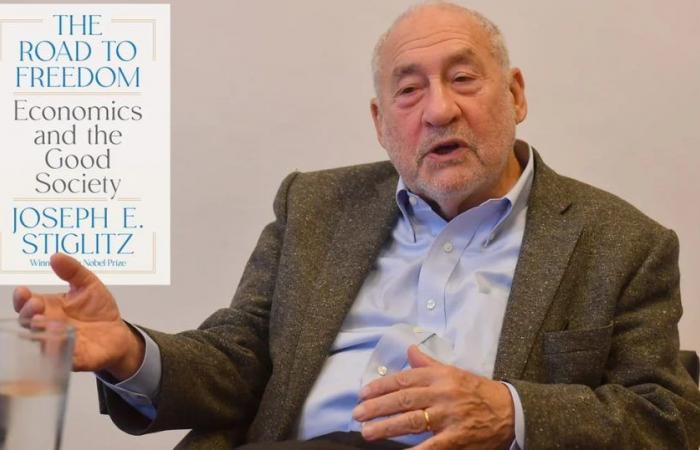

Joseph Stiglitz He has been for decades the most eminent economist in the world. His pioneering work on information asymmetries in markets earned him the joint award of the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2001. He chaired Bill Clinton’s Council of Economic Advisers, was chief economist of the World Bank and led the report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2007. He has written more than 10 books aimed at a general audience, including the best-seller Globalization and its discontents. Stiglitz’s career not only resembles that of great 20th century economists such as John Maynard Keynes and Milton Friedman, but in some ways surpasses it.

In his new book, Another form of freedom: The economy and the good societyStiglitz positions himself firmly on the side of Keynes, advocating greater state intervention to generate economic prosperity and offering a reply to conservative works such as Capitalism and freedom (1962) by Friedman, which defined a generation, and the classic by FA Hayek easement road (1944). Stiglitz wants to rescue the very idea of freedom from the “superficial, mistaken and ideologically motivated” version that “the right” promotes. The book presents a coherent narrative and argument: Using a flawed definition of freedom, which privileges a largely unregulated market over other social goods, neoliberal capitalism – or “unfettered capitalism” – has meant “liberating financial markets to precipitating the biggest financial crisis in three quarters of a century; free trade to accelerate deindustrialization; and freeing companies to exploit consumers, workers and the environment alike. With an argument reminiscent of Karl Polanyi, who claimed that unbridled capitalism creates reactionary politics in a “double movement,” Stiglitz asserts that the “crimes” of neoliberalism have increased inequality, weakened democracy, and provoked a populist backlash throughout the world.

To remedy this, he advocates a progressive capitalism, one that uses a different definition of freedom, one with “inherent links to notions of equity, justice and well-being.” The concept of compensation, common currency in economics, occupies a central place in his arguments. Stiglitz argues that freedom is always limited in one way or another, and that we should pay less attention to individual freedom and more to the “set of opportunities” that society as a whole makes available to the less fortunate. To expand the opportunities of some, we must reduce those of others.

This is both a pragmatic argument – that our society has made wrong trade-offs and we are all worse for it – and an ethical one, in the sense that Stiglitz believes current conditions are deeply immoral. For example, considering the decline in wages for American workers amid globalization, he asks, somewhat hyperbolically, “Is there much difference between the current situation and what happened in South Africa, where people were forced to work in the mines because they were prohibited from working on the land? In another passage, he writes that “the call for a return to liberalism under the new name of neoliberalism” was “akin to Hitler’s Big Lie.” What would progressive capitalism be like? “Something along the lines of a rejuvenated European social democracy” or “a 21st century version of social democracy or the Scandinavian welfare state.”

Readers of Stiglitz’s earlier work may be familiar with his arguments for progressive capitalism, but they won’t find much economics in this text, which delves deeper into philosophical territory. This is not Stiglitz’s strong point. It is sharpest when he debunks economic fables, such as the Chicago School’s claim that monopolies will always attract competition, or when he criticizes the excesses of post-Cold War globalization, such as the eager selling of dubious Argentine bonds. . Stiglitz excels at fighting fire with fire.

Their ethical arguments do not have the same force. One of the reasons is that it remains within what the social psychologist Jonathan Haidt has called the harm/care moral framework that guides modern American liberalism. This makes it difficult for Stiglitz to anticipate, understand, or counter disagreement with his ethical ideas or beliefs, which he simply asserts as self-evident truths. But if inequality is so intrinsically immoral, why is it often tolerated, even by those who are not wealthy? Within the equally powerful moral sensibility of equity/reciprocity, a certain amount of inequality can be interpreted as a fair result of differential effort. Seriously engaging with this perspective would have strengthened Stiglitz’s argument against it. This is not a dynamic unique to Stiglitz, but rather reflects the broader struggle of what the Pew Research Center calls “the progressive left” to connect with Americans who do not believe, for example, that, as Stiglitz writes, “there is little or no moral primacy to be accorded to people’s market incomes.”

So if the book is not written to convince the unconvinced, perhaps it is a manual for knowing your enemy? Stiglitz’s named antagonists are Friedman and Hayek, whose pro-market ideas he deploys superficially to suit polemical ends. He also ignores some of their beliefs. He points out, for example, the International Monetary Fund as a predatory neoliberal institution that spreads exploitation throughout the world, but seems to ignore that Friedman called for the abolition of both that institution and the World Bank. He also does not point out that many Austrian school economists, in the tradition of Hayek, believe that intellectual property—which Stiglitz roundly criticizes for slowing innovation and raising prices—is a fundamentally illegitimate concept. Likewise, Hayek believed that market rents had no moral value, a curious coincidence that is certainly worth considering, given his and Stiglitz’s very different conclusions.

As the book progresses, it becomes clear that its true target is Stiglitz’s own generation of economists. At the outset, he identifies the “right” as various groups that share “the belief that the role of the federal government and collective action should be limited,” a definition so broad as to be meaningless. Over time, however, he begins to use the right as shorthand for “the standard economic perspective.” Although he doesn’t add many nuggets from his time in government to his text, one can sense here the ghosts of Clinton-era battles over economic policy.

By the end of the book, it’s hard to escape the impression that Stiglitz is fighting 1990s battles. Even as he details the deprivations of neoliberalism, he documents its precipitous decline in recent years. The Green New Deal and industrial policy, signs of the evolution of the Democratic Party, appear fleetingly. And he shows little recognition that the economic policy of the Republican Party, or of the right in its Trumpist incarnation, has left market fundamentalism far behind. If we end up with a regime based on closed borders and 100% tariffs, Stiglitz might find himself painfully nostalgic for the crimes of neoliberalism.

Source The Washington Post

[Fotos Maximiliano Luna]