Despite all the attempts that Malba makes to expel you – the indifference of the bar girls is just a preamble to the drama of online shopping that requires the same dedication as reserving a flight, only in the last stage it is tilda–, I managed to enter and tour the tribute to Antonio Berni that the Mondongo duo exhibits in the basement of the museum. ANDI understood catabasis; a light descent like the ramp that takes you into a delicate slum with details cute: cross-stitch pillow, dolls, a miniature rabbit in a pot. To access the manifestation (that of art, since no other will take place), passage through the village experience is mandatory. If we wanted to dialogue with poverty, it would be enough to leave the museum, walk a few blocks and enter Barrio 31, which has been multiplying for decades behind us.

This exhibition proposes another dialogue, almost a script with its perfect storyboard made of vignettes from our history, which the public, as they go through, puts in motion, as if he were filming a movie: the path of the poor in Argentine art. There, under those painted cardboards that could very well be a Pol-ka set, is not Esteban Lamothe playing an irresistible gallant without esses, but rather the reversed protagonists of the first militant painting in Argentine history: Without bread and without work (1894), by Ernesto de la Cárcova.

Mondongo’s sample has four moments. The first, an installation: the interior of a tin house where Argentine families who visit the museum make themselves selfies Like in the ’90s, the Kirchner family and many others took photos with disposable Kodaks at Mickey Mouse’s house in Magic Kingdom.

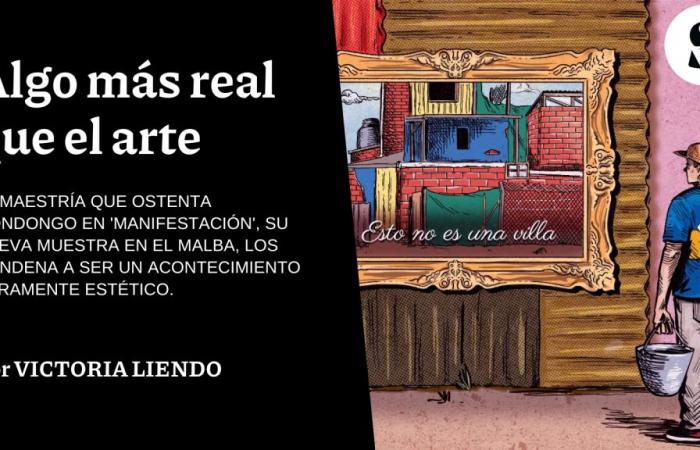

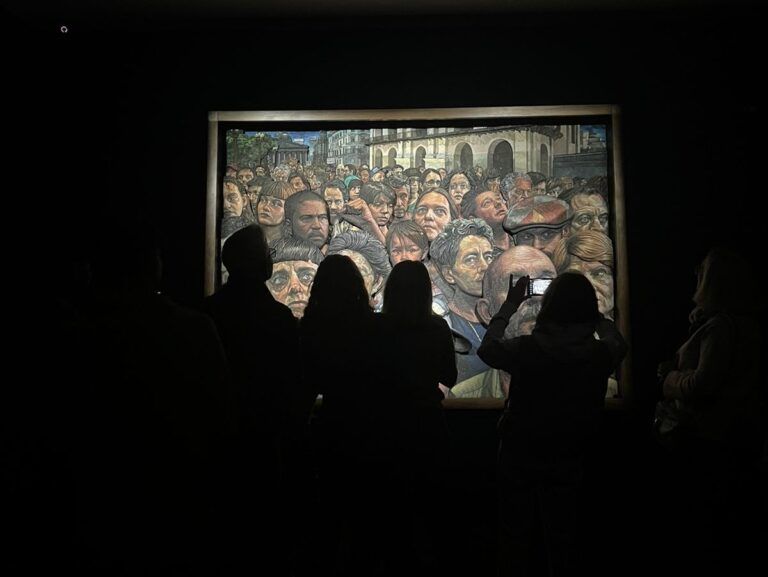

Demonstration (2024), Mondongo.

The second, Berni’s original crowd, desperate for poverty in the early ’30s. The third, a round work like a plasticine Brueghel where children stop to look at the thousands of small scenes of daily life in an Argentine favela (on a bridge, a painting by Perón 1976; in a small street, evangelical echoes with a sign that says: “Igreja Do Nazareno”). Fourth, Manifestation de Mondongo, his tribute to Berni, the first work that the couple sold for six figures. Between the first and the last, other works that in the past made art a disturbing fact enter the conversation.

The artist and the masses

For Ernesto de la Cárcova, whose early success included the sale of a drawing to the king of Italy (Mondongo, for his part, received a commission from the kings of Spain in 2003), looking at the working class was discovering a world. An x-ray showed that in the first sketch (made in Italy) smoke was coming from the factory chimneys seen from the window of this family of three. It was upon arriving in Buenos Aires, in the panic of 1890, that the artist erased the smoke and added the mounted police, a sign of a closed factory and repressed workers. It will be the only painting with a social theme that the painter will make before turning entirely to rural landscapes.

Discovering that that house we enter today in 2024 is where that family hungry for food lives. fin de siècle It is the climax of moment one. What follows will be to go out into the street (indoors) and approach the demonstration that the characters of Without bread and without work They look out the window.

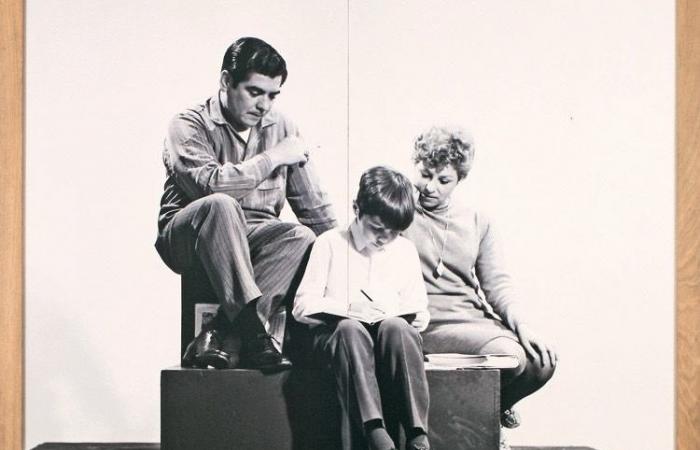

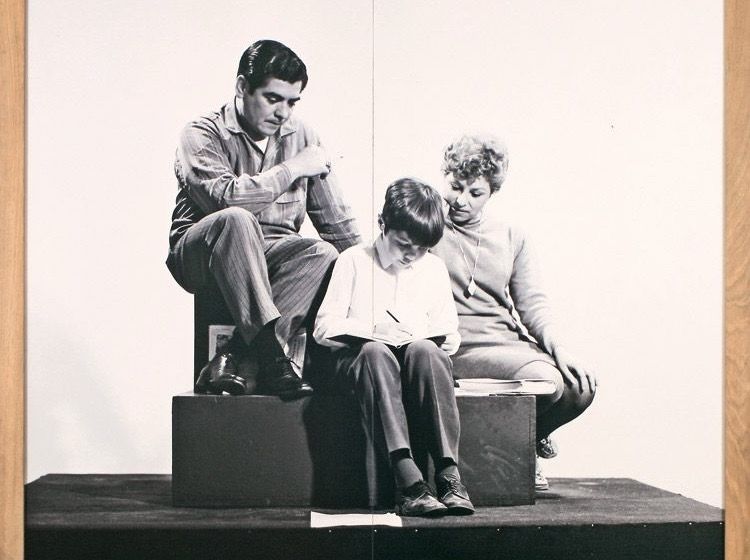

De la Cárcova seen by Mondongo.

Berni & Bony

In the video promoting Malba, the artist Manuel Mendanha, one of Mondongo’s halves, remembers that Berni, when he returned from Paris, his eyes broke from seeing so many poor people. The close-up he forces us into is devastating and tragically sublime. Another artist, a disciple of Rosario, wanted like him to wake up society, and he did.

The working family (1968), between body art and ready-madewas the work that Oscar Bony presented in Experiences 68, the legendary Di Tella exhibition after which the Onganía government closed the institute. On a platform that had a little sign (the little sign was crucial) a father, a mother and a son spent – eating, talking, smoking, reading – eight hours a day, the length of a working day. In black letters it read: “Luis Ricardo Rodríguez, a toolmaker by profession, receives double what he earns in his trade, for remaining on display with his wife and his son during the exhibition.” Can you imagine going to see something like that today? Those who watched the series Fine arts, they will be laughing; the fans of Sex and the City You will remember Carrie’s Big Mac and the “funny” by Aleksandr Petrovsky; lovers of contemporary art will be able to get a taste of name dropping.

Bony’s intention was to confront, to make uncomfortable. He once defined himself as a “torturer,” although making a black man explicit in an insolent manner is more like emotional blackmail than torture. It is true that the family gave their consent to participate, and that the public entered of their own free will, but to exhibit them like animals or as things in exchange for money was to impose a shared humiliation on the spectators. “It’s obvious,” Bony said in the ’90s, “that the work was based on ethics, because exposing them to ridicule made me feel uncomfortable.”

Photo of ‘The working family’ (1968) by Oscar Bony, today at Malba.

What are the power dynamics between the artist, participants and viewers? How many looks were there? They say that the boy would not sit still and ran around the room. I looked for some testimony from spectators who had begun to dialogue with those exhibited, but I found nothing. Shame acted invisible, perhaps, like an electric fence.

By exploiting the Rodriguez family in front of everyone (even paying them double), the artist sought a real, emancipatory impact on the lower classes, but he only managed to increase his fame, bad or good, and become a modest milestone of Argentine art before to change fields and become a rock photographer.

If art does not reach the masses –Oscar Bony said to himself–, let the masses reach art. He might be an exploiter, but at least he was a class-conscious one, who had put a die-maker on display. When the de facto government closes the Di Tella Institute, the artists will take to the streets to burn their works; Luckily, the Rodríguezes were allowed to return home.

The concert of the dams

At the 1972 Venice Biennale, the Italian artist Gino De Dominicis exhibited a young man with Down syndrome. The difference in chromosomes makes the exchange of glances even more brutal than the class difference. The playwright Lola Arias, less daring, joins this tradition with her recent work The days outsidethe theatrical correlate of the documentary Reas: a kind of end-of-prison act in which five women and a trans boy tell us in a musical about their conversion from criminals with a sentence served to actresses with bread and work. Many are excited that art is a place of social struggle; For me, the mere idea that it is my duty to supply the State, the Church and Grabois makes me feel suffocated.

‘The days outside’, by Lola Arias. Photo by Carlos Furman.

People applaud excitedly all the time; A speech ends with the word “conurbano” and an applause sounds in the darkness. I wish each of them, and him, the best, but it is difficult for me to applaud when the luxury of an outstanding technique is missing.

Poor matter and aesthetic luxury

The plasticine technique of the Mondongo duo is the definition of excellence in the arte povera, an Italian trend from the ’60s that advocated the use of cheap materials manipulated to the point of mastery. His exploration of plasticine (from which the term “sculpting” derives) went so far as to invent metal brushes to use as oil paint. That they return again and again with impressive works is a show of strength against those who recognize their commercial success but deny them prestige. A contempt that is difficult to justify: the Orangerie Museum with its water lilies would not be able to overshadow the Entre Ríos landscape exhibited at the Mamba in 2013; Nor could the Versailles hall of mirrors destroy the miniature version that the artists made for a street performance in 2015.

“All artists are equal. “They dream of doing something that is more social, more collaborative and more real than art,” said artist Dan Graham, and the Mondongos seem to say the same thing when referring to their version of Manifestation like “a collective hug.” In her work, the protagonist is not Berni’s unknown crowd, but her own red circle: famous friends, normal friends, daughter, grandmother. There is diversity in age and profession: doctors, writers, film directors, editors, poets and even millionaires take to the streets. But the luxury of the procedure they handle takes away any social discourse. A portal of another order – the aesthetic fact – opens for the enthralled spectator.

Selfies with Berni.

As I leave the exhibition I wonder: if in Berni’s work (as in Bony’s and Cárcova’s), the poor were the protagonists, what place do they have now that the foreground is occupied by a group of friends? cool? What is this new crowd doing in the street? Are you asking for the salaries of those who have it worst or for subsidies and scholarships? Those who saw the beginning of the movie Puan You will know the discussion: is leisure necessary to be able to create? Is inequality the condition sine qua non of art? And don’t those who know how to give it life deserve patrons? While we ask ourselves these questions and people take photos with the town in the background, the poor are left outside, the object of a work that they will not see, which is about them but is for others.